Column One: L.A. Pride at 50: 'In the beginning it was about visibility. We're here. We're queer. Get used to it.'

Lillian Faderman can tell you exactly where she was standing on June 28, 1970: at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Highland Avenue.

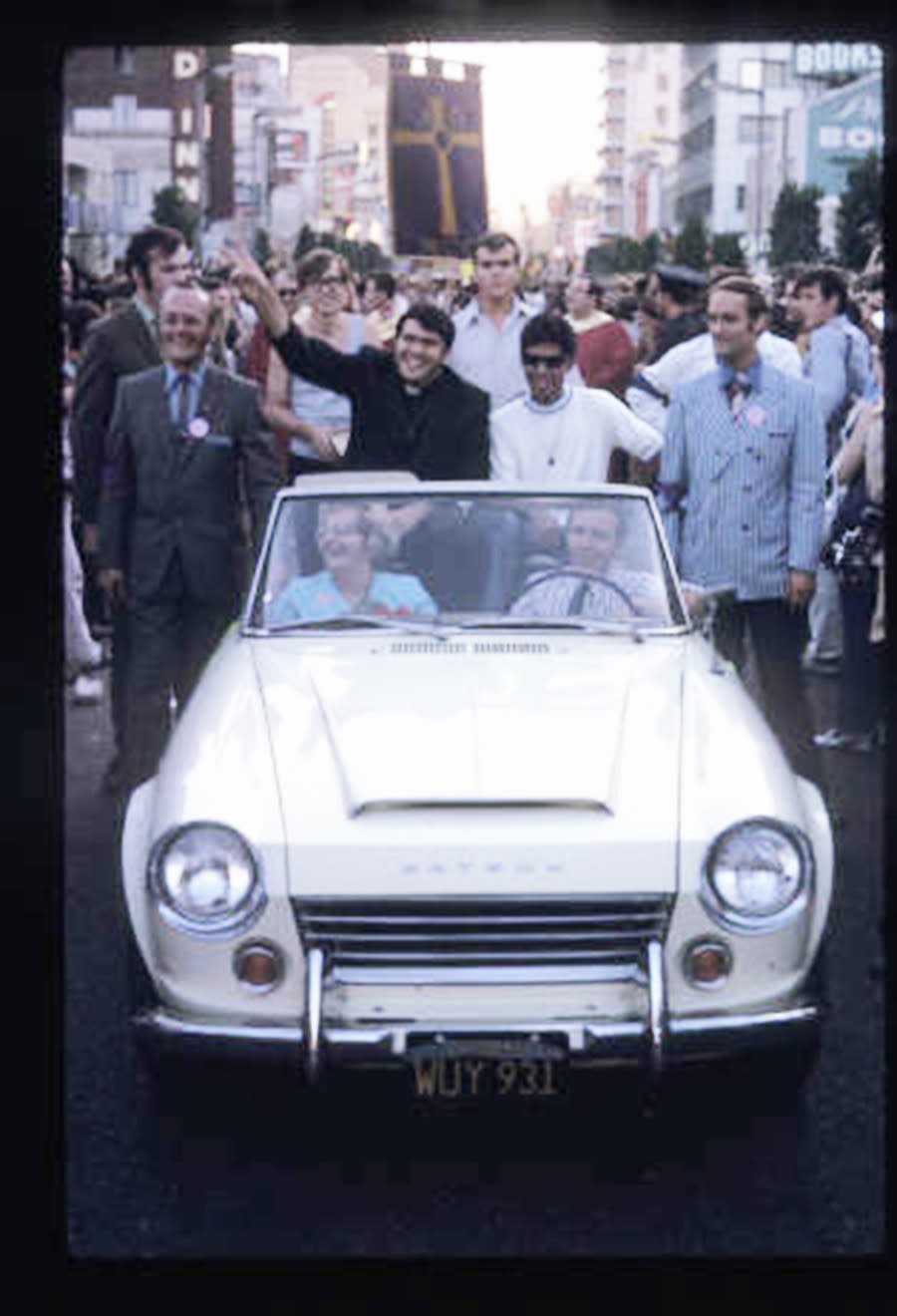

She no longer feels the tears that coursed down her cheeks at that busy corner on that summer night. But she will never forget the scene that caused them: hundreds of people marching down Hollywood Boulevard in the nation’s first legally permitted gay pride parade.

