When it comes to toxic algae, we're pretty much surrounded. What's that mean for our health?

In a region striped and spotted with waterways, harmful algae blooms are a fact of life. Yet we still know little about how they affect us, especially over time.

Scientists are working to change that.

In recent years, researchers from several Florida universities, nonprofits and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have started looking into their impacts with a variety of studies.

Earlier this week, a team from Florida Atlantic University’s Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing and Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute was in Cape Coral recruiting and testing volunteers for a first-of-its-kind study of the potential health impacts of exposure to the blooms. Florida Gulf Coast University researchers are helping with the collaborative project, which takes a multi-site approach. And, to sweeten the deal, volunteers can get up to $25 in gift cards for helping out.

Algae crisis: Airborne particles of toxic cyanobacteria can travel more than a mile inland, new FGCU study shows

"This is a very active and involved interprofessional collaborative effort," Principal Investigator Rebecca S. Koszalinski wrote in an email.

Co-principal investigator and FGCU marine science Professor Mike Parsons has been doing groundbreaking research into how far the toxins can travel by air (more than a mile) and how deeply they can penetrate the human body (all the way to the lungs' tiny air sacs). FAU Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute experts including Malcolm McFarland, another co-principal investigator are also pitching in, she wrote.

Scant data, but a few worrisome findings so far

Helping people stay healthy is the ultimate goal, says Koszalinski, an FAU associate professor.

The challenge: “We have minimal data on health outcomes related to human exposure, despite the prevalence and intensity of cyanobacterial blooms in South Florida.“

In order to protect those exposed, "Understanding short- and long-term health impacts and outcomes is crucial … By developing tools to measure concentrations of harmful algal bloom toxins in the environment and multiple human tissues, we will gain a better understanding of health-related outcomes and health care needs in Florida and elsewhere,” she said.

They're trying to cast a wide geographic net, recruiting participants from the greater Fort Myers/Cape Coral region in the southwest, Clewiston near Lake Okeechobee inland and Stuart to the east "in order to capture key areas of human exposure and a wide demographic population profile." said Koszalinski

