Column: 'Placing History' adds important chapter to South Bend's Black history

There were joyful moments, interspersed with those heavy with meaning, at Tuesday’s launch of "Placing History: An African American Landmark Tour of South Bend, Indiana."

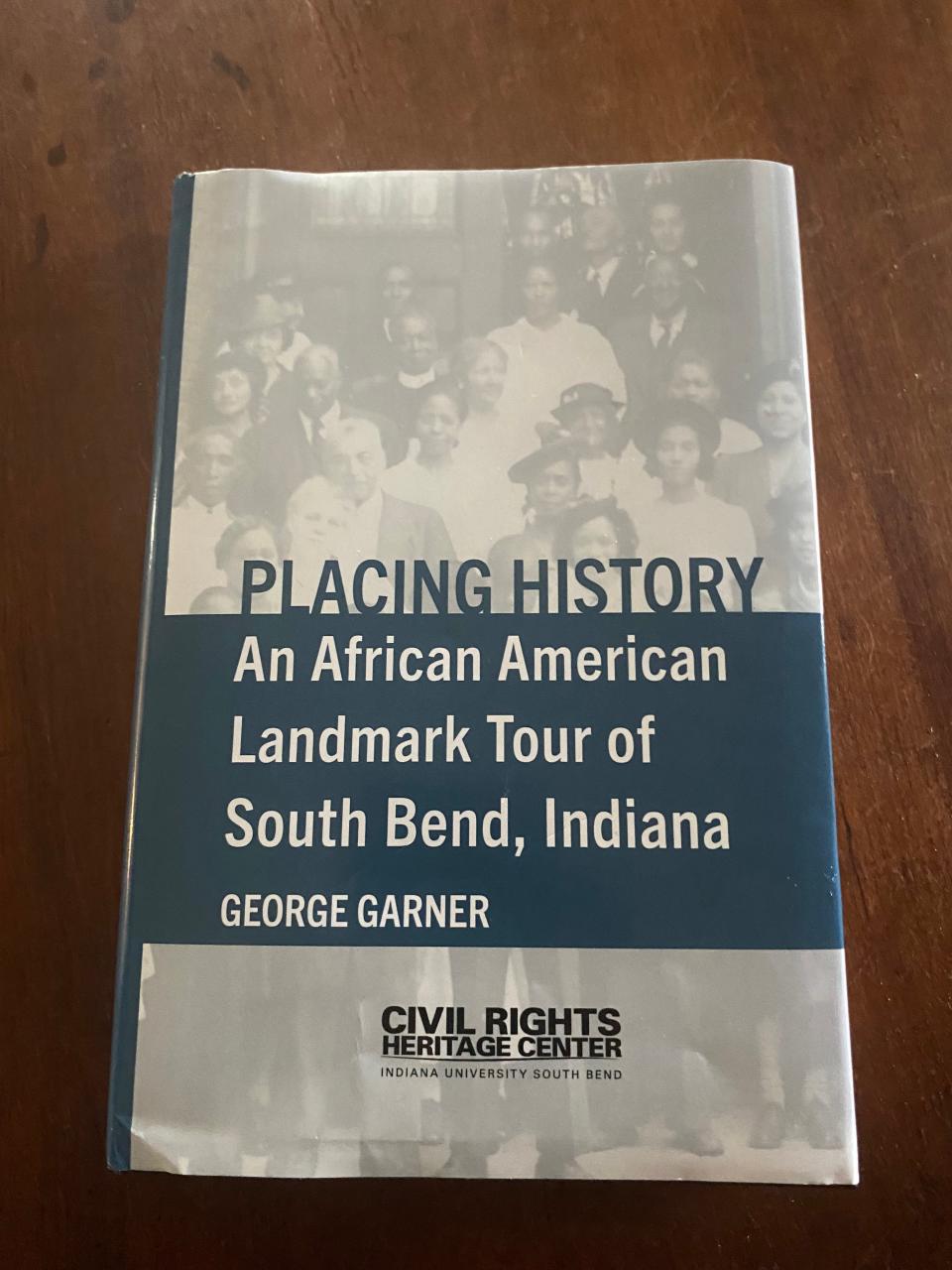

But I was most struck by the expressions of gratitude: Gratitude that this history had been painstakingly researched and respectfully presented by author George Garner, assistant director and curator at the Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center.

