Column: The Los Angeles we love is dying in 2020. We must fight to save it

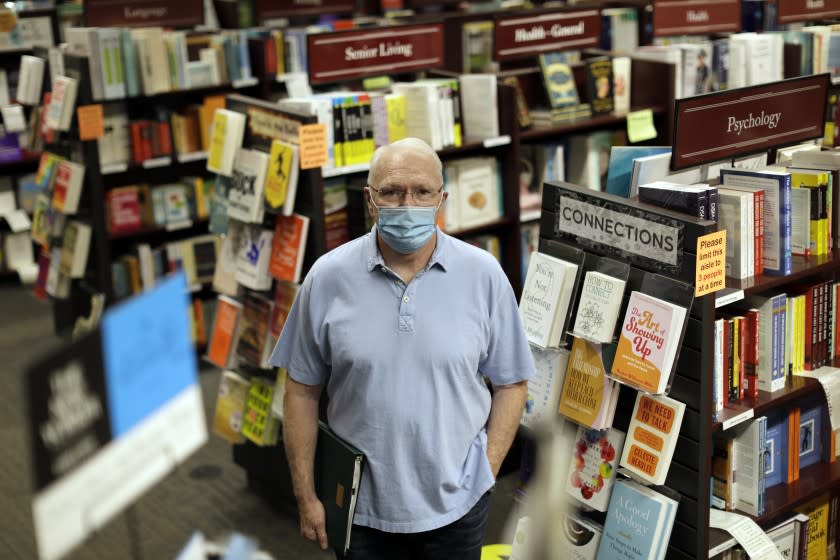

Bruce Abraham, 67, can recall his first trips to Vroman’s Bookstore in Pasadena.

He was 5 at the time.

“It would be heartbreaking to see this place fall,” said Abraham, a retired paralegal who lives in Sunland and visits the store “several times a week” for periodicals, books and browsing.

Upstairs, in the children’s book section, Alicia Procello and her son Martise told me they’re longtime customers, too. I asked Martise, now 12, how old he was when he first came in.

“Two,” he said.

“You can’t reinvent this place,” said his mother.

And let’s hope nobody has to. But Vroman’s has put out a plea for help to customers, saying the coronavirus may do them in. So has Chevalier's Books in Larchmont Village, another beloved local institution.

They’ve joined a growing list of local mom-and-pop stores and independent restaurants that are in trouble or have already shut the door for good. Given that we have no idea how long it will take for commerce to return to normal, I’m beginning to worry about what the Greater Los Angeles landscape is going to look like after the pandemic.

The Pacific Dining Car near downtown Los Angeles, with its late-night breakfast and tuxedoed staff, may not be taking on any more passengers, having sold off its fixtures and gone to selling steaks online. Stan’s Donuts in Westwood is finished after 55 years, and Chinatown’s Plum Tree Inn has checked out after more than 40 years.

I was talking to L.A. Councilman Mitch O’Farrell, who told me a lot of the businesses in his district are struggling, and then he mentioned that Musso & Frank Grill in Hollywood was suffering because it wasn’t set up for outdoor dining or takeout service.

My heart flipped. L.A. without Musso & Frank — which just turned 100 — is not L.A. They’d probably put an Outback Steakhouse there and I’d have to move to San Francisco or somewhere.

But not to worry.

“We’re undoubtedly going to open again,” said owner-operator Mark Echeverria. He told me the restaurant owned the building, so there’s no rent payment stacking up. In fact, he said, the restaurant is still covering healthcare premiums for its furloughed staff. But he, too, worries about Los Angeles post-virus.

“I am afraid L.A. is going to lose some of its historical identity,” Echeverria said. “I think as a city we need to rally around our history and support it as much as we can.”

OK, sure, change can be a good thing, and we live in an ever-evolving city. But can’t we keep some of the old, along with the new?

“Friends, the past few months have been the most difficult in our company’s 126-year history and Vroman’s needs your help to stay open,” the Pasadena bookstore’s owners wrote in a tweet to 21,000 followers.

