Column: This is the only California county that's coronavirus-free. Masks are optional

In the high desert of Modoc County, a remote expanse of mostly nothingness between Oregon and Nevada, almost no one wears a face mask.

I figured this out one morning last week, when I strolled into the sparse but well-kept office of Sheriff William "Tex" Dowdy. He took one look at my mask, and a bemused smirk spread across his boyish — and, yes, bare — face.

Then he choked down a chuckle and shrugged.

“Do whatever you want to do,” Dowdy said. “You have a choice here.”

A “choice” of this sort is not something most of us get anymore — and with good reason. We're in the middle of a pandemic that has killed more than 130,000 Americans, including 6,500 Californians, and, after a brief lull, is sending more people to hospitals than we saw even in April.

Not wearing a face mask is reckless. But in some strange way, it seems a little less so in Modoc, the only county in California that has yet to report a single case of the coronavirus.

Here, residents greet one another with hugs and hearty handshakes. They go out to lunch with coworkers, sitting elbow to elbow. They laugh with abandon and slap each other’s backs without immediately slathering themselves in hand sanitizer.

And yet, while people aren't exactly lining up around the block to get tested, the county's main hospital is empty and no one has come down with COVID-19.

No one knows why they've been spared, although everyone seems to have a theory. Most insist it's because only about 9,000 people live in the county, most of them on far-flung farms and ranches dotting 4,200 square miles of brush and rocky cliffs.

At the very least, the ultra-low people-to-acres ratio of Modoc County compared with, say, Los Angeles County raises questions about why the state would use any sort of one-size-fits-all approach to fighting the coronavirus.

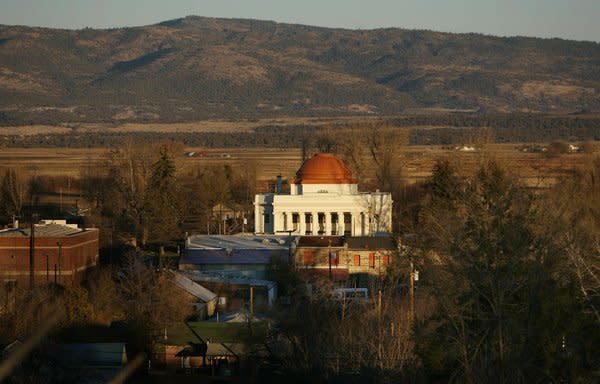

The only city in the county to speak of, Alturas, has traffic lights that blink yellow, and Main Street is filled with more long-shuttered storefronts than actual operating businesses. In addition to a cafe, a small gym and a movie theater that is still shut down, there's a hair salon. It has four chairs, and people tell me that there are never four people in there at the same time.

Dowdy sees himself as defending this way of life, frequently extolling the virtues of "personal choice" and "common sense."

“It’s kind of insulting for the state or anybody else to think that we don’t have the common sense to do the right thing,” he told me. “And the right thing is different depending on the person. We all have our rights.”

He says he's not trying "to poke the governor in the chest."

But it was Modoc that was the first county to reopen its economy, weeks after Gov. Gavin Newsom had ordered all Californians to stay home and to shut businesses to slow the spread of the virus. Dowdy's office submitted a plan but didn't wait for official approval from Newsom's office before moving forward.

And then, last month, Dowdy was one of the first sheriffs in the state to announce that he wouldn’t be enforcing Newsom’s mask order. That prompted the governor to threaten again on Monday to withhold funding from counties that didn't cooperate with state health directives, including making sure people cover their faces in situations where social distancing isn’t possible.

Even though any reduction in state funding would surely decimate his already cash-strapped Sheriff’s Department, Dowdy isn’t backing down.

“I totally support the fact that if somebody wants to wear a face mask, please do so,” he said last week. “If you feel that that’s some protection for you or your family. I feel it’s a personal choice.”

