Column: A vigil for a long-ago plane crash shows how to remember the lives of the dead

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It has been a January of vigils for California.

For the Central Valley town of Goshen, after gunmen killed six members of a family, including a 16-year-old mother and her infant son.

For Monterey Park, where 11 people were killed at a dance studio just hours after the city's Lunar New Year celebration.

For Half Moon Bay, where a farmworker is accused of fatally shooting seven people, many of them his colleagues.

Last Friday evening in downtown Los Angeles, there were more commemorations for other deadly tragedies.

Mourners gathered outside the Los Angeles Police Department headquarters with candles and protest signs in memory of Tyre Nichols and Keenan Anderson, Black men who lost their lives after encounters with police officers in, respectively, Memphis, Tenn., and Los Angeles.

At the same time, half a mile up Main Street, a different kind of vigil was unfolding in a fourth-floor conference room at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, for a disaster that happened 75 years ago.

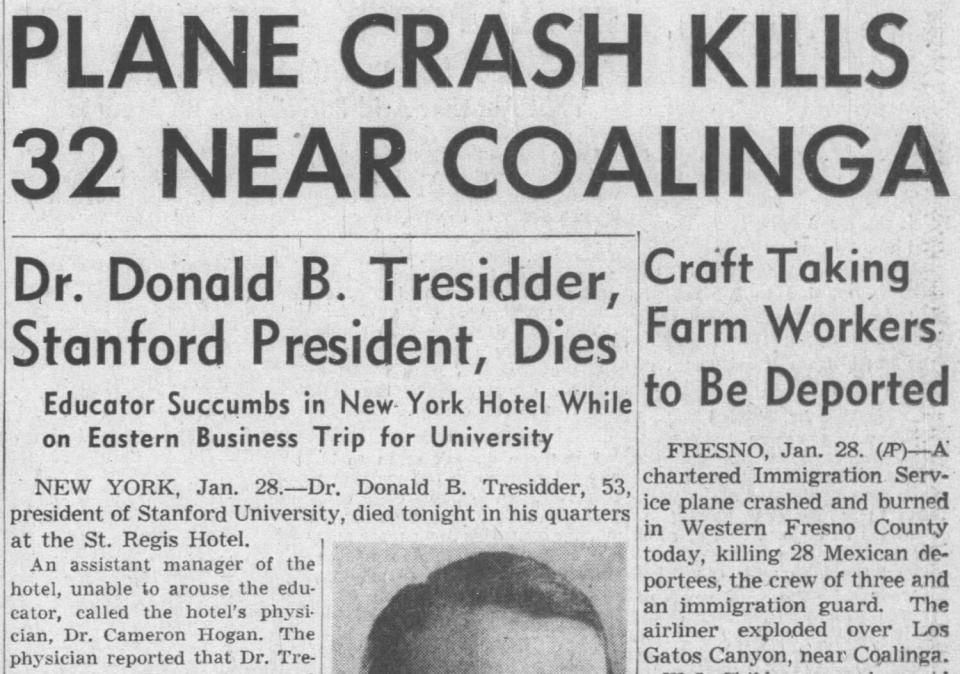

On Jan. 28, 1948, a plane crashed near Los Gatos Canyon 20 miles west of Coalinga, instantly killing all 32 people aboard. It was the worst aviation accident in California history at the time. While newspapers identified and ran portraits of the four white people who had been on the plane, 28 Mexican passengers were labeled only as “deportees” because the flight was a U.S. Immigration Services charter headed to Mexico.

The pilot, first officer, stewardess and an immigration official who were white received burials in their hometowns. The Mexicans — many of whom were part of the bracero program and working in the U.S. legally — were buried in a mass grave in Fresno, with a small plaque bearing none of their names.

This erasure so angered legendary folk singer Woody Guthrie that he wrote “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos),” a track covered by the likes of the Byrds, Dolly Parton, Bruce Springsteen and Tom Morello. It's an unsparing indictment of how Americans can blithely dismiss so much death when the deceased don't look like them.

It took until 2013 for a tombstone with the names of the so-called deportees to finally grace their mass grave.

