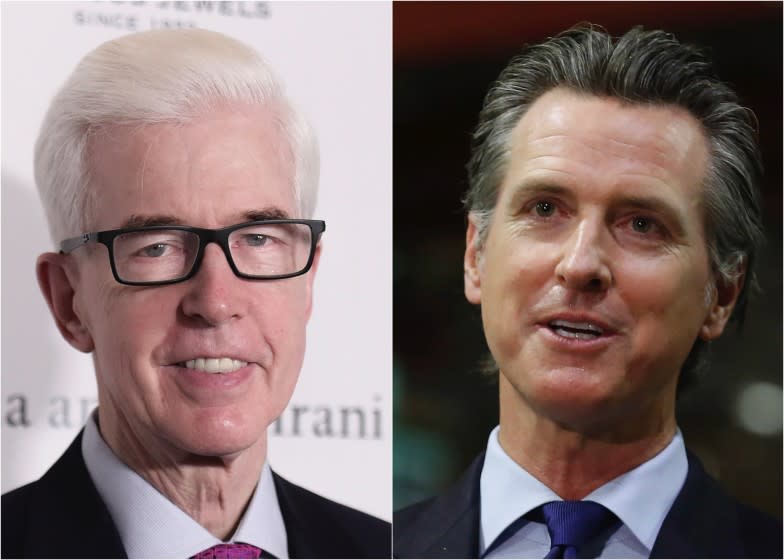

Column: Could Gavin Newsom lose even if he beats the recall?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 2002, running for reelection, California Gov. Gray Davis faced a hapless Republican opponent by the name of Bill Simon Jr.

Simon, a wealthy banker and political neophyte, never stood a chance against the Democratic incumbent. He had the charisma of a turnip, staked positions far afield of most Californians and bumbled through a campaign that was chronically and comically inept.

When election day arrived, however, the results were stunning. After several cliffhanging hours in which the lead traded hands several times, Davis prevailed by a mere 47% to 42%.

The outcome wouldn't have been close if a blowout hadn't been expected.

Which may sound paradoxical, but can be easily explained: Complacency and overconfidence among Democrats almost cost Davis a second term. Ultimately, those factors led to his recall less than a year later.

Gov. Gavin Newsom, as it happens, faces similar peril as he seeks to avoid Davis' fate and keep from becoming the second California governor — and only the third governor nationwide — to be recalled by voters before his term ends.

His greatest problem isn't any of the Republicans he faces. Rather, it's apathy among fellow Democrats, who won't save Newsom's skin if they don't vote. Until recently, a lot of the governor's fellow partisans treated the recall as a joke and certainly no threat in a state where the GOP hasn't won a statewide contest since before Apple sold its first iPhone.

But there's a big difference between beating the attempted recall and crushing it. If Newsom prevails in less-than-impressive fashion, will that weaken him politically if, as widely assumed, he seeks a second term in 2022? After all, the seeds of Davis' ouster were sown by his feeble reelection performance just a few months earlier.

That experience showed that a win isn't always a triumph.

On the day Davis was reelected, 6 in 10 voters disapproved of the governor's job performance, according to a Los Angeles Times survey. They had an equally dim view of Simon. So given that unhappy choice, many Californians took a pass on the race, or backed one of several third-party candidates; why not, since it was widely assumed Davis was going to win anyway?

The result was more than just an election-night humbling of the unpopular Democrat. The rock-bottom turnout made it much easier to force a recall vote less than a year later, a function of the state's exceedingly low qualifying threshold, which requires signatures reflecting just 12% of the ballots cast in the previous election. When Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger entered the contest, it was hasta la vista for Davis.

Republicans Larry Elder, Kevin Faulconer, John Cox and Caitlyn Jenner may all run again in 2022. (Assuming Jenner, who seems to be playing the role of candidate more than actually campaigning like one, hasn't latched onto some other merchandising scheme.) But it's hard to see how any of them would prevail if they can't beat Newsom in the recall, an oddly timed and likely low-turnout election that gives outsized influence to the GOP's highly energized base.

More significantly, a Republican doesn't need to receive anywhere close to a majority of votes — or, for that matter, anything even approaching Simon's 42% of the vote — to win election if Newsom is recalled. The candidate who gets the most votes, however few that is, will become California's next governor.

It won't be that way in 2022.

The more pertinent question, then, is whether a formidable Democratic opponent, or two, would feel encouraged to take on Newsom if he barely avoids being recalled. Blood in the water and all that.

Maybe so. California faces a shortage of rainfall, but no scarcity of ego and ambition. There are dozens of officeholders in Sacramento and Washington, stars in Hollywood, moguls in Silicon Valley and sundry people with piles of money who believe they could do a better job as governor, given the chance.

Still, it could be a heavy lift to defeat Newsom, however vulnerable he may appear. It's rare that a California governor is pushed out of office. The last incumbent to lose reelection was Democrat Pat Brown in 1966. Before that, Democrat Culbert Olson lost to Republican Earl Warren a quarter-century earlier.

Moreover, polls show Newsom maintaining strong support among Democrats, who outnumber registered Republicans nearly 2 to 1, and enjoying an overall favorable rating among most Californians surveyed. He's no Gray Davis.

"I'm not going to say it couldn't happen," said Garry South, who managed Davis' two successful gubernatorial campaigns and helped fight the 2003 recall. "But if you pick over the bones of history and look for an incentive to run against a sitting governor, however weakened he may seem, there's just no evidence, no receipts, to suggest it can be done successfully."

All of which heightens the stakes for both sides in the recall effort.

The vote Sept. 14 isn't just on whether to keep Newsom in office. More likely than not, it's also a vote on whether he should remain as California governor for the next 5 ½ years, until a second term expires in January 2027.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.