I guess Dowdy figures he's no Vernon Warnke. Back in May, Warnke, the sheriff of Merced County, was defiant. He refused to enforce the state's stay-at-home order because, he argued, the governor didn't have the right to issue it in the first place and it would lead to “economic slaughter.” But now, with the rural Central Valley county on the state’s coronavirus watch list, Warnke is telling people to “wear your masks, do your social distancing, wash your hands.”

Things can change, but Dowdy is adamant. Even if there were to be an outbreak in Modoc County, he told me, he wouldn't enforce the mask order, because residents have common sense.

"I think you would see more people wearing them, but I don't think it's something that I necessarily need to come out and tell people to do," Dowdy said. "It's very frustrating to me to think that the government believes that we're so ignorant that they have to tell us what to do."

The sheriff seems to know full well what many people in more populous parts of California must think of him.

That he’s shortsighted and selfish, given the science showing that a face covering helps slow the spread of the coronavirus. Or that he’s merely a product of a hopelessly unreasonable, right-wing environment. (It's true that nearly 72% of voters in Modoc County went for Donald Trump, and the people soliciting signatures to recall Newsom from office don't have to work very hard.)

But he doesn’t seem to care.

What he does care about is how Modoc County is in a perpetual state of waiting. Waiting on Newsom to issue more public health orders to counties. And then waiting for a clear explanation on what counts as compliance with the state. But most of all, it's waiting for a pandemic that has yet to arrive.

Early on, the county cleared out its small, rural hospital, telling patients to come back later and erecting a white emergency tent outside for those with COVID-19. It willingly shuttered schools, as well as the handful of small businesses in Alturas and neighboring Cedarville.

County officials pulled out and distributed all of the heavy-duty face masks and other personal protective equipment they had squirreled away after seasons of wildfires.

"We were well prepared," said Dowdy, whose office coordinates emergency services for the county. "And that sounds strange coming from a very, very, very small county, but we were well prepared."

Then, nothing.

Residents had resisted the temptation to hoard supplies, knowing the county's already tenuous supply chain — with food, toilet paper and other goods being trucked to a handful of local stores a few times per week — was being disrupted by the broader pandemic.

Many worried about the cash-strapped rural hospital being unable to make ends meet without paying patients, and the toll being paid by students who, rather than going to school, were in troubled households.

Two of the main restaurants in Alturas were struggling to survive, in part because they had to figure out how to handle delivery. Luckily, some enterprising high school students decided to make a business out of it, charging a few bucks to bring food to the farthest reaches of the county.

"Have you been up and down Main Street? There's quite a few closed storefronts, and that was before COVID," Dowdy said. "So we didn't need any more of that."

Without those stores, residents knew, everyone would have to make the two-hour-plus drive to Redding or Reno just to get basic supplies.

Like many other side effects of this pandemic, it has taken a hammer to existing fault lines in rural communities. So, feeling as if they had little choice, Modoc County officials agreed to start reopening the local economy faster than other parts of California.

So far, Dowdy said, he hasn't heard anything from Newsom's office to indicate that Modoc County is out of compliance with the state. But the sheriff admitted that the governor's messaging is often confusing or nonexistent, so he's still a bit worried.

Dowdy isn't alone in this assessment. A growing chorus of critics has emerged in recent days, dinging Newsom for being inconsistent, unfocused and tone-deaf. Even in far more populous parts of California, like Los Angeles, it seems impossible to get a straight answer about what's open, what's closed and, most important, why.

Heck, I'm still trying to figure out why Newsom closed the beaches but initially let restaurants and bars that serve food — you know, like potato chips — stay open last week.

It's no wonder that many in Modoc County, where antipathy toward big government was already a thing, now feel confused, a little duped and angry that they allowed themselves to trust Newsom's administration at all.

"Our rights as American citizens," Dowdy said, explaining residents' fears about the loss of local decision-making. "I feel like that's slowly being taken away, and that is concerning to me."

And yet, making a habit of refusing to wear a face mask just because Newsom ordered everyone to wear a face mask is hardly a hill worth dying on — unless the goal is actual death. That's a choice, too.