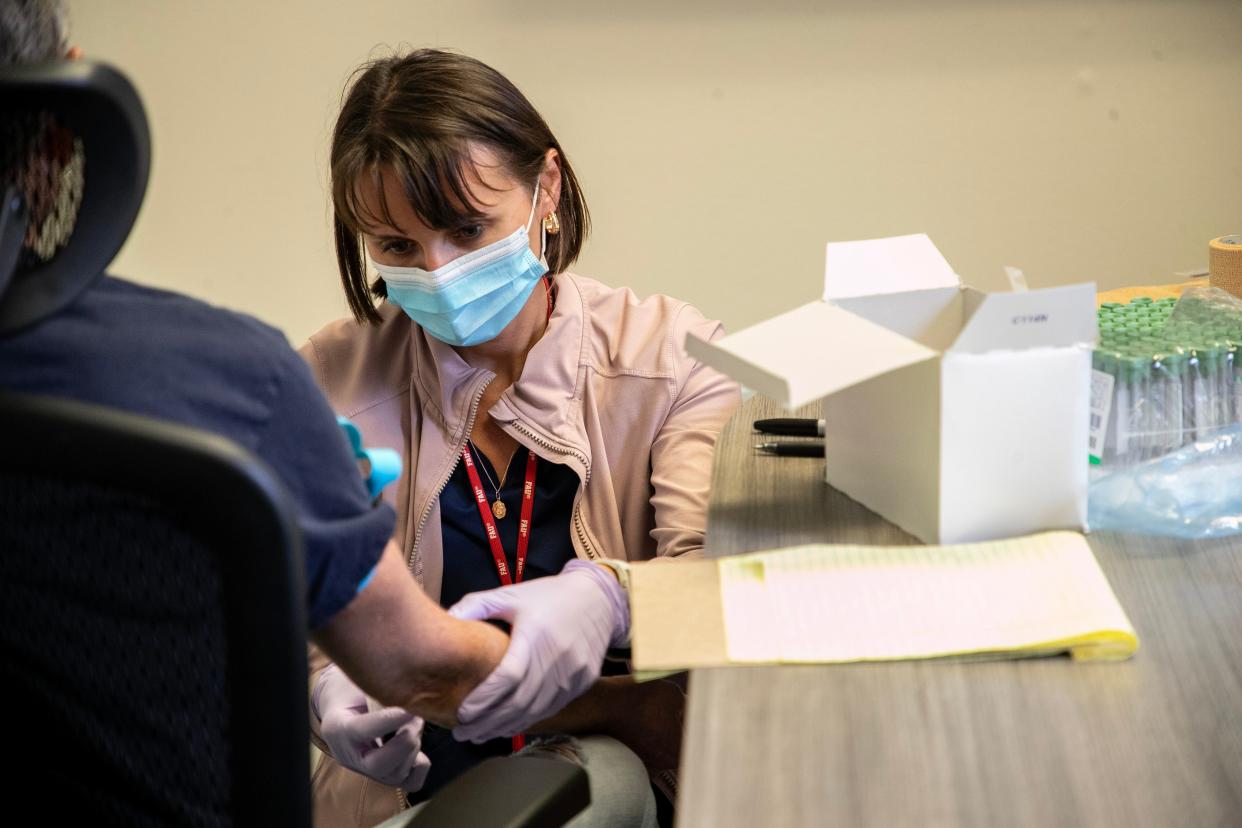

The research team set up camp at Cape Coral's Public Works Department Wednesday and Thursday, where they registered volunteers, then sampled their blood and urine and swiped their noses, COVID test-style. In fact, one thing researchers will be looking for is the potential effect of exposure to COVID-19, and whether there's a relationship between a history of COVID-19 infection and susceptibility to the effects of harmful algal blooms exposure. This study is the first to investigate that potential link, and whether people who've been infected are what Koszalinski calls a "new, sensitive subset of the population."

Volunteers will also be surveyed on potential routes, duration and types of exposure to blooms through their work and recreation. Researchers also will assess potential effects on people with pre-existing conditions like asthma and chronic gastrointestinal disorders with bloodwork including liver enzymes and renal markers,

Urine and blood analyses will be done in collaboration with the CDC, which is developing ways to detect emerging algal toxins in human tissues. The study also includes water and air sampling.

The data will become part of a permanent knowledge bank – what researchers call a bio-repository that includes a registry to store the data and samples to help with long-term studies and serve as a resource for researchers statewide.