There were men bedecked in fairy wings. Go-go dancers on a flatbed truck. The Metropolitan Community Church choir in flowing robes singing “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

“I just remember thinking, ‘This is so fantastic,’” Faderman said of that long-ago celebration. She was 30 at the time, and she watched the parade in front of a diner called Coffee Dan’s, her partner by her side. “I remember crying. Who could believe [the parade] would happen in this area, where it was so scary to be gay?”

Over the last 50 years, that first ragtag parade evolved into the annual L.A. Pride observance, a controversial, three-day extravaganza drawing hundreds of thousands of spectators and costing millions of dollars to stage. But what should have been the biggest celebration in its long history — its 2020 golden anniversary bash — was a dim vestige of every Pride event that went before it.

Live Pride functions were canceled because of the coronavirus, replaced in late June by a televised and live-streamed “virtual parade,” which felt like a three-hour Zoom meeting with commercials and Disney rainbow merchandise.

An All Black Lives Matter march to pay homage to Black transgender people was held June 14, the date originally chosen for the 2020 Pride event, in West Hollywood, Pride’s usual place; it, too, was mired in controversy.

When L.A. Pride emerges from quarantine at some foggy date in the future, chances are it won’t look much like its old self. The parade, which moved to West Hollywood in 1979, is leaving its longtime home and heading off for parts unknown.

West Hollywood officials must reimagine a future without the blockbuster event in their city, which was incorporated to great acclaim in 1984. The Christopher Street West Assn., which has produced L.A. Pride from the start and owns the name, must find a new venue for the parade.

While organizers figure out what L.A. Pride’s next chapter might bring, they would do well to look to the celebration’s past: to the painful events that led to that first foray down Hollywood Boulevard; to the men and women who were there 50 years ago, whose numbers are dwindling fast; to a time when politics and partying were in better balance.

To the summer of 1970.

**

L.A. Pride began with a letter.

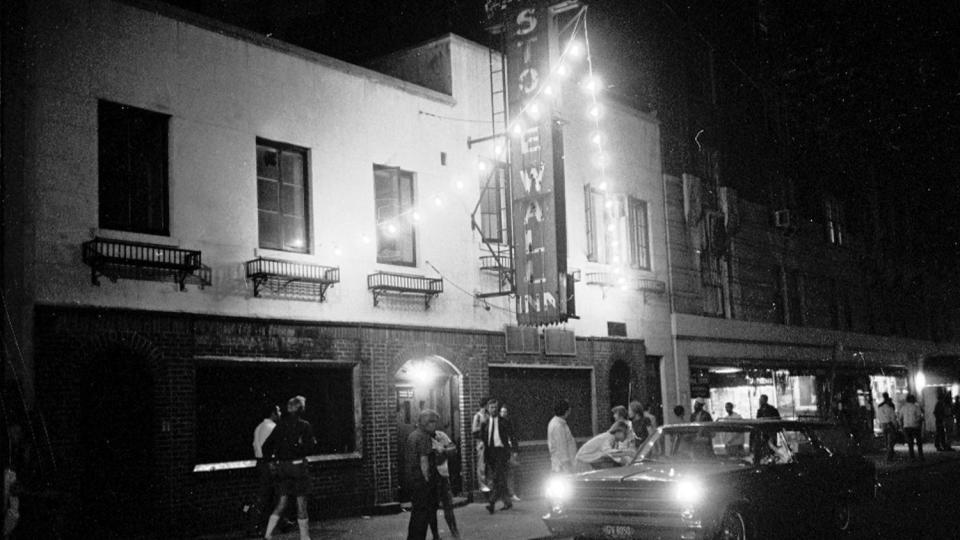

In June 1969, New York police had raided a Greenwich Village gay bar called the Stonewall Inn. Unlike at other raids, this time the patrons fought back, changing the face of the gay rights movement.

As the first anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion neared, activists in New York wanted the uprising commemorated around the country. Looking to Los Angeles, they wrote to Morris Kight, a well-known peace activist and co-founder of the Gay Liberation Front, asking him about organizing an event. What happened next depends on whom you talk to.

This is how the Rev. Troy Perry, founder of the Metropolitan Community Church, tells it: “Morris said, ‘I think we ought to have a demonstration.’ I said, ‘No, no, no. I think we ought to have a parade. This is Hollywood, this is L.A. ... Let’s celebrate our pride.’”

The first time Perry, Kight, and their friend Bob Humphries went before the Los Angeles Police Commission to ask for a parade permit for Hollywood Boulevard, Perry did the talking. He wore a black suit and a white minister’s collar. The permit was in the church’s name. The men decided not to use the word “homosexual” right off the bat. They figured their chances with the conservative commission might be better that way.