I’m going to admit to two things:

One, a preference for local mom-and-pops over corporate businesses. They are, after all, a big part of the appeal and the spirit of Los Angeles, the land of a million scrappy, independent forays.

And two, a soft spot for Vroman’s.

With all the books, cards, magazines, stationery, housewares and novelties, it's like a small department store, but you can always find a quiet, carpeted corner, plop down with a book and feel as if you're in your own living room.

It's where we took my now-17-year-old daughter when she was learning to read and loved browsing the store’s huge second-floor children’s section, which was better than going to Disneyland. And long before that, my wife and I would meet at Vroman’s and then go to a movie next door at the Laemmle, which, by the way, is a local treasure that was struggling to survive even before the pandemic.

Actually, I have to admit to a third thing, even though it’s unflattering.

Last week, I wanted to buy a book for a friend, and without a second thought, I went into my Amazon account to buy it. Just after that I got an email from Vroman’s owner, asking if I wanted to drop by and talk about his struggle to survive.

What a fool and a hypocrite I’d been. With several months of limited travel and brick-and-mortar shopping excursions during the pandemic, I’d become even more addicted to the convenience of e-commerce. When I realized I could have ordered the same book from Vroman’s, or picked it up in person, I tried to cancel my Amazon order, but it was too late.

Joel Sheldon, the majority owner, did not kick me out of his store as penance for my sin. And I tried to redeem myself by buying the same book for another friend. But he said that for a store that had survived wars, recessions, the advent of big-box chain bookstores, e-books and even Amazon — the last two years were its most profitable ever — Vroman’s was reeling.

“Sometimes you get caught up in what I call sweeps of history, and it doesn’t make any difference how smart you are or how strong or well-financed,” Sheldon said. “You can be swept away by a tidal wave. We’re in a pandemic and it’s a tsunami.”

There’s a cruel irony in what’s happening to independent bookstores, Sheldon said. With more downtime, people are doing a lot of reading, but they’re not as inclined to leave the house, so they’re shopping on Amazon even though Vroman’s is a good local option for buying books online.

It’s a case of the rich getting richer, while neighborhood anchors — the kinds of places that are invested in their communities, and give them a sense of history, place and identity in a land of homogenous behemoths — slip further into peril.

UCLA professor Paul Ong told me he’s still analyzing research on the impact of the coronavirus on independently owned businesses in several Los Angeles neighborhoods, but some preliminary trends are already clear.

“On average, businesses in ethnic neighborhoods … are not faring as well,” said Ong. “We suspect that a number of these have gone under, and we’re talking to some community folks close to the ground who are saying that many of these businesses will not be back.”

Ong said Sherman Oaks, Larchmont Village and Venice have held on, but Chinatown has been hard hit, partly because of the xenophobia around whether the virus originated in China. In some ethnic neighborhoods, Ong said, merchants didn’t appear to have access to financial resources, or language barriers kept them from making full use of government assistance.

Another factor has to be that service industry jobs have been decimated, and residents of low-income ethnic neighborhoods have been devastated by both COVID-19 and lost spending power. But largely Latino Boyle Heights has fared pretty well, Ong said, and one theory is that major hospitals in the neighborhood help anchor the micro-economy.

The thing we can all do, if and when we have money to spend, is keep it close to home, which is a way of investing in all the independent store employees, as well as our neighborhood treasures.

At Vroman’s, third-grade teacher Lisa Gee was looking for books by poets Carol Ann Duffy and Seamus Heaney.

“I’d rather pick up a physical book here than look it up online, where you can’t browse,” said Gee, who drops into Vroman’s a couple of times a month. “I like coming here because this is the kind of place you don’t see anymore.”

Mary Paster, a linguistics professor and resident of Upland, drove in to fill a basket with books as her way of helping Vroman’s survive.

“Bookstores are important and a dying breed, and Amazon is just killing off all the independents. I would hate to lose this one, which has been here 126 years.”

People have long said that with thousands of books, pens and stationery, handbags, greeting cards and knickknacks for every room of the house, you can’t go into Vroman’s and not find a gift.

“I like their stuff,” said Paster, who displayed several items in her basket. “I’m doing some early Christmas shopping.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.