Companies like Eli Lilly and E&J Gallo are landing in counties near Charlotte. Why there?

Dave Davis is competitive. And when North Carolina lost the Mercedes-Benz U.S. headquarters to Georgia in 2018, he dug in.

Davis, director of development at Concord-based Fortius Capital Partners, and colleague J. Harris Morrison III, Fortius’ founder, decided to take advantage of the potential for growth they saw in North Carolina.

“I hate to use a sports metaphor, but I know that when I lose something, it makes me attack it with a lot more velocity,” Davis said. “I’ll be a lot better prepared when the next opportunity comes around.”

National developers are identifying Charlotte’s nearby counties as welcoming sites for manufacturing development hubs.

Rowan County, 45 minutes outside Charlotte, has 22 million square feet of speculative property to prepare for incoming business. Neighboring Iredell County announced 11 million square feet in the past two years.

What are being referred to as “mega projects” or developments with more than $1 billion in investment, are on the rise, according to site selection experts. For instance, pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly is investing $1 billion in a Cabarrus County facility to manufacture obesity, diabetes and Alzheimer’s drugs.

Site selection experts and developers agree that North Carolina has a reputation as a business-friendly state. But with this added growth comes growing pains in infrastructure.

Companies are trying to simplify their supply chains post-pandemic, Davis said. He is seeing production returning to U.S. soil, increasing demand for manufacturing facilities. The Carolinas have available land and a skilled labor force, he said, which is attractive for manufacturers.

But the availability of land does not mean a ready-to-build industrial site.

Developers have to provide adequate infrastructure for utilities, said Didi Caldwell of Global Location Strategies, an industrial and manufacturing site selection firm in Greenville, South Carolina.

“A lot of good sites have been snapped up by projects already, so we’re struggling there,” she said.

‘No product, no project’

To create viable industrial sites, developers often build speculative properties that act like a blank canvas for expanding companies to choose from.

Fortius is a purely speculative developer, Davis said, which comes with its own set of challenges.

“It’s really hard to predict what companies are going to want from your property,” he said. “So through working with the economic development offices, you can try and figure out what is the best guess to put into the property.”

Speculative developers have to work backwards to include features they think a potential tenant may need, said Taylor Williams of Winston-Salem-based Williams Development Group.

Iredell County secured a deal with Walmart using a 1-million-square-foot speculative property, said Jen Bosser, CEO of the county’s economic development office.

Companies rarely have the time to wait for a property to be built when they need one, Williams said, which can take up to two years. If a business comes to an economic developer looking for property, they will usually have multiple product types readily available.

“No product, no project,” Williams said.

Site selectors work with companies looking for speculative properties, and know exactly what a property needs to be purchased.

Three necessities mentioned by site selection experts are labor, logistics and electric.

The cost of talent

Availability of land in a rural area needs to be balanced with the labor force. But labor does not have to come from inside the county.

Iredell County, for example, is surrounded by nine counties, Bosser said, so the jobs coming into the area can be filled by those inside and out of Iredell.

The skilled and semi-skilled labor force in the area provides a large and available labor pool, according to Williams. His firm developed Statesville Commerce Center, two speculative properties in Iredell County totaling 630,000 square feet.

Across the state line in Chester County, South Carolina, Global Location Strategies facilitated the $1.3 billion, 300-job deal with the Charlotte-based lithium battery manufacturer Albemarle Corp. in Richburg. Caldwell said the key to success is a small number of jobs so the county has enough of a population to fill them.

“For a rural county that is a huge win,” she said, “probably even bigger than a $1.3 billion project with 1,000 jobs because there’s not 1,000 employees that are sitting on the sidelines waiting to be employed.”

Ports, trains and automobiles

Between North Carolina’s rail system, highway network and access to ports, the state gives companies options when deciding how to export products.

Highways come up a lot when talking about site selection.