They were wrong. The commissioners already knew who they were. They pressed Perry about just whom he represented. They asked about “this ‘church,’ in quote marks,” said Perry, whose church was one of the first in the world to embrace homosexuals, as they were referred to at the time. Finally, he’d had enough.

“I said, ‘I represent the homosexual community in Los Angeles,’” Perry recounted. “You would have thought I’d shot someone in the room. It got very nasty, very quick. I could hear it in their voices. [Police Chief] Edward M. Davis said, ‘I’d rather have thieves and burglars march down the street.’”

The commission granted the parade permit, but with onerous conditions, including a $1-million bond “to pay for the property damage that will happen when people throw rocks and bricks at you,” Perry said. And a $500,000 cash bond to pay for police to protect the gay marchers.

The three men left. Kight called the ACLU, which sued the police commission. Eventually, a judge found in their favor. But by then, it was June 26, just two days before the parade was set to kick off.

“We thought we were going to lose, and we didn’t even have a parade ready,” Perry said, laughing. “We called every gay and lesbian group we knew of. I told one group, ‘Listen, we’re having a pet section. Tell them they can walk their pets.’ ... They showed up with their birds, dogs, a boa constrictor.”

One young participant marched with his Alaskan husky, which wore a doggy version of a sandwich board, signs hanging down its furry sides that read, “We don’t all walk poodles.” Man and dog made Time magazine.

Five years later, Christopher Street West invited Davis to take part in the 1975 celebration of Gay Pride Week. The police chief, to nobody's surprise, declined.

“I would much rather celebrate ‘GAY CONVERSION WEEK,’” he wrote to the Pride celebration organizers, “which I will gladly sponsor when the medical practitioners in this country find a way to convert gays to heterosexuals.

“Very truly yours, E.M. Davis, Chief of Police”

**

For Faderman, that first pride parade was an exorcism for the haunted corner of Hollywood and Highland, “a wonderful scene in 1970 to answer those bad memories of the 1950s.” The police harassment. The secrecy. The shame.

Coffee Dan’s, where she watched the inaugural event, was her high school hangout in the 1950s, where “the gay kids” would congregate. The police would arrest them there — mostly the boys. And one girl, Frankie Hucklenbroich, who “was busted,” Faderman said, “because she was very butch and very tall.”

“We were teenagers,” said Faderman, now 80 and a renowned historian of LGBTQ life. “She was looking for a job. I suggested maybe she couldn’t find one because she wore pants. So she borrowed a skirt and high heels, maybe from a drag queen, and a tailored jacket.”

But when Hucklenbroich arrived at Coffee Dan’s to wait for Faderman after a futile day of job hunting, she was quickly arrested — for being a man dressed as a woman. She protested, telling the officers they had it all wrong. She was a woman, she told them. Really.

“The police matron took her into the bathroom,” Faderman said, “and made her prove it.”

Police harassment of gay men and lesbians lasted long beyond 1957, when Hucklenbroich walked out of that coffee shop restroom, her face pale, her eyes, Faderman wrote in a 2003 memoir, “looking as if she’d been flogged.”

