Column: My dad was a COVID-19 skeptic. But he got vaccinated, and so can your 'pandejos'

As my father stood in line for the first round of his Moderna COVID-19 vaccine on a sunny, chilly Saturday morning, I thanked God for our deliverance.

My sister booked the appointment the day before in less than 30 minutes. No nightmares with crashing apps, creaky websites, out-of-stock vaccines or deluded protesters like most Southern Californians have shamefully suffered so far.

All of that was the lesser miracle. The bigger one was that Dad was in line, period.

Let’s just say the Faucis and Ferrers of the world would scold my Papi if they ever met him. He has alternately claimed the coronavirus didn’t exist, was all hype, was a government conspiracy, or had already infected everyone, so caution was pointless. My siblings texted me any time he committed a faux pas: whom Dad talked to in person who wasn’t part of our pod. What places he visited besides his socially distanced Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. When he wouldn’t wear a mask at home.

Papi wasn’t a full-on pandejo (the Mexican version of a covidiot). Any time he messed up or babbled nonsense, I put him in his place, and he would stay there.

For a while, at least.

Part of the problem early on was that the coronavirus was opaque to him. Through the summer, Papi personally knew no one who had contracted the coronavirus. The other issue, frankly, is that he's a stubborn country macho who sees the world and all its maladies as something to dominate and not be afraid of.

Toxic masculinity is a hell of a preexisting condition to have during a pandemic. Too many of us, Latinos and not, have had to deal with it, to the point of broken friendships and strained familial ties.

But it can be defeated. My 69-year-old father is proof of this.

COVID-19 inched closer to him during the holidays, when Latinos in Southern California suffered inordinately. Two of his cousins died from it, followed by too many friends and conocidos (acquaintances). My uncle contracted la corona and survived; my sister’s godfather didn’t.

I figured the tragic turn would finally scare Dad straight. It didn’t. When COVID-19 vaccines became available, none of us were surprised that he refused it. You see, Dad told us, a compadre told him that vaccines had chips that would track you forever. The radio said people die after the first shot. And those were some of the more plausible pandejadas (pandejo-related stupidities) he offered.

We four Arellano kids collectively rolled our eyes and got him on a waiting list for the vaccine the second we could.

I agreed to take Papi — for moral support, and because he listens only to me since I'm the oldest. And, let's face it, a male. (There's that toxic masculinity.)

We promised him the whole thing would be simple: The vaccination site would be at an Albertsons parking lot in Santa Ana, just a 20-minute ride from his Anaheim home. It wouldn’t cost anything. We just needed to fill out a short form detailing his medical history, and show up at 9:15.

But when I arrived at my parents' house an hour before, Papi was back to his denialism. Now the excuse was that he didn’t need a vaccine because he has “strong blood.” Because God takes care of him. Because “I’m a very positive person, and that keeps me alive.”

I nodded along as I cooked a quesadilla on the comal and my siblings stayed in their room. Once the flour tortilla had toasted properly, I let him have it again. What about all his friends and relatives who had died? Did God not take care of them as well? Did they not have strong blood, or optimism?

More important, I pointed out as I drizzled Tapatío on my cheesy breakfast, the vaccine ultimately isn’t about you; it’s about us. Your kids and grandson and 98-year-old mother, whose hugs he misses.

That shut him up once and for all.

On the drive to the vaccination site, I reminded Papi of the smallpox scar on his arm. Its irregular, sunken shape always puzzled me as a child, and he always equivocated whenever I asked about it. My late Mami explained it to me early on: how smallpox and polio were a scourge in the small villages where both of them grew up in the highlands of central Mexico. And how everyone hailed the arrival of vaccines when the two of them were children.

I told Papi that his scar proved that vaccines are good and effective. I also mentioned how my mom always took us kids to all our vaccinations with pride. Medicine and doctors are meant to help people, after all. Medicine helped Mami fight ovarian cancer as long as she did.

Papi was in a better mood when we finally got to the vaccination line. I’m glad he was cheerful, because what initially played out before us were the racial inequities of California’s coronavirus COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

Exasperated Albertsons clerks, nearly all Latino, tried in vain to herd everyone into lines while the doctors on the other side of the lines smiled and checked paperwork and administered shots like clockwork. The supermajority of patients were white — this, in a supermajority Latino city. Nearly all of them were alone, wielding the smartphones necessary to nab a coveted spot online.

My father and I — he in cowboy boots and a face mask that read “Jerez Zacatecas,” me in baggy Dickies shorts and beat-up huaraches — stood out like Mexicans in a way I hadn’t felt in decades.

