Community Hero Valda Harris Montgomery is 'first-person witness' to civil rights history

Valda Harris Montgomery turned 8 years old the day that Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus.

Her home in Centennial Hill became a hub of activity as one of her neighbors, a kindly pastor and family friend named Martin Luther King, Jr., met with others there to plan the bus boycott. For more than a year her father, former Tuskegee Airman Richard Harris, organized rides for Black residents from his downtown drugstore while her mother, Vera Harris, drove anyone she could.

She was 13 when future U.S. Rep. John Lewis showed up on her doorstep in the middle of the night, beaten, bloody and looking for refuge. He and the other Freedom Riders who were working to integrate the interstate bus system had been ambushed by a white mob in Montgomery. She remembers Lewis walking through the hallway and collapsing in the kitchen.

As a child, Montgomery never got the chance to attend a public school in her hometown or see a white doctor. Those changes happened after her time. She was 16 and already training in nonviolent protest when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed, and she and others soon started working to integrate places like local movie theaters and lunch counters.

“Did we get the response we expected? Yes, we did,” Montgomery says. “But we knew how to conduct ourselves, and to be stoic and smile. You’re just not going to move out of that seat, period.”

She stops the conversation to make something clear: She’s not a historian. Montgomery is a scientist by training, so she’d prefer to only speak about what she has experienced. That just happens to be a lot.

Montgomery turns 75 in a few weeks. With her parents and many others of their generation gone, and racism and other forms of hatred now on the rise again globally, the retired teacher is being called on to speak about her experiences much more often. She’s opened her family home to the public while remaining a vocal advocate for the preservation of the Centennial Hill neighborhood where those events played out.

Those who know Montgomery say she’s thrown herself into that work with the same energy and passion she’s had throughout her decades shaping young minds as an educator in schools and universities here. For that lifetime of commitment to education and social change in her hometown, she has been named the Montgomery Advertiser Community Hero for November, an honor made possible by South University.

Longtime colleague Marilyn Watkins recently found herself staring at a photo of Montgomery and her mother that was taken while they were working with the Montgomery Area Council on Aging, one of the many causes Valda Montgomery has championed through the years.

“Hero is the right word for her,” Watkins says.

'Like your friend next door'

Montgomery was a professor at Alabama State University’s Department of Health Sciences when Watkins interviewed for a job there 17 years ago, and her presence made it hard to be stressed. “It just relaxed you. It was like your friend next door,” Watkins says. That calming approach extended to students, helping to grow the program.

“It brought in a caliber of student that knew they would be taken care of once they got here,” Watkins says.

Montgomery tried to resist becoming an educator because it was one of only a handful of roles Black women were allowed to have during her parents’ generation. But she was good at it, good enough that a trail of 'teacher of the year' awards followed her from the Maryland school system where she started her career to ASU. Beyond that, she quickly fell in love with science and its many disciplines and found it easy to share that love with her students and colleagues.

Huntingdon College professor Michele Olson built a 30-year friendship with Montgomery as they both sought and got doctorate degrees in physiology. But neither she nor Watkins knew about their friend’s history in the civil rights movement for years.

Watkins had watched Montgomery meet anger-inducing situations by smiling through them in silence. Bits and pieces of her past started to slip out in casual conversation. Olson only learned of Montgomery’s past during a routine teacher hiring process that required Montgomery to talk about outside interests. The pieces started to fit together.

“That also spoke to me about why she had a vision for students she was mentoring to go on and do more,” Olson says.

But Montgomery answers when asked. Through the years, the soft-spoken Montgomery has held leadership roles with the Friends of the Freedom Rides Museum as well as ASU’s National Center for the Study of Civil Rights and African American Studies. She was charged with helping organize fundraising galas for the latter, and donors responded.

“Because she said people ought to attend, she was able to make that ask,” says Janice Franklin, dean of library and learning resources at ASU.

Freedom Rides Museum site director Dorothy Walker says Montgomery continues to dedicate time, energy and resources locally, often quietly behind the scenes. “One of the things that I really admire about Valda is how engaged she is within the community, this community where she grew up,” Walker says.

