Column: 'Fortnite' maker draws praise for fighting Apple, but lawsuits allege it rips off kids

Epic Games, the creator of the stupendously popular video game "Fortnite," has been winning praise for its stance challenging the strangleholds of Apple and Google on in-app purchases by game players.

You might want to hold your applause.

The dark side of "Fortnite" in its various versions, according to lawsuits filed in federal court, is how it tempts children into spending their and their parents' money on virtual game items without fully understanding what they're doing and with little or no chance of obtaining refunds.

Like with a slot machine, Epic psychologically manipulates its young players into thinking they will 'get lucky.'

Allegation in lawsuit "R.A." v. Epic Games

"The games are targeted towards children," John E. Lord, a lawyer for a "Fortnite" player and his mother, told me in describing the lawsuit he filed for them in federal court in San Francisco. "Although they're offered for free, it's designed to induce in-app purchases."

A second lawsuit alleged that Epic deceived minors playing "Fortnite" by goading them into buying "loot boxes" known as "llamas" by implying the boxes might have valuable items inside — but they seldom do.

"Like with a slot machine, Epic psychologically manipulates its young players into thinking they will 'get lucky,'" that lawsuit stated. "These predatory practices are extremely affective [sic] when used on adults and are only intensified when used on minors."

The case was dismissed by U.S. District Judge Terrence W. Boyle in North Carolina after Epic refunded the money spent by the plaintiffs, parent Steve Alves of Valencia and his child, identified only as "R.A."

In the San Francisco lawsuit, however, Epic has rested its defense on its designation of certain in-app purchases as nonrefundable. This month, District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers refused to dismiss the entire case, brought by a California minor identified only as "C.W." and his mother, Rebecca White.

Rogers pared back some of the plaintiffs' claims but allowed the case to move ahead on their assertions that Epic violated California law barring "unfair" or "fraudulent" business conduct and that the company misrepresented or concealed whether and how purchases could be refunded. Evidence introduced by Epic showed that White's credit card was charged about $225 over three days in November and December 2018.

The plaintiffs are seeking to turn the lawsuit into a class action, encompassing California players. That class could number in the hundreds of thousands or more.

Epic argues that the plaintiffs are "suing to try to establish that any minor can demand a refund for any purchase at any time. We think this argument is wrong and will continue to fight this meritless lawsuit."

That's a broad interpretation of the plaintiffs' argument and glosses over the differences between purchases at bricks-and-mortar retailers and those made online, where the terms of the deal can be very murky and buried in purchase agreements that almost nobody reads. Epic also says it provides parental controls within "Fortnite" that parents can use to restrict their kids' purchases.

But the allegations in the federal lawsuits go beyond the specific interpretations of law brought before the judges. They paint a different picture of Epic from the one it painted of itself when it staged its attack on Apple's and Google's control of in-app purchasing.

As we reported, Epic in mid-August started allowing "Fortnite" users on mobile platforms to purchase gameplay items directly from Epic, rather than through Apple or Google as those companies' app stores require.

Apple and Google removed "Fortnite" from their app stores. Epic promptly filed suit against those companies, while launching a social media campaign under the hashtag #FreeFortnite. Opinion among the tech press and the immense "Fortnite" customer base seems to depict Epic as a David waging a valiant war against those two technology Goliaths.

Before we get into the details of the San Francisco and North Carolina cases, let's place them in the context of the nauseating practice of soliciting in-app purchases from children.

The vulnerability of children to insidious online blandishments isn't a new discovery. Nor has the practice been limited to independent video game companies. But it's especially questionable now, when pandemic-related lockdowns have confined children at home with few outlets for their energy or succor for their boredom other than online games.

Even before the pandemic, parents expressed concern about the addictive effect of "Fortnite" on their kids. Last year, the Quebec law firm Calex Légal launched a lawsuit asserting that "Fortnite" was designed to be "highly addictive," and that the game maker's failure to warn users of the potential for addiction violates provincial consumer law. The case is awaiting a ruling on whether to designate it as a class action.

In 2014, the Federal Trade Commission went after Apple, Amazon and Google, alleging in separate complaints that the three tech behemoths had billed consumers for charges incurred by children without their parents’ consent, measured in the tens of millions of dollars.

Apple agreed to refund at least $32.5 million, Google to refund at least $19 million, and Amazon more than $70 million.

In the Apple case, the FTC alleged that the company failed to warn parents that by plugging in a password for a single in-app purchase, they opened the window for unlimited further charges within a 15-minute window in which no further authorization would be required. The purchases generally ranged from 99 cents to $99.99.

In the Google case, the agency alleged that each authorization opened a 30-minute window for unlimited purchases.

Apple and Google settled the FTC complaints without admitting to or denying the allegations. Amazon's situation was different because the company demanded its day in court. This looks like a bad call: A federal judge in Washington, D.C., in 2016 upheld the FTC's assertion of Amazon's liability.

In the course of the trial, an Amazon employee explained that children's ability to spend their parents' money without specific authorization was considerable. “If a parent gives the device to a child and the child is playing the game and they — they just decide, you know, outside of the parent’s view or whatever, to purchase, they could do that,” he said.