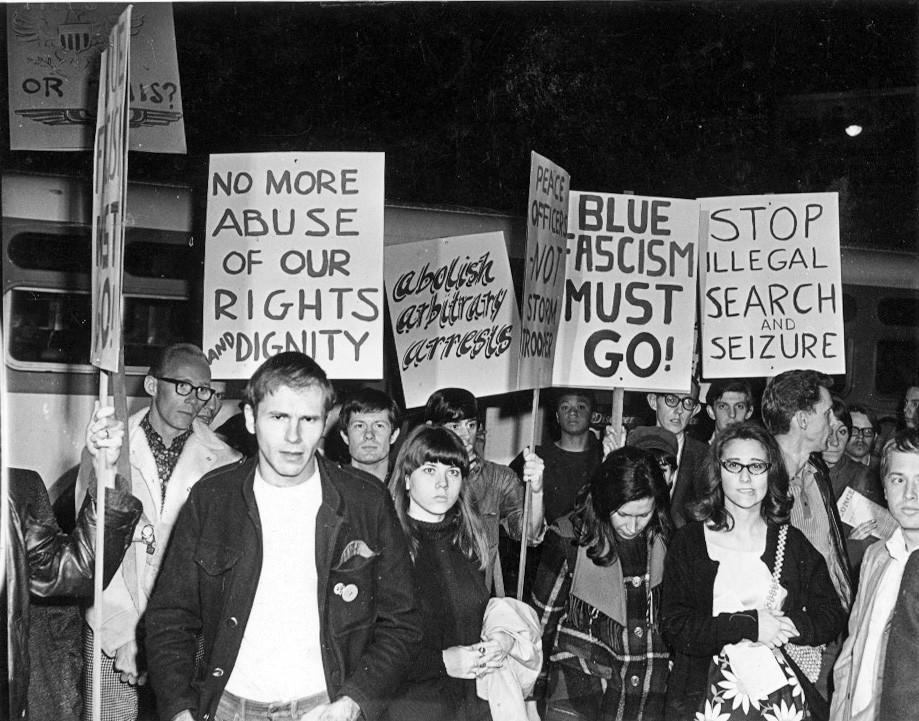

Three people who were killed by police or died in Los Angeles Police Department custody in 1969 and early 1970 were remembered at the first gay pride parade down Hollywood Boulevard. Banners, signs and fliers at the event pleaded for the LAPD to investigate the deaths, to no avail.

Biographer Mary Ann Cherry likens that marching memorial half a century ago to the nationwide anti-racism protests in 2020 after Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd were killed.

“It was very much as we say now: ‘Say their names,’” Cherry said. “They were three fellow homosexuals — one, transgender — who were killed at the hands of the LAPD: Larry Turner, Howard Efland and Ginny Gallegos.”

Cherry wrote about the three deaths, Pride 1.0 and the politics that shaped the event's early days in “Morris Kight: Humanist, Liberationist, Fantabulist: A Story of Gay Rights and Gay Wrongs,” her 2020 biography of one of the original organizers.

“Marching in any of the first gay pride parades took unprecedented displays of courage,” Cherry wrote. “To ‘come out’ in 1970 could be seen as openly admitting to being a deviant, evil or perverse.”

But to march down the street, “declaring oneself a homosexual,” she continued, “would surely mean the mark of insanity.”

**

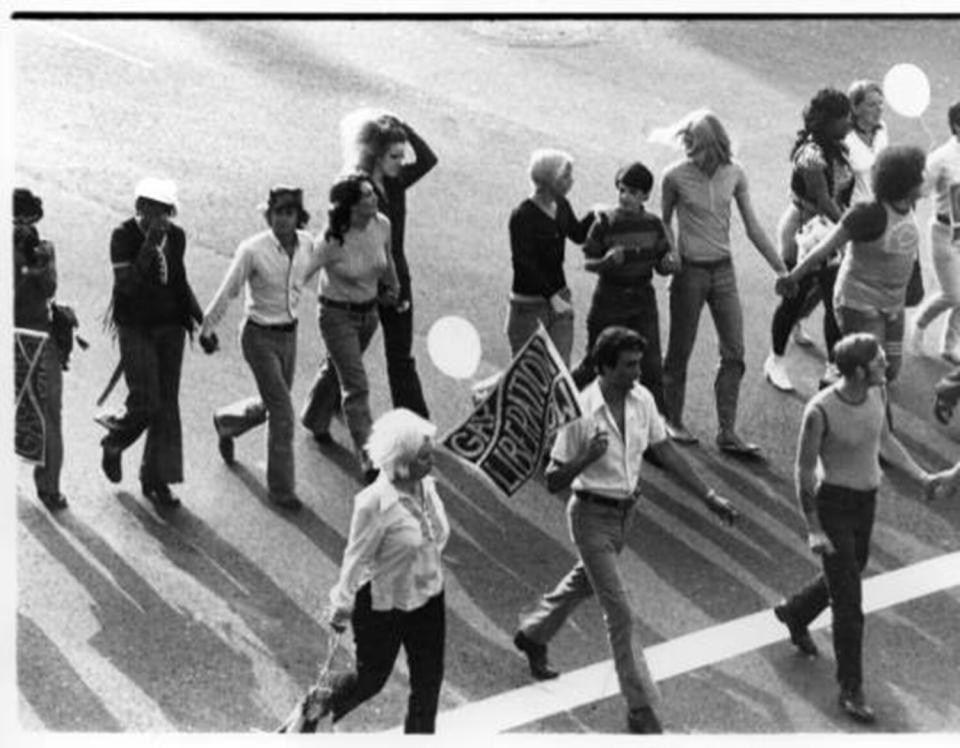

Alexei Romanoff marched down that street 49 times.

Each time, he marched as a proud gay man.

