Columbus World War II veteran received letter of recommendation from Oppenheimer

To the world, J. Robert Oppenheimer — the subject of the 2023 Christopher Nolan film — was a gifted physicist, director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory, and the “father of the atomic bomb.”

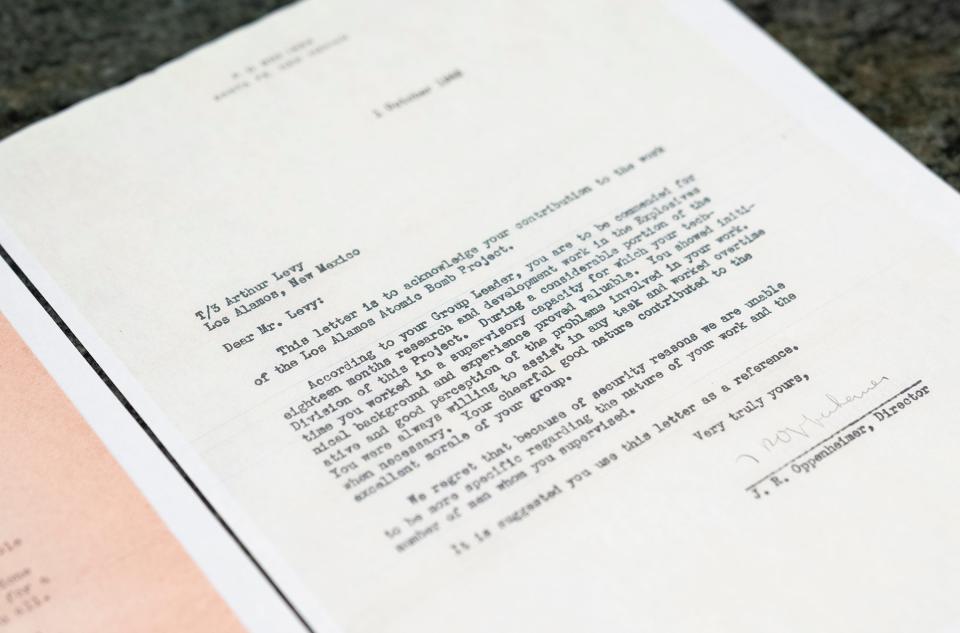

To the late Worthington resident Arthur Levy, he was an employer who wrote a decent letter of recommendation.

“Dear Mr. Levy,” Oppenheimer wrote in a letter dated Oct. 1, 1945, “You showed initiative and good perception of the problems in your work. You were always willing to assist in any task and worked overtime when necessary. Your cheerful good nature contributed to the excellent morale of your group.”

That work was helping to build atomic bombs, which were detonated just two months earlier over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — effectively ending World War II.

