After complaints about Pritzker’s Prisoner Review Board, advocates say it’s become too strict

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

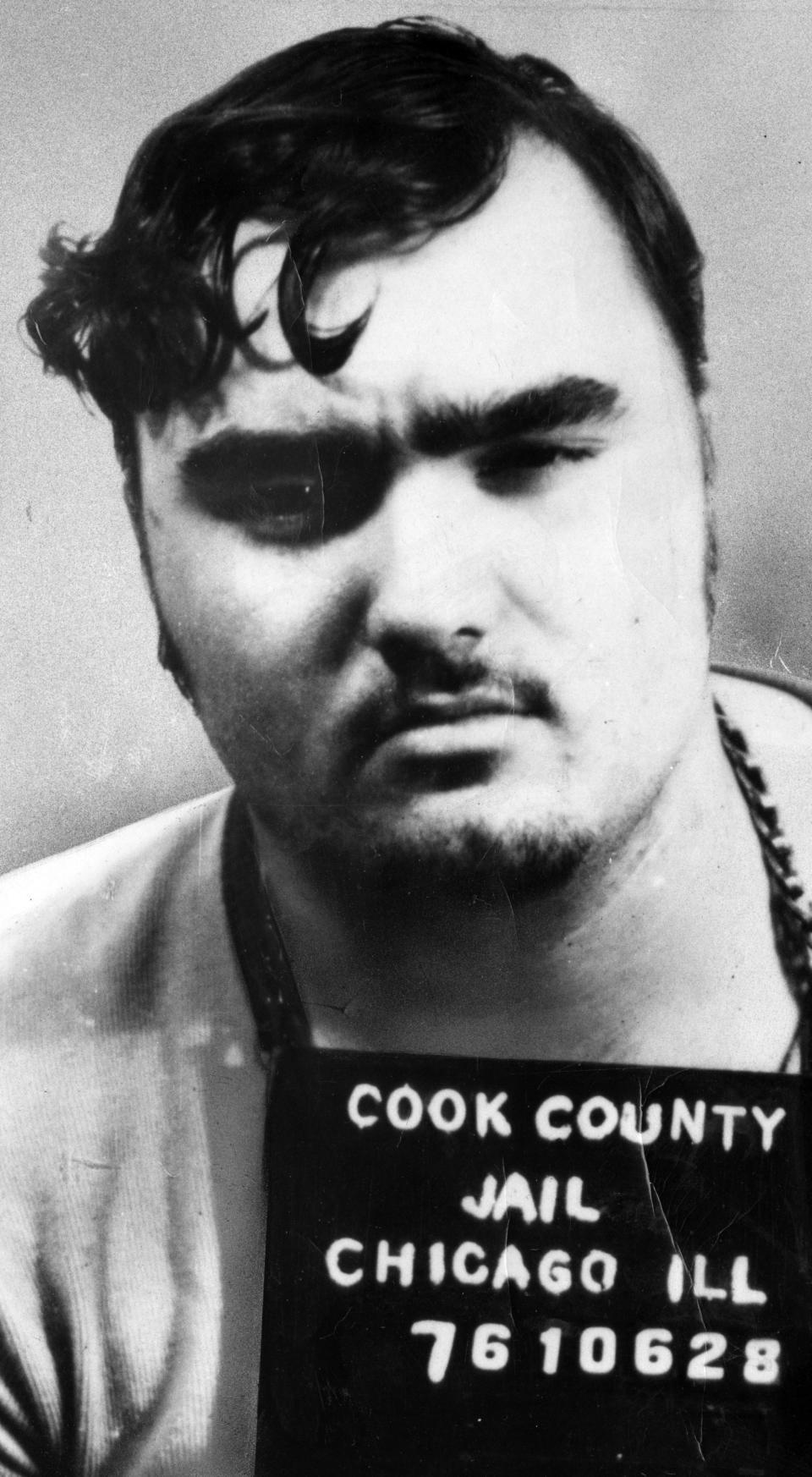

Ronnie Carrasquillo has been locked up for more than four decades for the 1976 murder of a Chicago police officer. Now 65, he’s come close to freedom on three occasions in recent years.

Carrasquillo went before the Illinois Prisoner Review Board in 2019, 2020, and 2021. Each time, he was narrowly denied parole by a vote of 7 to 6. In two of those cases, the seven votes were in favor of parole — but eight were needed.

But when Carrasquillo again went before the board in May, all of the board members who had been in his corner during the previous three hearings had been replaced. This time, Carrasquillo was denied parole by a vote of 8-1.

Some observers point to the Carrasquillo case as an example of a rightward shift the board has taken following criticism from Republican lawmakers who argued the board had become too lenient in granting parole to older people in prison who’ve been locked up for decades after being convicted of particularly heinous crimes.

The criticism was largely aimed at Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker, who appoints board members. The state Senate, even though it is controlled by Democrats, rejected two of Pritzker’s appointees, including one who had twice voted to parole Carrasquillo. (Board members can take their seats after being appointed but before being confirmed.)