The mood was somewhere between fear and relief. No one was happy to be there, but everyone knew this was an important first step to beat the damned disease for good.

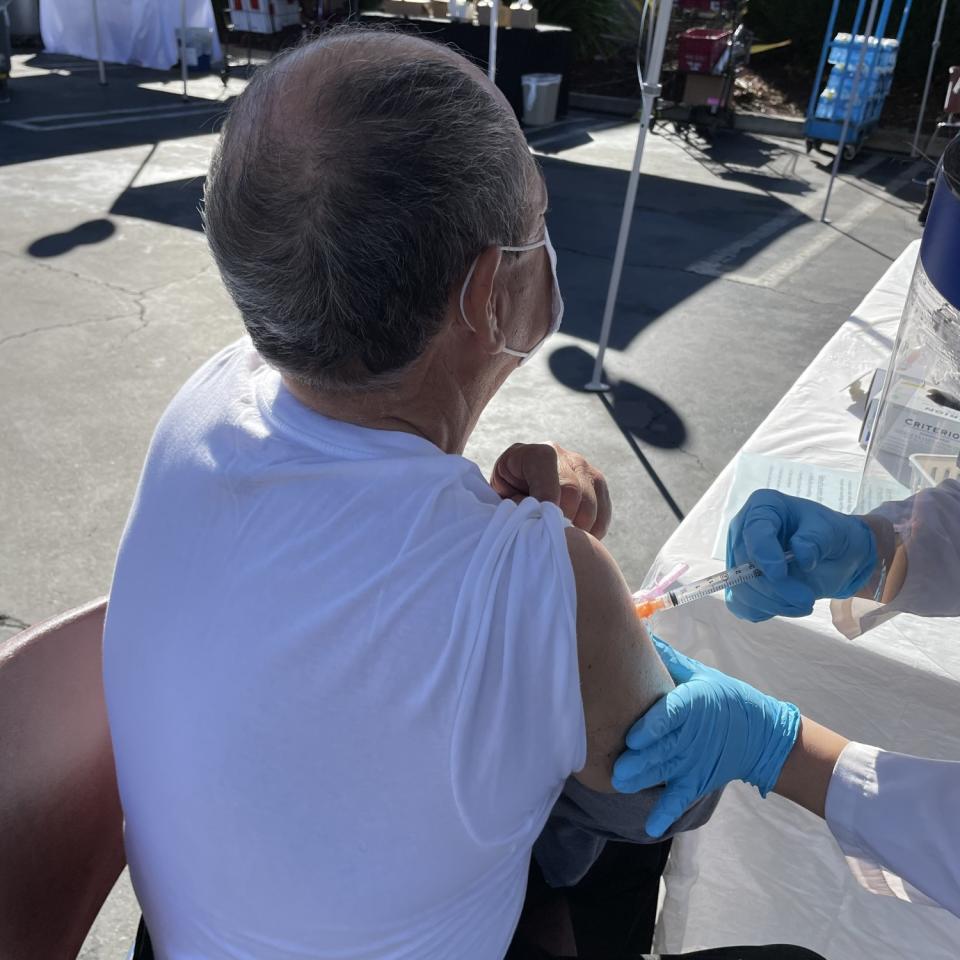

After that initial chaos, the rest of the process was seamless. There was a half-hour delay, but that's better than the hours-long ordeals that are the going wait-time right now. After Papi presented two IDs, a doctor asked him if he wanted the injection in his right or left arm. He chose his right one, where his smallpox vaccination scar is.

He took off a pea coat once owned by his cousin, who had died from COVID, and rolled up his sleeve.

The shot took about two seconds. Afterward, we sat for 15 minutes to see if Papi might suffer an allergic reaction, or turn into a Bill Gates-controlled zombie. Neither happened.

I told my dad I was proud of him as we walked back to the car, but that he still needed to practice good coronavirus safety. Then a Latino asked in Spanish how we managed to get the vaccine. He had tried and tried to get an appointment online for his mom, but had no luck.

We had no answer.

I’m going to return to the same Albertsons with my dad in a month for the second Moderna shot. If you have any family members or friends who remain skeptical of the COVID vaccine, my advice is to be patient but firm and stand your ground. And if the pandejos in your life still won't listen, have them hear the words of a former fellow traveler.

“Tell everyone Doubting Lorenzo — stubborn, country, macho — took the vaccine because he loves his family,” he said. “He took it for his children, grandson, and viejita mom, who’s very strong. And if Doubting Lorenzo took it, then no one has an excuse.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.