He marched in 1970, during the first gay pride parade, when the LAPD feared violence but got a traffic jam instead. In 1988, when hundreds of purple and white balloons were released in memory of those who died of AIDS. In 1994, when gay and lesbian LAPD officers marched in uniform for the first time, cheered on by an estimated 250,000 spectators. In 2014, when two same-sex couples were honored as the lead plaintiffs in the lawsuit that struck down California’s ban on same-sex marriage.

And Romanoff marched in 2017 as grand marshal with his husband, David Farah. That year, the parade honored the 50th anniversary of a different milestone in gay history: the Black Cat protests of 1967.

Two years before the Stonewall Rebellion, Romanoff helped organize one of the first large public demonstrations anywhere for gay rights. The action sprang from a series of LAPD raids on Silver Lake gay bars, including the Black Cat Tavern, which resulted in dozens of arrests and left several men and women badly beaten.

Romanoff is 84 now. His eyes are still bright blue, but his memory has begun to fade. He is the last known organizer of the Black Cat protests. He is one of a small group of men and women still around who witnessed the birth of L.A. Pride.

And he is believed to be the only man or woman who has marched in every L.A. Pride parade. (There was none in 1973, and 2020 succumbed to COVID-19.) He plans to take part again in 2021.

He marches, he said, because of Mother Bryant, an elderly gay man, whose real name he never knew, who taught Romanoff and his friends about respect and resilience over meals at a Horn & Hardart automat in the 1950s in New York City.

Mother Bryant was born in the late 1800s in small-town America and came of age at a time when, he told Romanoff, if the police found out you were gay, they would “come by almost every day and beat you until you moved out of the town.” They didn’t want you arrested, he said. They wanted you gone.

“He said to a group of us at the table, ‘When you get to be my age and live in this world, you have to remember one thing,’” Romanoff recounted. “‘You have to respect yourself and respect the world. And you have to be proud of who you are and not ashamed, because that’s how God made you.’”

Romanoff marches, he said on a sunny morning at the end of Pride Month in June, “for human rights. I’ve marched for equal rights. I’ve marched for Black people’s rights. I’ve done all sorts of things, because while one person in the country is less than another, we haven’t achieved what we need.”

He marches, he said, “because I’m not ready to quit yet.”

He marches because the work is not done.

**

It’s anyone’s guess what L.A. Pride will look like in 2021.

For half a century, it was a reflection of LGBTQ life in Southern California. The 1970s were about visibility. The ’80s mourned the thousands of gay men who died of AIDS. Some 21st century parades celebrated marriage equality and other civil rights issues. In 2017, Pride turned into the Resist March, a protest against the election of President Trump.

In recent years, however, Pride has been slammed as too white, too male, too drunk, too expensive, too corporate, too frivolous. It was as if everyone had forgotten how and why it all began. The All Black Lives Matter march, critics said, was another example of Christopher Street West’s stumbling; the association did not reach out to the Los Angeles chapter of Black Lives Matter before announcing the march.

Gerald Garth is a CSW board member and a member of All Black Lives Matter. He acknowledges that “the West Hollywoods of the country, a lot of the LGBT-affirming spaces ... have turned into this young, white, male-dominated space.” But he said CSW “has really begun to address its history and its legacy of noninclusion.”

Part of L.A. Pride’s problem, said West Hollywood Councilman John Duran, as the council prepared to vote on the event’s fate in late July, is that the parade and festival “lost sight about what the whole weekend was supposed to be about.”

In June, Duran and Councilman John D’Amico proposed that the city open production of the annual parade and festival to bidders other than Christopher Street West. The association responded with a letter to the West Hollywood City Council: L.A. Pride was leaving town.

Estevan Montemayor, CSW's president at the time, declined to comment on the departure. Sharon-Franklin Brown has since been named president of the CSW board; she is the first Black transgender woman to serve in that capacity.

Brown said in late September that the group would "be announcing news regarding L.A. Pride 2021 in the next few days and months."

Three days after CSW announced its departure, the West Hollywood council voted to start a “visioning process” to figure out how residents want their city to celebrate Pride. It is scheduled to vote in late October on hiring a consultant to guide the process.

Moving forward, Duran said, anything goes: “I think we have to be prepared to just open all the structure, the framework, the limiting boxes, the past, and start with a completely clean slate.”

**

For her part, Faderman hopes Pride celebrations never wipe the slate completely clean, never forget where they came from and why.

“Not only as a historian, but as someone who came out in the 1950s, I remember well the truly bad old days,” she said.

It’s not as if the LGBTQ community “has reached nirvana.” Far from it.

“I just remember how terrible it was for us,” she said. “In every direction. Wherever we looked.”

Times staff writer Hailey Branson-Potts contributed to this article.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.