'They want to learn'

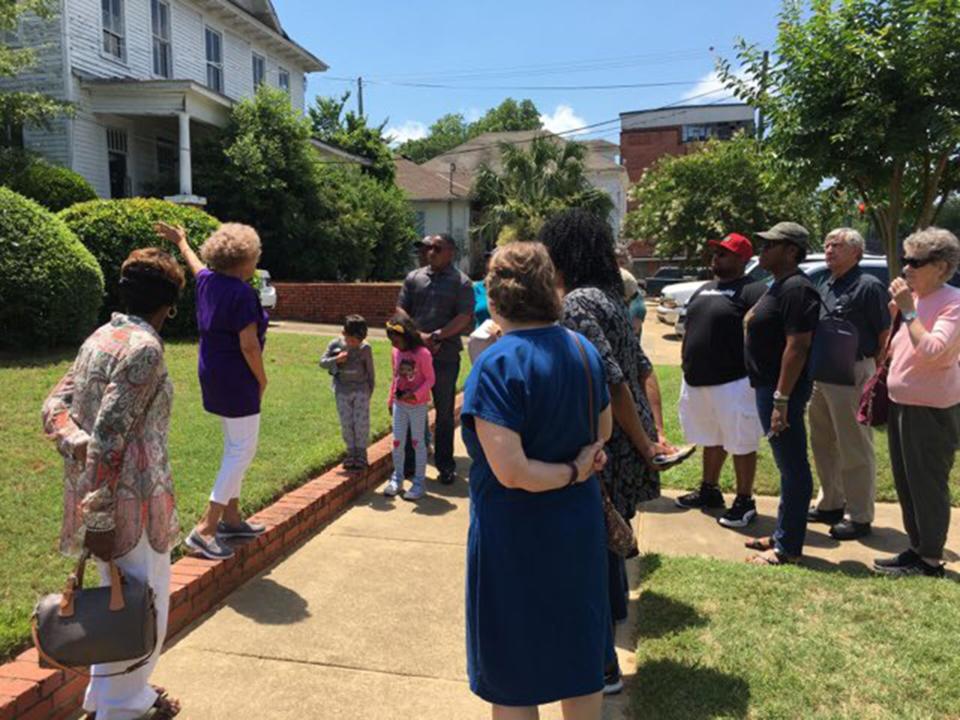

The door to the Harris House opens, and a group of history students are welcomed into the home by Montgomery. Inside, she shows them a rebuilt section of the lunch counter from her father’s drugstore where Black residents were allowed to eat. They stand in places where King and other rights leaders stood and eagerly listen while Montgomery tells the stories.

“What makes it more rich is to have Valda Montgomery describe what it was like as a first-person witness,” ASU history professor Howard Robinson says. “I think it makes the history come alive for them in ways that very few other experiences can.”

They keep coming, from all over. A group last week came from Yale. Other recent groups have traveled from Harvard, Stanford and Columbia. A group of ministers came to the home from institutions across the nation. Sometimes it’s just people who took a vacation and traveled here to learn more about American history so that they can better understand the nation today.

“Probably 98% of them are coming because they want to learn so they can see how to deal with what's going on nationwide,” Montgomery says. “We thank Bryan (Stevenson) and (the Equal Justice Initiative) because they put Montgomery on the map as far as tourism is concerned, and tourism is booming.

“When you stop and think about it, you've got vacation and you're spending your money to come and learn this trauma. But because of that interest I know, OK, we're on the right track.”

Throughout it all, Montgomery has worked to advocate for the preservation of the historic Centennial Hill neighborhood that includes the Harris House and King’s former parsonage. “All the efforts that she’s put into the community, it’s just like her father,” civil rights activist Doris Crenshaw says.

Montgomery says her pride in the neighborhood hasn’t wavered, even as some of its houses face an uncertain future and the Retirement Systems of Alabama builds an office on the corner. Her family has lived there since the 1870s, when her great-grandfather served as a Reconstruction-era state senator.

“It’s guess it’s just in my DNA,” she says, discussing her family history.

A blast of sound from across the street cuts her off, mid-sentence. The smile turned to stone-faced silence as she waits for it to end.

The smile returns. The story continues.

About Community Heroes Montgomery

Community Heroes Montgomery, sponsored by South University, profiles one person each month.

The 12 categories the Montgomery Advertiser will focus on: educator, health, business leader, military, youth, law enforcement, fire/EMT, nonprofit/community service, religious leader, senior volunteer, entertainment (arts/music) and athletics (such as a coach).

Do you know a Community Hero?

To nominate someone for Community Heroes Montgomery, email communityheroes@gannett.com. Please specify which category you are nominating for and your contact information.

Brad Harper covers business and local government for the Montgomery Advertiser. Contact him at bharper1@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: Community Hero Valda Harris Montgomery gives voice to history