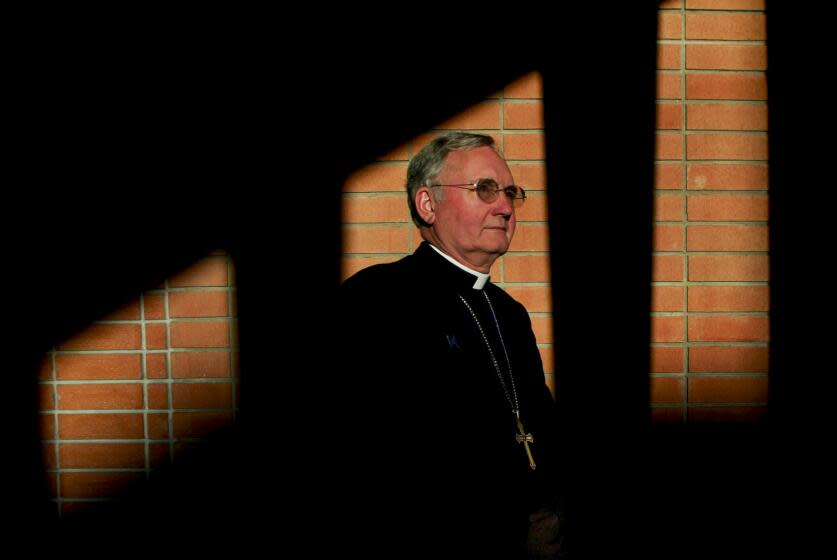

Column: No hosannas, only hypocrisy. Goodbye, Bishop Tod D. Brown

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

You’re not supposed to speak ill of the dead, so that explains the hosannas swirling around for Bishop Tod D. Brown.

The former head of the Catholic Diocese of Orange died Sunday at age 86 from lymphoma. Obituaries — including in this paper — noted his role in purchasing the former Crystal Cathedral in 2011 to make it a new base for Orange County’s 1.3 million Catholics. Online testimonials from the faithful praised his passion for Christ, his humor and his collaborative approach in leading a sprawling, multicultural diocese.

They also touched on Brown’s role in the sex abuse scandal that has permanently scarred the Catholic Church.

In 2004, as the bishop faced dozens of civil lawsuits filed by people who claimed that diocesan employees — priests, principals, lay teachers, school counselors —had sexually abused them over the past six decades, he published the Covenant With the Faithful. This was a set of promises posted in every parish that stated, in part, “We will be open, honest and forthright in our public statements to the media, and consistent and transparent in our communications with the Catholics of our Diocese.”

A year later, the diocese settled 90 lawsuits for $100 million, also releasing documents that proved most of the sex abuse allegations and the complicity of church officials in covering them up. At the time, it was the largest such payout in the history of the Catholic Church in the U.S., but it has since been — sadly — eclipsed many times over.

The Orange diocese website characterizes Brown’s moves during that era as “groundbreaking” and “unprecedented.” Brown, for his part, thought of himself as brave.

“I decided to settle because I was very concerned about the victims,” he told Orange County Catholic, the Orange diocese's official publication, in 2021, claiming that other bishops criticized his actions. “I made the decision in the context of prayer and consultation, and I have no regrets whatsoever. I believe I made the right decision.”

Spare me these hosannas. Congratulating Brown is like congratulating someone for towing their car after wrapping it around a pole.

Read more: SoCal's other wayward bishop

The Orange diocese sex abuse scandal was the first big story I worked on as a reporter. Through most of my mid-20s, I wrote multiple stories documenting how O.C.'s Catholic leaders not only knew that priests and employees were molesting children but frequently transferred them to poorer parishes and rarely bothered to alert law enforcement.

At the center of this scandal was Brown.

Most of the more notorious cases happened before he came to the Orange diocese in 1998. But Brown allowed priests who had admitted to molesting children to remain in ministry. Worse, the people who covered up for those molesters kept their jobs even after Brown took over — and were frequently promoted.

Take John Urell. He was the chief investigator for sex abuse claims in the Orange diocese under Brown and his predecessor, Norm McFarland. In 2008, when Urell suffered a breakdown during a deposition grilling him about what he knew and why he had stayed quiet for so long, Brown shipped him off to Canada for six months of treatment for "acute anxiety disorder." Afterward, Urell landed at a wealthy parish in South Orange County, where he remained as pastor until his retirement last year.