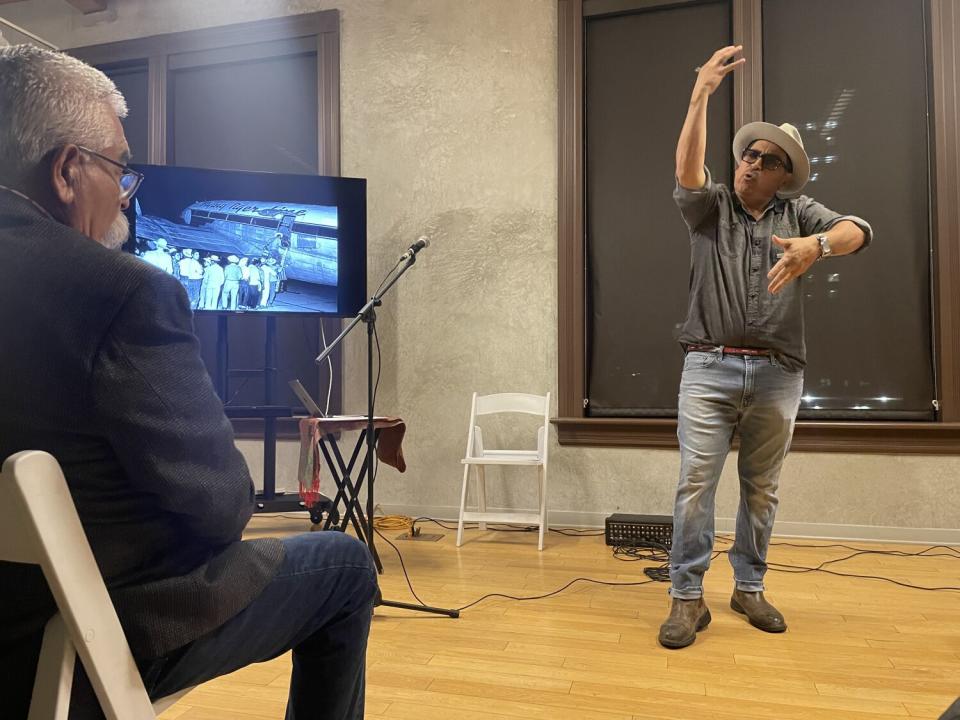

Author Tim Z. Hernandez, who helped raise money for the marker, has made it his life’s work to track down the victims' descendants — many of whom knew only that an ancestor had perished in a plane crash in the United States — and share the lost stories via a book, videos, lectures and more. The University of Texas at El Paso professor has connected with 13 families and vows not to stop until he has found them all.

At LA Plaza, Hernandez continued his decade-long vigil with a musical and spoken-word performance.

Gone are the days where strangers cried for a couple of weeks after a massacre, put up a monument, then left the family and friends of the deceased to their pain while the monument rusted or faded away. Now, we’re called to see each tragedy as a teachable moment and urged to remember victims for how they lived instead of how they died.

“They're never going to go away,” Hernandez said before his performance, referring to mass deaths involving migrants in California. “So I feel like as long as they happen, [the 1948 crash] teaches us things.”

Around 80 people packed into LA Plaza’s conference room. Behind them, in a small reception area, stood poster boards with names and photos of some of the 1948 crash victims.

Richard Montoya of Culture Clash began the event with a short monologue name-checking last week’s massacres and Nichols' death.

“These things are horrific,” Montoya said to murmurs of sad approval. “They shake us to our core.” He then praised Hernandez for “plant[ing] a flag firmly into that notion that we will account for each and every life.

“By gathering tonight,” he said, “you're holding onto these threads of sanity ... in the face of madness.”

Hernandez proceeded to tell the story of the plane crash, its victims, the ignominy of their erasure and his journey to resurrect their stories and share them with the world. Historical photos flashed behind him on a television. His partner, Ana Saldaña, offered musical interludes powered by her strong voice and comforting ukulele.

“Consider [this] an offer of light and love,” Hernandez said at one point, “in these difficult times.”

There were tears from the crowd, which included former Los Angeles Councilmember Gil Cedillo, whom Montoya teased for arriving late. But there was also laughter, as Hernandez acted out how he had to ask the macho father of a female cinematographer if she could accompany him on an interview. Applause when Hernandez offered clever couplets. Shouts of approval for Saldaña’s emotional rendition of “México Lindo y Querido,” the classic ranchera that asks the living to take the protagonist back to Mexico if he should die away from his home country.

As the evening proceeded, the victims of the 1948 crash came to life.

They were more than just farmworkers whose lives ended in a fiery calamity. They were baseball players. Artists. Fathers and sons and uncles. They planned to get married. They liked to sew.

Near the end, Hernandez invited Mike Rodriguez Jr., to join him. In 2015, the Fullerton resident and ethnic studies teacher reached out to Hernandez after hearing him on the public radio program "Latino USA." Rodriguez had always known that his Tía Maria — his father's aunt — had passed away in a plane crash in the United States. But his family didn’t know anything about the circumstances, nor her final resting place.

Maria Rodriguez Santana was indeed one of the victims of the Los Gatos Canyon crash.

Rodriguez and Hernandez recited the names of the dead, as Saldaña played a mournful melody on a wooden flute. After every name, the crowd chanted “presente” — present.

It was a moving presentation, a reminder that life always moves on — but we don’t have to forget those who leave us, or remember them only for the way that they left.

“They had a goal and purpose in life, and they had families that loved them,” said Patty Rodriguez, Mike's stepmother, during a brief question-and-answer session. “They deserve to be celebrated.”

John Martinez of Upland attended with his wife, Rosa. The two noted how the U.S. government still renders migrants nameless at our southern border, as people who die trying to cross and have no ID are buried in unmarked graves.

“Those families can’t even find them and make their peace,” he said. “Ceremonies like this allow healing.”

Afterward, we gathered again in front of the photos of some of the people whose names we had just invoked.

“Life is precious,” said playwright Josefina Lopez, whose father was a bracero. “We tell evil this way that every life matters. Their life impacted us.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.