Algae woes: From itchy eyes to dead dogs and brain damage

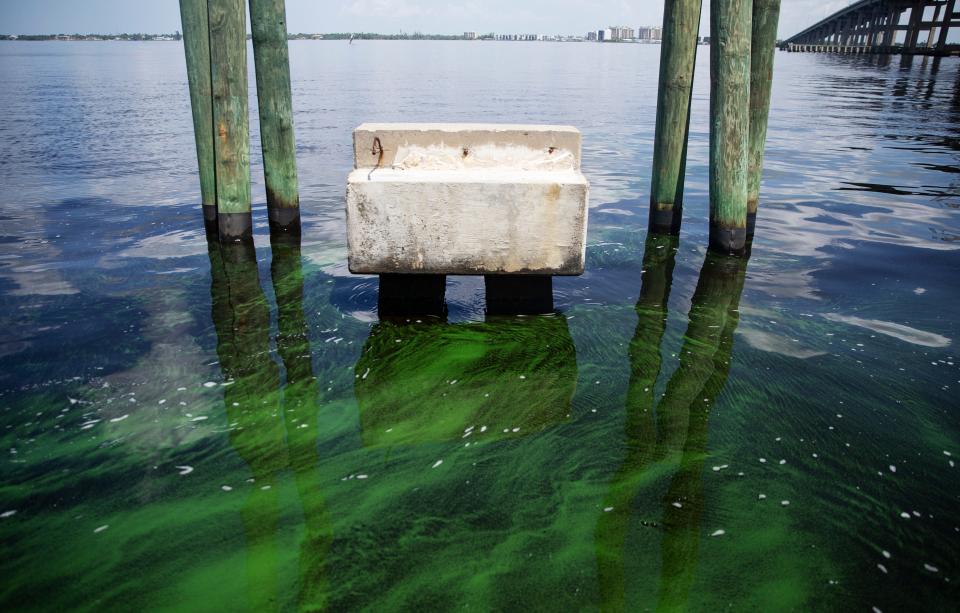

Though they can cause big problems, the organisms in question are microscopic: one-celled creatures commonly called blue-green algae or cyanobacteria, many species of which live in Southwest Florida fresh water. Though they’re critical to natural systems, when they multiply, they can be trouble. In saltwater, another microorganism, Karenia brevis, causes red tide, also considered harmful algae, though it's not the same as cyanobacteria.

Both occur naturally in the environment; both sometimes proliferate in huge "blooms" that can devastate wildlife populations, while keeping humans off the Caloosahatchee and Gulf beaches for more than 100 miles, from north of Sarasota to Marco Island.

Like red tide, some species of blue-green algae produce toxins that cause health problems in people and animals ranging from itchy eyes and sneezing to liver failure ‒ even death, if ingested in sufficient amounts.

What can trigger blooms? High temperatures, still conditions and water polluted with nitrogen and phosphorus. Those fertilizing elements encourage the blooms, according to the Environmental Protection Agency: “Nutrient pollution from human activities makes the problem worse, leading to more severe blooms that occur more often.”

Thanks to 19th- and 20th-century engineering, the Caloosahatchee is connected to a major source of nutrients: Lake Okeechobee, chronically plagued by algae blooms of its own. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which manages the lake, frequently releases its water to the river.

That acute exposure can make people sick and kill dogs is not in question. Longer-term effects are less clear, but algal toxins have been linked to a number of serious illness, including liver cancer and neurodegenerative diseases like ALS and Parkinson's that may take years after exposure to develop.

Hence, the proliferation of research, including this project, funded by a grant from the Florida Department of Health, says Koszalinski. "This latest study expands upon prior studies we have conducted in 2016, 2018 and previous FDOH studies from 2019 to 2020 and 2021 to 2022. We are in year five of our (harmful algal blooms) study and this year expands upon several previous years."

Filling information gaps, helping agencies make sound policies

This research will equip agencies and policy-makers with sound information to better protect the people they serve, Koszalinski says. "A science-based understanding of the risks associated with exposure to harmful algal blooms can assist regulators in making health-protective decisions and guiding mitigation efforts to reduce potential risks as well as the occurrence and spread of algal blooms. Importantly, measuring concentrations of HABs toxins in the environment and in multiple human tissues will fill an important data gap in understanding the effects of exposures."

The research has helped characterize the health effects associated with major bloom of blue-green algae:

In 2020, it demonstrated evidence of potentially liver-damaging algal toxins (called microcystins because they come from the algae genus Microcystis) in people's noses;

In 2022, it produced a novel approach for analysis;

In 2023, the team investigated self-reported symptom associated with activity patterns, contact with water, residential, recreational, and occupational exposure and

Most recently, it's found exposure to cyanobacteria at concentrations found during an algal bloom is associated with a diverse array of symptoms, and that breathing in toxins could be an important pathway for exposure.

For Koszalinski, it's a chance to to combine her interest in hands-on science and nursing with service. "I began as a bench scientist and as a nurse, I studied genomics at the NIH Summer Genetic Institute," she wroie in an email. " I am doing this work because important clinical research and bench science techniques inform health needs of our unique population.

"Floridians literally asked for research to better understand threats and outcomes of environmental changes. We are faithfully trying to answer their questions."

Though the team currently has an active group of volunteers, more are welcome says FAU spokeswoman Gisele Galoustian; the goal is to recruit 30 additional participants this year, she says. Ultimately, the team would like 150 volunteers.

Learn more, volunteer for the study

For more information or to participate in the research, call or text 561-297-4631, or email Rebecca Koszalinski at NurHAB@health.fau.edu. Community participants will receive up to $25 in gift cards as an incentive for participating in data collection activities each year.

This article originally appeared on Fort Myers News-Press: Harmful algae effects on health being researched, and you can help