Other evidence showed that the company was profoundly aware of the risk to parents' wallets because complaints were exploding to the point they resembled a "house on fire,” an employee had warned as early as 2011, adding that “accidental purchasing by kids” was “clearly causing problems for a large percentage of our customers.”

The FTC and Amazon finally settled the case and dropped their cross-appeals of the judge's order in 2017.

Many games and other online content that involve repeated purchases share features that may work against users' full understanding of the purchase terms.

Sometimes the nonrefundability of purchases is buried in lengthy end-user license agreements, or EULAs, that users habitually don't bother to read but click on buttons marked "agree" so they can start their downloads. Content providers and the tech platform companies know this, but it gives them legal cover to claim, "Hey, you agreed." Sometimes nonrefundability is noted on a purchase page but not necessarily all that prominently.

Also buried are provisions requiring disputes to be settled in arbitration, a forum that typically favors the companies, not the consumers.

Games and other entertainment apps are often offered as free downloads. The real money for the developers comes from egging players to buy game upgrades or virtual items — clothing, weapons, lives, skills, etc., etc. — that enhance the gameplay, as well as game currency used to buy the other items.

The cost of these items can be opaque even to adult users. Kids are at the developers' mercy.

That brings us back to the allegations in the lawsuits.

According to the San Francisco lawsuit, Epic doesn't provide a transparent or convenient way for minors to obtain a refund for unauthorized purchases, or any parental controls that would allow adults to monitor their kids' spending impulses.

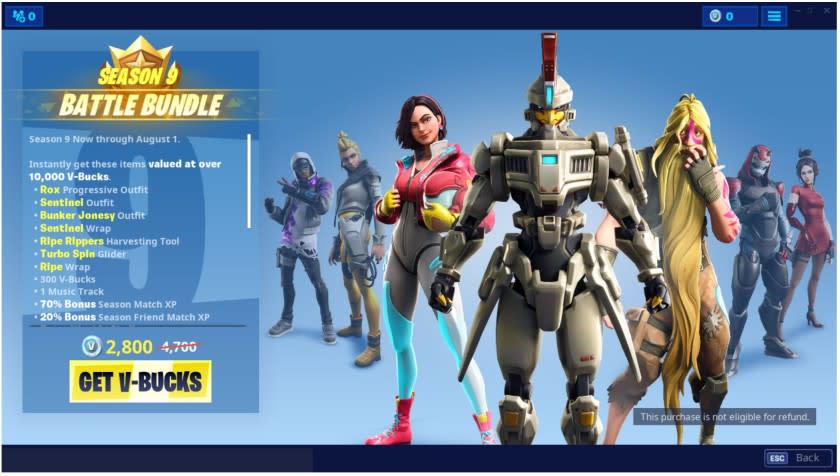

V-Bucks, the virtual game currency in "Fortnite," is structured to obscure how much real cash a user is spending. The game's digital content is updated as often as weekly, prompting users to spend money for the new content because the old content appears "stale," the lawsuit says.

V-Bucks are offered in odd packages, creating what the lawsuit describes as the "10 hotdog, 8 buns" trick — the amount of V-Bucks in a pack seldom corresponds to the price of items, so that users need to constantly fill out their V-Buck supply to cover their purchases. Once a payment method is entered and saved into the game, the player can use it without further authorization.

Epic doesn't generate an invoice for every purchase, the lawsuit says. As a result, parents whose credit cards are in the Epic system may not discover how much they've been charged until they scrutinize their statements, which might happen months after the charges are posted. Since individual purchases can be for only a few dollars at a time, they may not realize at first how the bills are piling up.

It's impossible to know just now how the San Francisco lawsuit will play out, but it's worthwhile to ponder the issue it raises.

First, Epic Games, its fellow game developers and the platforms through which these games are sold and played have long been on notice that features that allow underage users to make purchases with real cash — whether via credit or debit cards or gift cards — are inexcusable. Many of these games are aimed at minors.

The exploitation of children by Saturday morning cartoon shows was deemed socially, then legally, unacceptable decades ago. The FTC lowered the boom on Apple, Google and Amazon within the last decade. How could it be that these practices continue?

Second, it should be clear by now that content providers' EULAs — the core of their legal armory against consumer lawsuits — are a joke. The most recent EULA for "Fortnite" users runs 18 pages and more than 8,700 words bristling with dense legalese. The agreement states that it must be agreed to by an adult, but Oh Pu-leeze.

Software companies know full well that almost no one reads these things, so they know they can safely stuff all the legal fallbacks they wish into their texts. If the FTC really wants to clamp down on consumer abuse in the online world, it must mandate that key provisions be written in plain English and pushed at consumers in a way that makes crystal clear what rights they are signing away. We're nowhere near that yet.

Finally, consumers should always keep in mind that almost nothing online is free. "Fortnite" can be downloaded from the Epic Games website at no cost, but that merely indicates that Epic has learned an ancient lesson: Entice the marks with a free taste, and you can keep your hands in their pockets forever.