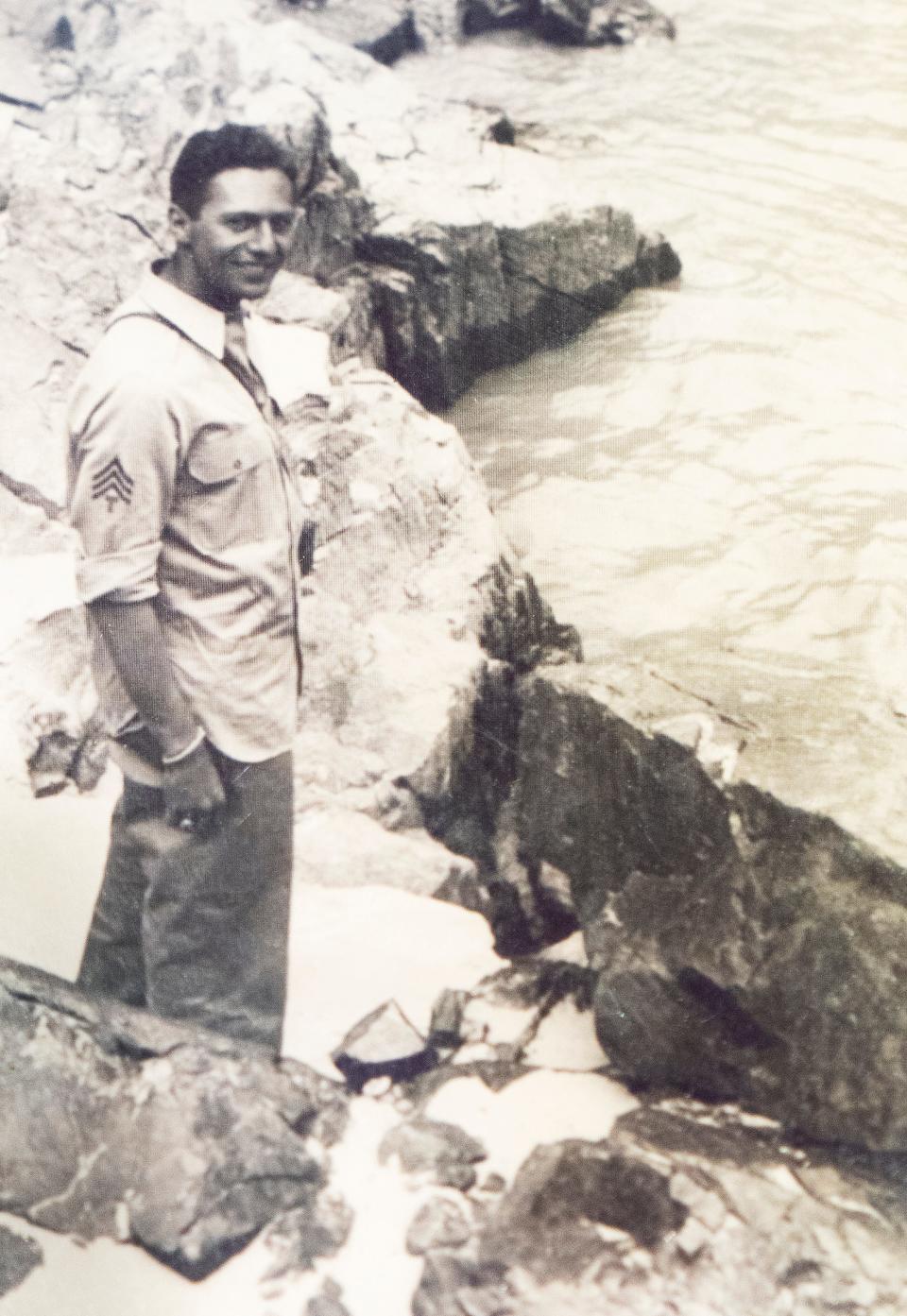

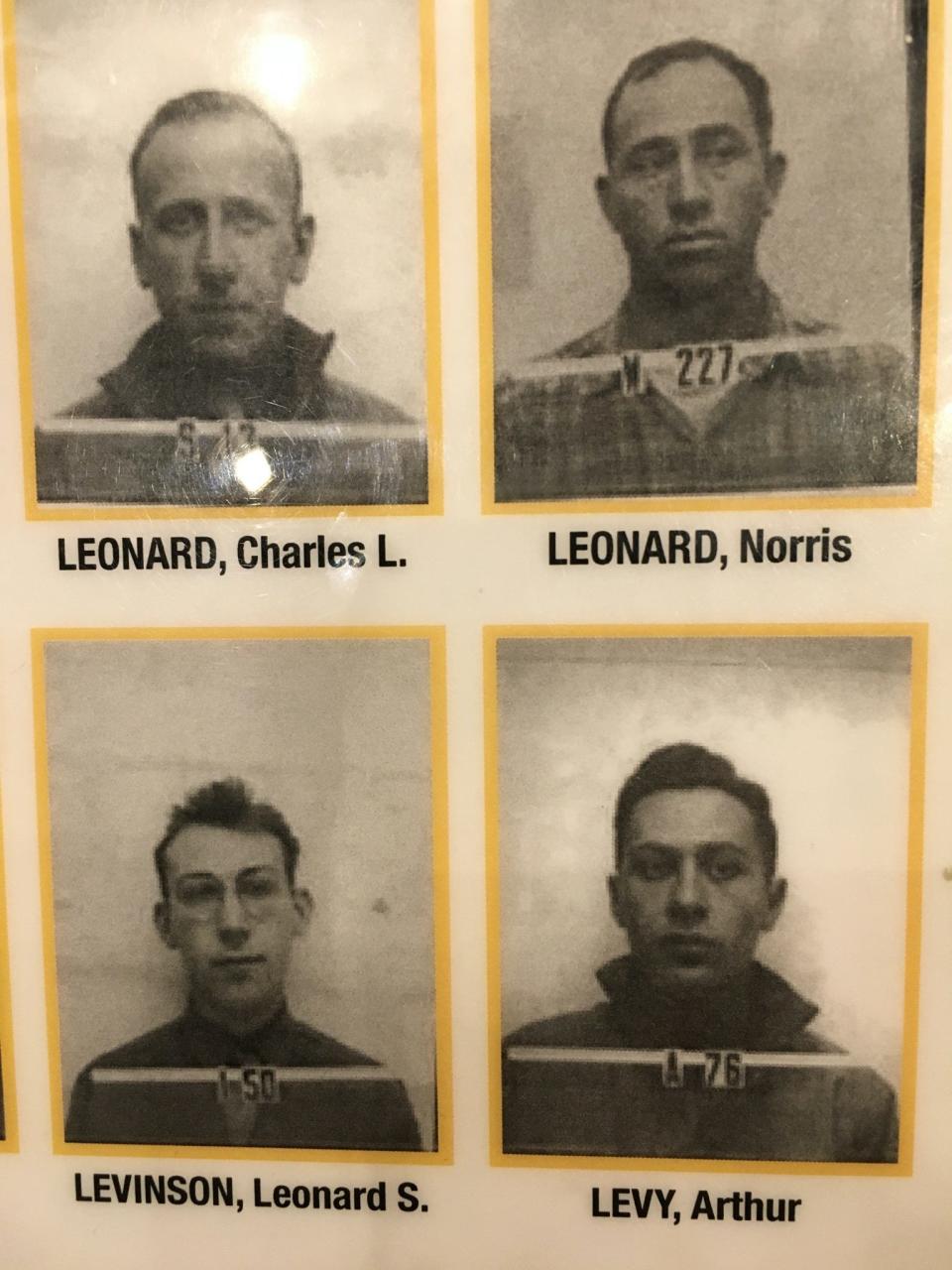

Levy, an Army veteran who would later work for Battelle, spent 18 months in the explosives division of the Manhattan Project.

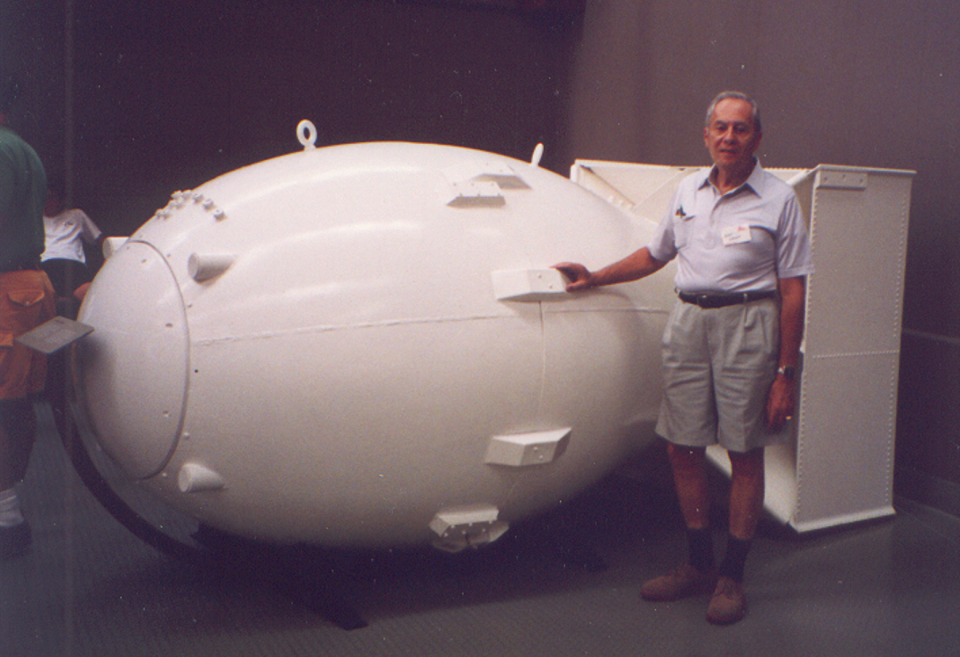

Though modest about his role, Levy talked openly about the initiative, especially as a history lesson for students, according to his four adult children, who have yet to see the “Oppenheimer” film. They describe their father, who died at 96 in 2017, as an engaging teacher and lifelong learner with a “super sense of humor.”

“He was willing to talk to the high schools on Veteran’s Day because he wanted to promote education,” said Rick Levy, 63, of Westerville. “But he was always low-key about it.”

Fact-checking 'Oppenheimer': Was Albert Einstein really a friend? What's true, what isn't

'We had no idea what we were agreeing to'

Born in the Queens borough of New York City in 1921, Arthur Levy grew up in Richmond Hill, New York, and went on to study chemistry at Queens College. After graduating in 1943, he enlisted in the Army, which allowed him to continue his education at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

One day, an officer visited the university and asked Levy and several others if they’d be interested in applying their college training.

“We had no idea what we were agreeing to, but heck it sounded intriguing,” Levy wrote years ago in an email to his daughter, Patty King, 70, of Hilliard, and her husband, Tim, about his experience.