Then there was Jaime Soto. Brown consecrated the Stanton native as Orange County’s second Latino auxiliary bishop in 2000 even though Soto had pleaded for leniency in the 1986 case of Andrew Christian Andersen, who faced at least 56 years in prison for molesting altar boys in Huntington Beach. The judge agreed and let Andersen enter a treatment program in New Mexico, where he escaped, then was arrested for kidnapping and attempting to molest a 14-year-old boy.

Soto? He went on to become bishop at the Diocese of Sacramento in 2008 and remains in that position.

Brown's 14-year run featured stumble after stumble, yet apologists always tried to portray him as the antithesis of Cardinal Roger Mahony, whose mishandling of the sex abuse scandal in Los Angeles was so grave that L.A. Archbishop José H. Gomez stripped him of all public duties a decade ago. But Brown in some ways was worse even than Mahony.

While Mahony consistently stood by Latino parishioners, Brown shut down historic schools and parishes in Latino neighborhoods, which forced congregants to attend Vietnamese- and white-majority parishes.

When Mahony was accused in 2002 of sexually abusing a high school female student in Fresno during the 1970s, he didn't shy away from the matter, which law enforcement officials eventually determined was unfounded. When I broke the story that the Kern County Sheriff Department once investigated a claim against Brown, he claimed there was no reason to disclose it.

His rationale? “The ‘Covenant With the Faithful' does not require the disclosure of allegations which have no credible or factual basis,” a diocesan press release stated — never mind that Brown himself had outed priests who were wrongfully accused.

Even Mahony didn't have a case as preposterous as that of John Lenihan, a popular priest at St. Edward the Confessor in Dana Point. Brown let Lenihan stay in his position even though the priest had admitted to molesting a teenage girl in the 1990s, a scandal I remember very well because I was a teenager and Lenihan was the pastor at my home parish of St. Boniface in Anaheim at the time.

When Lenihan anonymously admitted to my colleague Steve Lopez in 2001 that he had repeatedly broken his celibacy vows, Brown forced him to resign within weeks, telling parishioners in an open letter that Lenihan’s admission was “a cause of scandal to many in the Church, and it is a cause of great concern to me.”

In Brown's world, molesting an underage girl was redeemable — but having consensual sexual relationships with adult women was unforgivable. Remind me again why some Orange County Catholics are remembering Brown as a hero?

Read more: O.C. bishop dies: Tod David Brown settled church sex abuse suit, apologized to victims

Few know the truth about Brown better than John Manly, the attorney who has won more than a billion dollars worth of sex abuse settlements — against the Catholic Church as well as USC, former USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar and the Los Angeles Unified School District. Manly represented multiple plaintiffs in the 2005 Orange diocese settlement and got his start in 2001 by helping to secure a $5.2-million settlement — at the time, one of the largest individual cases against the Catholic Church — and a zero-tolerance vow by Brown.

Soon after, a priest was caught with child pornography on his laptop, but Brown allowed him to stay until a church whistleblower talked to the media two years later. His reasoning? The priest hadn't technically molested anyone and thus didn't violate the Orange diocese's zero-tolerance policy.

“The diocese settlements with survivors were done at the point of a legal gun,” said Manly, who is now representing plaintiffs in 28 civil suits against the Orange diocese. “They were not the result of some saintly largess of Bishop Brown, as is now suggested." If the cases that settled had gone to jury trials, the financial rewards could have been even larger.

It's been years since I thought about all the stories I wrote about Brown, maybe because they're painful. When I started reporting on the sex abuse scandal, I was a church-going Catholic who thought most of the allegations against priests were made by money-hungry heretics. When I discovered the gravity of the situation, I felt confident that Brown would clean house and change his ways.

When none of that happened, I stopped attending Mass. To this day, I only go to church for funerals and the occasional wedding.

You're not supposed to speak ill of the dead, so I guess I should say something nice about the late Orange County Catholic leader. But that would be hypocritical. That would be Bishop Tod D. Brown.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.