Column: Nearly 50 years later, he hasn't forgotten the ugly racial incident, and neither have I

It happened on a summer night almost 50 years ago.

I was a year or two out of high school, attending community college. My jock friends and I had gathered in a park in Pittsburg, just east of San Francisco, a working-class mill town that was diverse but divided. We did a lot of hanging out like that in our aimless late teens and early 20s, but that night was different, and unforgettable.

Well into the evening, fueled by beer, one of the revelers abruptly and for no apparent reason shouted out as ugly, vulgar and threatening a racial taunt as I've ever heard.

I didn't know the guy well. I wish I could say it was shocking, but it was just a more extreme version of the kind of thing you heard around town. I remember silence, and I remember the face of the one Black friend among us.

All eyes turned to Rod Ingram, who was shrouded in betrayal and resignation. He quickly got to his feet and quietly left. The rest of us didn't, and that has haunted me ever since.

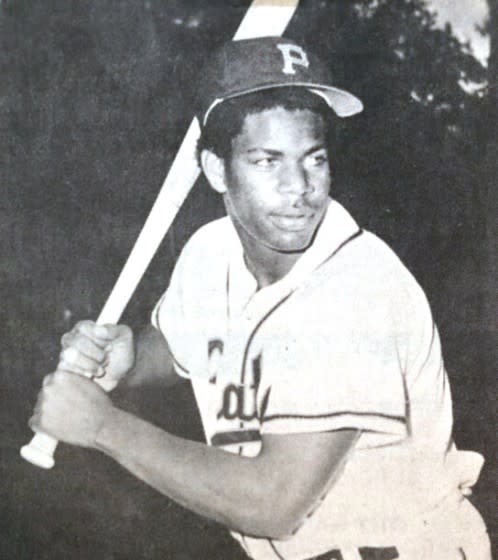

Rod and I had played baseball together as kids. For a time, I was a pitcher and he was the catcher, but he had something special. Rod’s bat was a rocket launcher, his arm was a cannon. The Cleveland Indians drafted him, but he played college ball instead. Then he got drafted by the San Francisco Giants. When a bum knee ended his dream, he became a teacher and later was head coach at St. Mary’s College.

In the town we grew up in, my white and brown friends and I said things that make me cringe today. Ethnic “humor” was so common you could convince yourself it was innocent, and Archie Bunker prototypes were everywhere. I remember the N-word being thrown around a lot, though not in mixed company.

In the park that night in the early 1970s, the dark truth of that town was exposed.

I think that was the last time I ever saw Rod, but every time I passed that spot, I saw his face, and I revisited my own cowardice and hypocrisy. Why didn’t I have the courage that night to tell the tough guy to shut up? Why didn’t I have the heart to walk away with Rod?

That night was the beginning of an awakening for me. I became increasingly restless, impatient, skeptical of everything I thought I knew and ashamed of everything I didn't know. I became determined to distance myself from the town and the people closest to me, and an eventual move to the East Coast was, in some ways, an act of rebellion that should have begun much earlier.

I began thinking about Rod again after George Floyd died under the knee of a cop in Minneapolis, because how could we not examine our own lives and the obvious evils of institutional racism and white privilege?

In America, still, every night is another night in the park.

Just over a week ago, I began trying to track down Rod. I thought I should apologize, finally, although that felt self-serving. And why should I assume he’d care to talk to me at all?

We'd spoken about the incident just once by phone, 10 years after it happened.

"I didn't think anybody remembered that night," Rod said on the phone, back in the early 1980s.

"I'll never forget it," I told him.

That conversation almost 40 years ago was brief, and awkward for me. After that, he went one way, I went another. When I began looking for him again, I didn't even know where he lived. And then I found out that Rod, at 66, has relocated to Florida and works there as a substitute teacher. I texted him, asking if we could chat, and he texted back immediately.

“You can call me anytime, Teammate," he wrote, adding a baseball emoji.

When I called him, we were instantly familiar, sharing stories all the way back to our days in Little League. We talked for nearly three hours and vowed to catch a game together, somewhere, when baseball is back in business.

If it was true that I'd thought about him hundreds of times over the years, Rod said, it sure took me long enough to reach out. And if I still felt bad about that night, he added, imagine how he felt.

“It was like being hit by a bolt of lightning,” he told me. “I had my 10-speed with me, and when I left I was sweating profusely. I don’t know if I ran any lights … but I felt like I was floating. It was not so much anger I was feeling, I was just bewildered.”

It wasn't, of course, that he was unaware of racism as a child, Rod told me. As a young kid, he said, he’d sometimes tag along with a white friend to the home of another white friend. They’d knock on the door of the house together, and he’d be asked by an adult to wait on the porch while the white friend went inside.

But Rod said he’d never heard bigotry expressed like it was that night. He figures now that if confronted today, the guy would say he didn't mean what he said, he was just young and dumb and said something stupid. Still, it was a violent slur by someone who was a classmate, if not a baseball teammate or close friend.

As for the baseball players who were there, Rod said he'd thought of us as longtime friends — part of a crew he thought he could trust. And yet we let him down.

“Some people call it tribalism,” Rod said. “That’s not judging things with your heart but going along with the crowd. I know you guys didn’t mean to hurt me, but everybody was there, and not one person said, 'Hey, Rod Ingram’s here.' I had to come to terms with that.”

The incident in the park was not the last one Rod had to deal with. A short time later, he said, two college dorm mates in Oregon walked behind him muttering the N-word.

Another time in Oregon, he was headed from his apartment to his car when two police officers ordered him into their vehicle and drove him around town without explanation. They finally told him there’d been burglaries in the area and there was a bad element in town. They dumped him out, a long way from his own vehicle, and said, “You be careful, n—.”

Back in the East Bay, where Rod worked as a teacher and high school baseball coach in the ’80s, he said the parent of an opposing team member called out, “Get off the field, n—.”

“My players heard it, and everybody in the stands heard it, and I’m standing there thinking, what do I have to do to not be disrespected like this?” Rod said. “I’m out here doing what I’m supposed to be doing, and you’re degrading me?”

Although I needed to distance myself from Pittsburg, I later learned that my hometown was no different from many others. Five decades on, East Coast and West, North and South, bigotry endures, the flames of hatred are fanned for political gain, and silent witness to injustice is no less a cancer than a knee to the neck.

Rod told me he doesn't know if the disease of systemic racism will ever be cured. But as he watches the news of Floyd and the other victims of police brutality, and he sees demonstrators of all colors marching for change, he said he is reminded of one of his favorite quotes from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.:

“History will have to record that the greatest tragedy of this period of social transition was not the strident clamor of the bad people, but the appalling silence of the good people.”