Levy was put on a train to Oak Ridge, Tennessee — one of several Manhattan Project sites — and then on another to Lamy, New Mexico. From there, a bus drove him through Española to Santa Fe, and then on to Los Alamos. It was March 1944. Levy was 22.

“I remember Easter Sunday, it was snowing, maybe 5-6 inches,” Levy wrote. “The sun came out, and before you knew it, the snow disappeared, evaporated!”

Building 'the Gadget'

As seen in the “Oppenheimer” film, the Los Alamos site was a military establishment, which included Army personnel, “college techies” like Levy, scientists and other civilians. Oppenheimer (portrayed by Cillian Murphy) reported to Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves (portrayed by Matt Damon) of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, who directed the Manhattan Project.

Levy also received a letter from Groves thanking him for his "devotion to duty" and "efforts to maintain the vital security of the project."

Levy wrote that he was assigned to a group at “S-Site,” headed up by Ukrainian American professor George Kistiakowsky, a Harvard physical chemist with a strong accent and interest in skiing, who “blew up several trees to make the first ski slope at Los Alamos.”

“I can’t recall how long it was until we knew what we were working on … maybe a few weeks or so,” Levy wrote. “When we found out, we only referred to it as the Gadget.”

More: The explosive history behind 'Oppenheimer'

Levy said he was not fond of working with explosives.

“Here I was with about 10 other scared, young, inexperienced chemists, working in a laboratory,” he wrote. “After we got over our initial fears, it turns out that high explosives like TNT, RDX, etc. are really quite safe to handle. In fact, we would saw and drill explosives.”

Levy was impressed by the notable scientists at the Los Alamos site, many of whom are either portrayed or mentioned in the movie.

“I am reminded of the first time I saw (physicist Enrico Fermi),” he wrote. “I went to a lecture at the Tech Center one evening. This darkish, swarthy guy in a lumberjacket is up there cleaning the blackboards. … He then turns around and starts delivering his lecture.”

Also present at the lectures were Hans Bethe, Oppenheimer, Niels Bohr, Harold Urey, Groves and James B. Conant, Levy said.

Levy recalled working on different nuclear bombs, including the “Fat Man,” which was ultimately dropped on Nagasaki. And he was given a glass paperweight containing soil from the “Trinity” test of the first nuclear weapon detonation in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945 — reenacted in one of the tensest scenes in “Oppenheimer.”

'Those were different times'

The film interrogates Oppenheimer’s guilt about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which killed approximately 200,000 people, and reservations about future use of nuclear weapons.

According to his children, Levy did not express regret about the Manhattan Project.

“The kids often asked him about that,” Patty said of Levy’s talks at local schools. “And he always came back with the number of lives it saved, because it ended the war so much earlier. So, I think he was comfortable with the way things went.”

But that isn't to say he didn't think of the ramifications, said Levy's son, Paul, 67, of Rochester, New York.

“I’m not trying to rationalize it,” he continued. “You sit there and you try and think, what was the mindset of people in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s when there was this arms race? Those were quite different times.”

Following the war, Levy remained in Los Alamos for a brief period, helping to classify records. Then, he received a master’s degree in physical chemistry from the University of Minnesota, where he met his wife, Rita.

In 1951, he moved to central Ohio to begin a 30-year career with applied science and technology organization Battelle, where his work centered around air pollution studies. Following retirement, he worked as a consultant for the Ohio Coal Development Office.

Manhattan Project lectures aside, Levy would also visit schools to conduct chemistry experiments.

“He was Bill Nye before Bill Nye,” Paul said.

And at one point, Levy's kids recorded some of his lectures on a CD for his grandchildren.

“He was a real teacher,” said Mark Levy, 72, of Dayton, Ohio. “His whole delivery is oriented towards the kids.”

Other Columbus connections to the Manhattan Project

Levy wasn’t the only central Ohio resident with connections to the Manhattan Project. The present-day Chromedge Studios in Franklinton was once B&T Metals, a Black-owned aluminum factory that produced about 50 tons of extruded uranium for the Manhattan Project in 1943.

Additionally, U.S. Air Force veteran Paul Tibbets, who lived in Columbus, flew the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Paul Levy said he thinks the interest the "Oppenheimer" movie is inspiring is "neat." He plans to see the film eventually.

“We’ll get there,” he said.

Rick Levy also plans to watch.

“I do want to go,” he said. “I was kind of curious to see, how does the movie present things versus ‘what did Dad say?'"

ethompson@dispatch.com

@miss_ethompson

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Columbus veteran Arthur Levy helped Oppenheimer create atomic bomb