The Statesville development was chosen because of its proximity to Interstate 77, Williams said. Rodney Crider, CEO of Rowan County’s economic development office, said his county’s development is largely the result of the widening of Interstate 85. The I-85 corridor is the cornerstone of Davis’ business.

“The easiest way to move goods in a short distance is truck traffic,” Davis said.

Ports are the next necessity when it comes to exports. Davis said North Carolina has close access to three of the four strongest ports on the East Coast — Norfolk, Virginia, Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston. The largest port on the East Coast is the ports of New York and New Jersey.

Another method of transportation that may be making a comeback is rail.

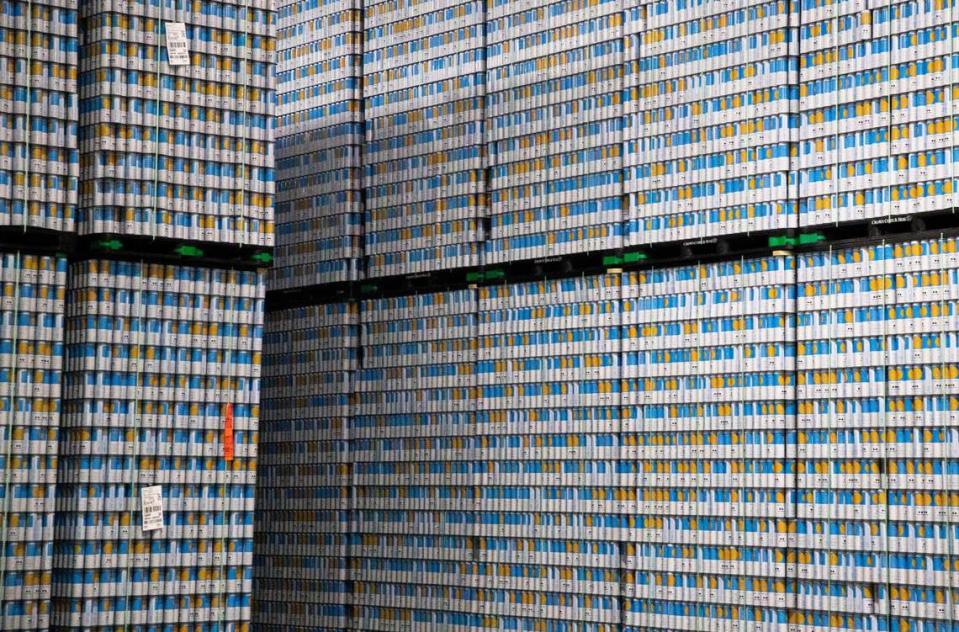

Rail is consistent, reliable and cost effective, Williams said. Chester County economic development office CEO Robert Long said the county’s rail lines helped secure its $423 million deal with E. & J. Gallo Winery last year. The winery uses the rail lines to move its products, incorporating rail tracks inside its warehouse.

Caldwell pointed out that rail helps companies comply with their environmental and social governance goals.

But new railroads are rarely built anymore, several experts said.

And building a rail spur, or an off-ramp section of a railroad line, can cost around $1 million, said Benton Blaine, a managing director at real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield.

A power struggle

As “mega projects” have increased, electric needs have too, Caldwell said.

Between 2008 to 2017, she said, Global Location Services announced 50 mega projects nationally. In the past five years, it announced 73. Many projects like these need more energy because they are physically larger, or because they are high-tech industries.

Five years ago, a large amount of energy for a project would be about four megawatts, which could power about 2,000 homes, Blaine said. Now, he has multiple projects using 40 megawatts, and one using 100 megawatts, which is a $15 million per year power bill.

Many of these projects want their own substation, which takes high voltage energy and makes it usable to consumers. Building one takes up to $30 million and about two and a half years to build, Blaine said.

As Charlotte’s ring counties try to keep up with the growth of projects and demand for their land, they still need to ensure that infrastructure keeps pace with that growth.

“Everybody wants to get a bite of the apple,” Davis said. “And to get that bite, we all have to work in collaboration to get there.”