The scrutiny came during a contentious reelection year in which Pritzker had to fend off attacks that he was soft on crime from Republicans who cited his support for criminal justice initiatives like the sweeping SAFE-T Act, which among other things did away with cash bail in Illinois.

The difference in the outcome of cases involving older inmates who had spent decades in prison in 2021, versus a similar number of cases during the following year and eight months, appears to bolster the argument that the board has tightened up on approving parole.

In the most recent time period, less than 15% of the 48 cases in that category that were reviewed by the board resulted in parole, according to records on the board’s website. That compares to slightly more than 40% of the 51 cases reviewed by the board in 2021.

The apparent shift in the board’s decision-making comes as Pritzker has become part of the national political conversation as a possible presidential contender, positioning himself as a prototype progressive on issues ranging from abortion rights to criminal justice reform.

Republicans who pushed back against some of Pritzker’s past appointments to the review board applaud the direction it has taken in recent months.

State Sen. Terri Bryant, a Republican from downstate Murphysboro, said the panel “is acting as they should,’' and in fact may be getting “a little too strict.”

“I think they might actually be a little gun shy, to tell you the truth, where maybe they should be a little bit more lenient than they have been in this last year,” Bryant said. “They have now gone kind of in the other direction. I’m happy about them going in the other direction so that they’re looking more closely. But they have to look at things on a case-by-case basis.”

Under state law, the board can have up to 15 members, with no more than eight from the same political party.

In December 2021, the board was made up of seven Democrats, six Republicans and one independent. In August, there were six Democrats, five Republicans and one independent on the board. Pritzker recently boosted the Democratic total to seven with the appointment of former state Sen. William Delgado of Chicago. Twelve of those 13 members are Pritzker appointments.

In a brief interview, the board’s chairman, Republican Donald Shelton, scoffed at the notion that politics are at play in the board’s actions, despite statements from conservative Republicans who say they believe board’s become more strict on granting parole.

“I couldn’t care less what any of them said,” said Shelton, a former Champaign police sergeant who has served on the board since 2012.

The board’s chief legal counsel, Kahalah Clay, said the panel “is an impartial, objective and independent board” and is not influenced by the governor’s office beyond his ability to appoint board members.

Pritzker spokesman Alex Gough said the governor has worked to recruit candidates for the board and blamed “politicized attacks on board members, from lawmakers in the Senate, during confirmation hearings, and in the press” for making that process more difficult.

But one former board member said her experience was that the board is not immune from the political climate.

Edith Crigler, a Democrat who stepped down as the board’s chairperson earlier this year, said Pritzker didn’t do enough to stand up for the board when it came under fire from Republicans, and also said she thinks the attacks have had an effect on the board’s work.

“The members on the board now are thinking more about how their vote is going to be viewed by the General Assembly, and especially by the (Senate) executive appointment committee, than the merit of the case,” said Crigler, a social worker who was appointed to the board in 2011 by then-Gov. Pat Quinn. “I’ve sat in the room with them and I’ve listened to them deliberate. And they are very, very conservative.”

Republican state Sen. Steve McClure was among those leading the charge to reject two of Pritzker’s review board appointments in early 2022. He took credit for convincing the Democratic-controlled Senate that some of the board’s decisions were problematic.

“People often ask what Republicans do in the Capitol when you don’t have many numbers,” McClure, of Springfield, said, citing the Democrats’ 40-19 advantage over Republicans in the Senate. “But this is probably our biggest accomplishment as Republicans, was turning around the PRB.”

People familiar with the board’s handling of cases involving older inmates say factors beyond political ideology can play into its decisions. In addition to considering the crime that put the person in prison and the person’s behavior once behind bars, criteria for granting parole include looking at how parole candidates have tried to better themselves and whether they’ll have a stable home environment if granted release.

But Christopher Mooney, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said the GOP’s “soft on crime” attacks against Pritzker form one of the most powerful arguments that can be made against a politician, and could well play a role in the governor’s thinking when it comes to board appointments.

“Pritzker knows that this is a loser, probably,” Mooney said. “And it’s an opportunity, and I know he’s been looking for these opportunities because I’ve heard this, for reaching out to the other side.”

The brunt of the criticism concerned a relatively small portion of the board’s workload, hearings that are primarily for aging prisoners who were given indeterminate sentences decades ago for serious crimes such as first-degree murder.

Most of those prisoners were incarcerated before 1978, the year Illinois limited parole in favor of an early-release system that makes prisoners convicted of certain crimes eligible to be freed once they’ve served at least 50% of their sentences.

In addition to these so-called “en banc” cases, an investigation by Injustice Watch and WBEZ-FM last month indicated the board has been especially tough in cases involving inmates seeking early release for medical reasons. The report revealed that the board has denied almost two-thirds of medical release requests from dying or disabled people in prison who were eligible to be released under the Joe Coleman Medical Release Act, which provides another avenue for the terminally ill to seek parole.

From January 2022, when the law took effect, until mid-August, the board granted 52 medical releases but denied 94 others, the news outlets reported.

Jennifer Soble, executive director of the Illinois Prison Project, which represents parole candidates pro bono, said many older parole-eligible people in prison have been hampered by not having legal representation when they go before the board.

