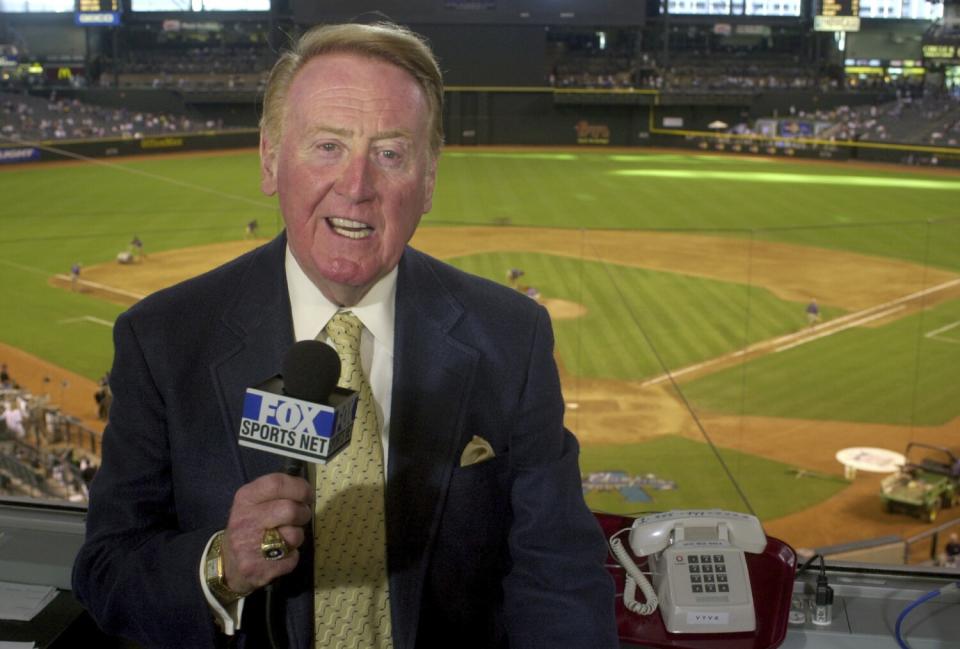

Column: Vaya con Dios, Vin Scully — a beacon of possibility for generations in L.A.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When legendary Los Angeles Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully passed away yesterday, I didn’t need to turn on the television, look at social media or hit up sports bars to know how much Southern California was mourning.

I just checked my text messages.

My brother sent over a slew of crying emojis. My cousin Vic admitted he had tears in his eyes while breaking the news to his wife. My cousin Plas — an Angels fan, somehow — added a video of someone pouring out whiskey from a flask, captioning it “RIP to the God.”

My good friend Bobby texted a black-and-white photo of Scully — nothing else. My sister Elsa, who owns a Yorkie named Vinny, told me to mention in anything I might write that Scully died on the feast day of Our Lady, Queen of Angels — the devotional title of the Virgin Mary that’s the namesake of Los Angeles. And my sister Alejandrina — for some reason, an Angels fan — countered with a link to a YouTube video of Scully, a devout Catholic, reciting the Rosary, which all us Arellano kids immediately listened to as we prayed for his soul.

That sobbing you’re hearing is hundreds of thousands of Latinos in Southern California mourning the loss of one of our own. Along with the late Kobe Bryant — another local sports legend with a huge Latino fan base — no other non-Latino Southern California luminary will ever evoke the same emotion among us.

Vin Scully was more than just the soundtrack of our lives. He was our lives.

He was the son of immigrants, like so many of us. He grew up working class, like too many of us. He overachieved, like all of us.

When the Dodgers relocated to Los Angeles, Scully left everything he knew for a foreign land. He arrived in a town that at that point was among the whitest big cities in the United States and saw it transform into the multicultural metropolis it is today, because of newcomers like him. He was there as five generations of my family — from my 99-year-old grandmother to the grandchildren of my cousins — established themselves in the Southland, all raised on his gospel.

Like so many Latinos, Scully came to a city brimming with possibility and made the most out of it. And he did it humbly, always hailing others before him, always preferring family over the spotlight.

From the start, he accepted Latinos from the start in a way too much of the rest of Los Angeles had to learn: as humans. He could’ve butchered the names of the many Latino players who passed through the franchise over the decades or on opposing teams, but he took the care to pronounce them right. He could’ve kept his Dodgers colleague, Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrín, at arm’s length, but embraced him like a brother and insisted the rest of the world acknowledge Jarrín’s brilliance when few would.

“He's not the Spanish Vin Scully,” Vinny told my editor, Hector Becerra, back in 2013. “He is what he is, Jaime Jarrín. He stands on his own two feet. He's a Hall of Fame announcer and a wonderful human being.”

Whenever he’d throw in a couple of Spanish phrases, your ears would perk up and you’d get a big grin on your face. When he deemed former Dodgers player Yasiel Puig a "wild horse," you would laugh because his gentle scolding was in the same tone as our grandparents would use on our wayward cousins. One of the many clips local television is playing right now is from 1990, when Fernando Valenzuela — another Dodgers Latino icon — threw a no-hitter. As the southpaw and his teammates celebrated, Scully exclaimed, “If you have a sombrero, throw it to the sky.”

Anyone else said it, you’d wince. But he was our red-headed tío.

He was the scaffold around which so many Latinos built their Southern California identities. His long, looping stories, delivered in that unforgettable troubadour voice, were like what our aunts and uncles might tell a group of us cousins deep into the night, drawing us in with history and triumphs and tragedies and connecting everyone to something bigger. Many of my peers learned English from Scully — as my jefe Hector once wrote, there was no better teacher outside of Warner Bros. cartoons.

Scully was even a rite of passage. At some point, you began to prefer Scully over Jarrín — not because one was better than the other, but because English was now the language you understood better.

I’ll always associate Scully with family, and not just because nearly all of my cousins and siblings are Dodgers fans. I’d watch games on television in the living room with my dad as a child, then did the same with my younger brother when I was a teen. When I became an adult, there were few things I loved better than to drive back from an assignment far away — Santa Barbara, Bakersfield, San Diego or Coachella — so I’d be able to listen to a Dodgers game in its entirety on AM radio, from his trademark opener, “It’s time for Dodgers baseball!” to whatever eloquent sign-off he might offer on a particular night, wherever I might be.

When Scully announced his final season back in 2016, my friends bugged me to see if maybe I could get them a private audience with him, even though I don’t cover sports, and I exclusively covered Orange County at the time.

They asked even though they knew I'd say no, because that's how much Scully meant to them. Instead, we reveled in the stories of my colleagues and friends who cover baseball, all of whom said the broadcaster was every bit the gentleman we imagined him to be.

That was all my friends needed.

We all mourn Scully today and for the rest of this baseball season the way we mourn the loss of our elders — the loss of an era, the loss of our innocence. The realization that life moves on, and that our heroes aren’t immortal — but that our time with them changed us for the better, and it's our time to carry on their legacy. We can't all be broadcasters, but we sure as heck can be good people like Scully.

Vaya con Dios, Vinny.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.