Many who gathered at the center for the event were grateful that stories about "The Lake," Hering House and Olivet African Methodist Episcopal Church, to name a few — places central to local African American history — were being acknowledged and shared.

One woman put it this way: "There is so much of our history … if it's not recorded, it will be lost. And people will only know about the urban uprisings that occurred. And there was a lot more to our community than urban uprisings. So thank you, George, for what you've done."

What Garner has done is present a rich and complex story that, as center director Darryl Heller put it, "hasn't been told nearly enough and not deeply enough."

"Placing History" is part of the refresh of the center's African American Landmark tour, which started in 2013. The book focuses on 10 of the 17 landmarks in the tour, including Linden School, a late-19th century school that was the first to hire African-American faculty and staff — but was shut down after a lawsuit alleged "intentional racial segregation and disinvestment."

Also included: The Engman Public Natatorium, which denied entry to African Americans who wanted to swim despite the "public" in its title — and is now the home of the Civil Rights Heritage Center.

Garner describes 'Placing History," the result of three years of research, writing and editing, as "a book about South Bend's African American landmarks … but it's so much more."

"This is a celebration of local Black history and the places where that history was made. It's an honest accounting of the challenges people in this community have faced, it's a collection of resistance to those challenges and the resilience of those who have long fought for justice."

Noting that "this work is not about me," Garner announced that he wouldn't be reading excerpts from his book. "This is about a community that I have come to call home after nearly 20 years. And I wanted to ensure that those community members are centered in this."

To do that, he played selected portions from the oral histories the center has collected and shared for two decades. These oral histories, Garner said, "deeply informed these pages … I think it's important that their voices are centered in this launch event."

It was riveting, including discussions about life on "The Lake," once one of the few areas in the city where African Americans could live, where the water was once pristine but became a dumping ground for industrial waste that remains at issue today. The streets were made of dirt, and city officials routinely ignored the needs of the community. But the story of The Lake is also one of close-knit neighborhoods where everyone looked out for one another and where "we were poor, but I didn't realize it because everybody was."

The stories were effective and affecting, perhaps in part because many of those speaking -— including local historian John Charles Bryant, descendent of the African American family that came to South Bend in 1858 — are no longer with us. Listening to Bryant talk about Olivet A.M.E., the city's oldest Black church and where his mother was the organist for decades, I couldn't help but think how happy he'd be about "Placing History." And he'd be thrilled that the book, which received federal grant support that paid for its initial print run, is free while supplies last, and also will be provided to local libraries for lending.

Garner had earlier told me of his hopes that the book will help inspire "deep community conversations about where we've been, what we've done and what we might need to do differently." He believes "with every fiber of my being" that we won't see meaningful change "unless and until we have an honest reconciliation with our history."

"That means difficult conversations, that means honest conversations, that means coming to terms with the reality of things that happened here."

It's a sentiment that runs counter to the voices that seek to erase parts of history and deny uncomfortable truths. It's a sentiment — and "Placing History" is a book — that should embraced.

Alesia I. Redding is The Tribune's audience engagement editor.

Where to find "Placing History"

Free print copies of the book are available at the Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center, while supplies last, one book per person. The book will also be available in the coming weeks at the St. Joseph County and Mishawaka-Penn-Harris public libraries and the Franklin D. Schurz Library. You can also download an e-book at aalt.iusb.edu, at https://sjcpl.org/ and with the Libby app.

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: "Placing History" spotlights landmarks in South Bend's Black history