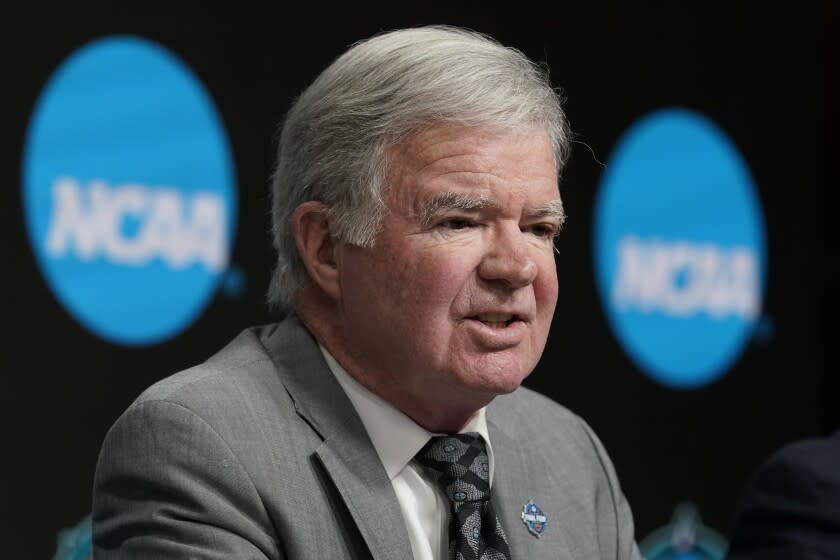

Commentary: Here is why Mark Emmert will be remembered as the guy who tanked the NCAA

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The greatest indictment of Mark Emmert’s 12-year run as NCAA president is the job description he leaves behind for his replacement:

Keep the haves among NCAA Division I schools from splitting away from the have-nots and creating their own governance model that allows for the pursuit of massive television revenues above all else and drops the pretense of college sports being an amateur enterprise at the highest level.

Convince those presidents and athletic directors at Power Five schools — many of which are now offering pay-for-play contracts disguised as name, image and likeness “collective” agreements — to continue to share the revenue pie from March Madness with all the little guys instead of starting their own men’s basketball postseason tournament that brings in at least $1 billion annually.

Assuming those predictable shifts occur in the future and the NCAA’s cash cow does graze toward greener pastures, save the Olympic and non-revenue sports that represent the authentic “student-athlete” experience at the bottom of Division I and throughout Division II and Division III, protecting thousands of educational opportunities for American youth who otherwise may not find their way to a college campus.

Back up the Title IX lip service with a genuine commitment to gender equity, avoiding embarrassments like the disparity between the bells and whistles at the 2021 men's and women's NCAA basketball tournaments.

Or how about developing policies that prioritize athletes’ physical and mental health? (Based on past NCAA behavior, this likely won’t be mentioned as a requirement, but it should be if the association wants to restore faith in its mission and validate its continued existence.)

Imagine the NCAA Board of Governors trying to sell candidates on taking on Emmert’s mess beyond the enticing $3-million salary. For anyone who’s qualified, which means they’re already rich and successful, the risk of wading into the stew of college leaders’ hypocrisy and swimming in it simply isn’t worth it.

Emmert always was the first person to remind you that the NCAA was not him and his crew in Indianapolis, but the universities that make up the membership. Those schools essentially formed a cartel that set the value of an athlete’s labor as the cost of an education — nothing more — and were able to avoid antitrust issues for decades because courts bought the notion that what made college sports as a product popular was that the players weren’t paid like professionals.

By the time Emmert took over in 2010, fewer and fewer Americans cared about that. Nearly two decades had passed since Chris Webber, the star of Michigan’s famed Fab Five, lamented to columnist Mitch Albom that he didn’t make a dime off the No. 4 jersey hanging in the window of a store as they walked through Ann Arbor.

Heck, Ed O’Bannon’s antitrust lawsuit against the NCAA that pushed for players to be able to profit from the use of their NILs was filed in 2009. Emmert, a university president at Louisiana State and Washington, was theoretically a smart man. He knew what he was walking into. His job description — or at least his interpretation of it — was to protect amateurism until its last breaths and absorb the public floggings that inevitably would come.

In that way, Emmert did his job. He got himself and his colleagues across higher education paid handsomely. Hundreds of new stadiums and ridiculous training facilities got erected with donor names slapped on the buildings for posterity. Emmert’s bosses — again, university presidents and chancellors — were happy enough with his performance to unanimously hand him another contract extension in April 2021.

But about a year later, on Tuesday afternoon, the NCAA sent a press release announcing Emmert would be stepping down, effective as soon as a replacement is found or by June 30, 2023.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise, if you’ve been following along. In June, the NCAA lost in the Supreme Court 9-0 in the Alston case, which did away with any compensation limits for athletes in regard to education-related benefits. That result neutered the NCAA, and the association punted on passing rules related to name, image and likeness, leaving it up to state laws or the schools themselves. The NCAA made it clear it did not want guarantees of NIL payments to be used as recruiting inducements, but it refused to legislate it or attempt enforcement, and so of course here we are not even a year later and we’re hearing about high school prospects agreeing to six- and seven-figure deals with schools’ newly formed collectives that are about to become the standard for programs that want to win big. And we haven’t even touched on the transfer portal yet.

Emmert is going to go down in history as the guy who tanked the NCAA. Of course, it actually was the presidents, but it won’t be remembered that way (again, Emmert performed the most important part of his job admirably from start to finish).

The NCAA as we have known it is on its death bed, but not because of what’s happened in the last year. In 2014, I covered the O’Bannon v. NCAA trial, which seemed like a historic ruling in favor of the players. Emmert and his bosses fought it, got a favorable appeal and buried their head back in the sand when they could have been proactive and granted players the right to make money from their fame.

Instead, Sen. Nancy Skinner had to file Senate Bill 206 five years later, outfoxing higher education leaders everywhere, not just Emmert, their whipping boy.

This year, we gained proof that college football and basketball players making money has not lessened the wonderful frenzy around fall Saturdays and March Madness. Thankfully, there will be no more NCAA fear mongering to that effect.

The NCAA will find a replacement for Emmert. He or she will come in talking about big reforms, but few will care enough to listen — a fitting legacy of their predecessor's practiced inertia.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.