“Without someone helping an incarcerated person navigate that system, it’s really hard for the PRB to get a truly comprehensive view, a truly comprehensive view of the incarcerated person’s trajectory, current situation and their hopes for the future,” said Soble, who has represented Carrasquillo.

Among the earlier board’s decisions that angered Senate Republicans were two that involved men convicted of killing police officers.

In two 8-4 votes in February 2021, the board agreed to parole for both Johnny Veal — convicted in the 1970 killings of Chicago police Officers Anthony Rizzato and Sgt. James Severin outside the Cabrini-Green housing complex — and Joseph Hurst — convicted in a 1967 shooting that left Chicago police Officer Herman Stallworth dead and another officer wounded.

Those cases and others led the Senate to take a harder look at Pritzker’s appointments. In March 2022, two of Pritzker appointees to the board, Jeff Mears and Eleanor Kaye Wilson, were rejected by the full Senate after getting grilled by Republicans before the Senate Executive Appointments Committee. The appointments of two other interim board members never made it to a Senate vote. Democrat Oreal James, resigned, while independent Max Cerda’s appointment was withdrawn by Pritzker.

Senate Republicans raised concerns over Mears’ votes in favor of parole for Zelma King, convicted of a 1967 triple murder, and Paula Sims, convicted in 1990 of killing her newborn child after a trial that included evidence indicating she killed another newborn four years earlier. Sims’ lawyer convinced the review board that her poor mental health likely played a role in her actions.

James and Wilson took heat for their votes to parole Veal and Hurst. Cerda, who has worked in the violence prevention field after earlier serving time in prison for a double murder and attempted murder committed when he was 16, was criticized for failing to recuse himself from voting on Carrasquillo’s parole — he voted yes — after revealing to the board that he knew Carrasquillo from when they were incarcerated, and even worked with him on a prison program.

At one point following the departures of James, Wilson, Mears and Cerda, concerns were raised by state officials over whether the board would have enough members to function. In the spring of 2022, the board was down to just eight members, five Republicans and three Democrats.

But since May 2022, Pritzker has appointed nine new board members, which along with some departures brought the panel’s membership to 13 as of mid-September.

In July 2022, the board voted 7-2 to deny parole to Veal’s co-defendant, George Knights, now 76.

Board members raised questions about a disciplinary infraction — Knights was sent to segregation for seven days in 2021 after being found with what the board described as “contraband.” Crigler, who voted in favor of his parole, described the object as “more of a needle than that of a knife” and Knights’ lawyer said it was made to score candy bars, according to board records.

Disciplinary issues also may have played a role in other cases where a larger majority of the board voted against parole.

Rudy Bell, 72, convicted in a 1977 murder, was denied parole in June by a 9-2 vote after narrowly missing a chance for freedom by votes of 7-6 in 2020 and 7-5 in 2021. Records show that a few months prior to the latest vote, he had been disciplined for being on the phone without authorization.

This past July, 71-year-old Eddie Pitts, convicted in a fatal 1976 stabbing of a Peoples Gas employee, was denied parole in a 10-1 decision after being denied release 5-3 last year. Records show board members in July raised concerns over a fight he got into in 2022 that resulted in another prisoner needing brain surgery. Pitts has dementia, according to the records, and his lawyer argued his actions were in self-defense.

Carrasquillo is in prison for the 1976 murder of Chicago police Officer Terrence Loftus in Logan Square. Carrasquillo was 18 at the time.

While the Cook County state’s attorney’s office did not oppose parole for Carrasquillo, representatives from the Chicago Police Department and its largest union, Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 7, showed up at the May hearing to oppose his release.

But a few months before the hearing, attorney Thomas Breen, who prosecuted the Carrasquillo case as a Cook County assistant state’s attorney, indicated to the board that Loftus’ killing wasn’t intentional, according to records from a February board meeting, and that “this was a difficult case with several witnesses that had been abused in the police station.”

“Mr. Thomas Breen stated that he is astounded that Mr. Carrasquillo hasn’t been paroled yet, and that he is one of those people that believe in redemption and stated that he doesn’t know what else he can do to show the Board,” records state.

According to Soble, Carrasquillo over the years has mentored and started programs for other people who were incarcerated.

Shelton, however, said the claim that the shooting was accidental was “resolved by the jury a long time ago, in addition to being implausible according to credible documentation and much prior testimony,” according to records.

Carrasquillo may be looking at another avenue for getting out of prison.

Last month, an Illinois Appellate Court panel vacated Carrasquillo’s sentence. The appellate court ruled that although Carrasquillo was not a juvenile at the time of the killing, circumstances of his upbringing and his maturity level at the time of the crime should allow him a “meaningful” opportunity for release.

Given the repeated denials of his requests for parole over 20 years, that route for getting out of prison “will never be ‘meaningful’ despite his demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation,” the court said in its ruling.

The case has been remanded to the circuit court for a new sentencing hearing.

The online version of this story was updated to reflect that Max Cerda’s appointment to the Prisoner Review Board was withdrawn by Pritzker.