This Complex of Temples and Gardens May Be NYC’s Best Secret

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is the latest in our series on underrated destinations, It's Still a Big World.

A silver lining to Staten Island’s comparative remoteness is that things that would almost certainly have been demolished decades or centuries ago in another borough are still there. Conference House, from around 1680, the Alice Austen House, whose oldest portions are from 1690, the Voorlezer House in Historic Richmond Town from not much later, and all sorts of other things. And the biggest survivor, the entirely undersung Sailors’ Snug Harbor.

If you haven’t heard of it you’re hardly alone–but you can fix that now. Sailors’ Snug Harbor contains a row of imitation Greek temples, the second-oldest theater in New York City, a walled Chinese garden originally constructed in Suzhou, a maritime museum wherein a flotilla of model ships are anchored, paintings by Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Jasper Cropsey, stained glass by John La Farge, a sculpture by Augustus Saint- Gaudens, a working farm, and much more. Its fans include Jacqueline Onassis and Whit Stillman, who largely shot his 2011 film Damsels in Distress there and attested in conversation, “I love Sailors’ Snug Harbor—pretty much everything about it from its history, creation and purpose to the extraordinary assembly of beautiful buildings.”

It’s all housed on the grounds of a former home for retired mariners amidst 84 largely green acres. It’s not really even hard to get to, save by New York City standards of extreme ease; 10 minutes by bus or Uber from the ferry terminal–or you can walk there in about 40 minutes, a strong excuse to pass by fine Victorian and especially Shingle-style homes in New Brighton en route. It’s a much better cause to go to sea than the Empire Outlets.

The feel of the campus is impressive and slightly surreal. The architectural critic Paul Goldberger described it this way in the New York Times:

“Snug Harbor has something of the feel of a campus, something of the feel of a small-town square. Indeed, these rows of classical temples, set side-by-side with tiny connecting structures recessed behind the grand facades, are initially perplexing because they fit into no pattern we recognize - they are lined up as if on a street, yet they are set in the landscape of a park. They seem at once to embrace the 19th-century tradition of picturesque design and, by virtue of their rigid linear order, to reject it.”

There’s an aura a little reminiscent of Governors Island, a place out of time, whose past isn’t initially easy to puzzle out. Snug Harbor is a bit farther along the tenanting path than Governors Island, so there’s more to do, and these tenants are a bit less aggressively bourgeois, so they’re less irritating. In other words, go.

Church, music hall, and fountain, Sailors’ Snug Harbor, Staten Island.

How did all of this get here?

Captain Robert Richard Randall, a prosperous mariner, willed the bulk of his wealth upon his death in 1801 to establishing a home for maintaining “aged, decrepit, and worn-out sailors.” Alexander Hamilton is believed to have written Randall’s will. Legal troubles (disputatious offspring, as usual) tied up the project for about 30 years, but that sort of delay is actively fortuitous when you own 24 acres of land in Greenwich Village. The goldmine of these real estate holdings enabled a shift of plan, to the purchase of 160 acres in Staten Island, where the institution opened in 1833.

The most consequential buildings were designed by Minard Lafever, (architect of numerous historic churches throughout New York) in Greek Revival style. Greek Revival styles were a go-to in the early U.S. for readymade associations of Athenian democracy, but generally not employed to house latter-day Jasons and Argonauts. There’s a very fine Italianate chapel designed by James Solomon, a Music Hall (the second-oldest in town after Carnegie Hall) and plenty else. Its landmarking designation reads, “A rare surviving example of urban planning, landscaping and buildings in the Greek Revival style, Sailors' Snug has no equal in scale, extent or quality in America.”

Snug Harbor swelled to considerable size over time. It contained 55 buildings and over 1,000 sailors at its 1880 peak. Not all of these were landmarks, but some were shocking. It featured a positively indulgent replica of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London (a lofty pulpit for a Reverend Mapples), complete with variegated marbles from Etruria, Siena, and Numidia–unfortunately lost to fire.

The Snug Harbor scheme was quite generous by the very low standards of 19th century retirement assistance: sailors were required to have five years of naval service for the US, or 10 for another country. There were no creedal or racial restrictions.

Captain Thomas Melville, youngest brother of Moby Dick author Herman, was governor of the campus from 1867 to 1884. Herman visited repeatedly.

The journalist and novelist Theodore Dreiser lived nearby for a time in Staten Island and wrote a piece on the institution for Ainslee’s Magazine in 1898, “When The Sails Are Furled: Sailor's Snug Harbor." He praised the place, writing, “The grounds are so ample and the buildings so large that the attention of every one is instantly taken.” He also wrote, “I doubt if a better conducted institution than this could be found.”

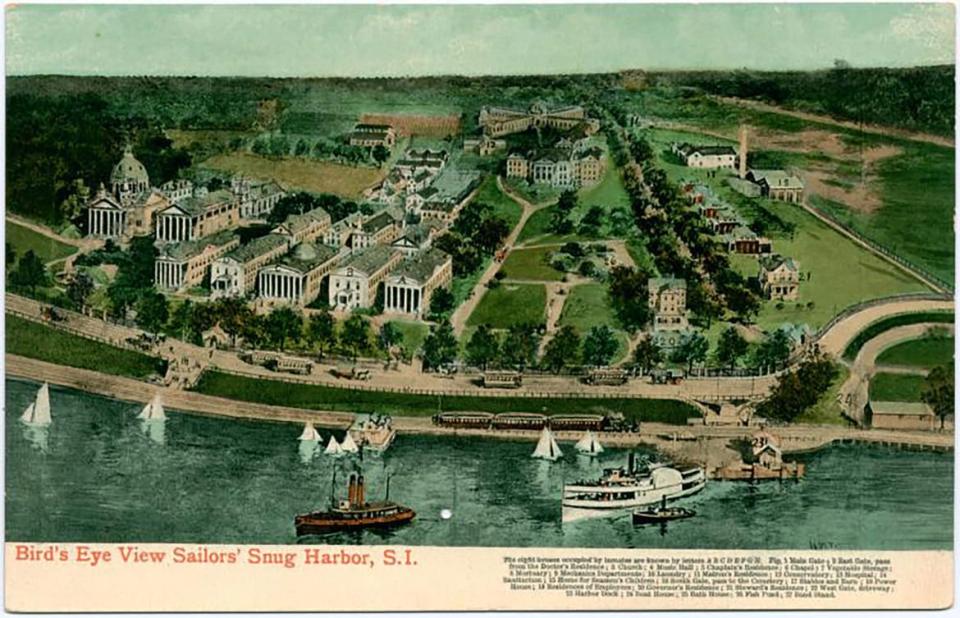

Bird’s-eye view, Sailors’ Snug Harbor, Staten Island.

The main note of fun and melancholy in Dreiser’s article is the elderly mariners themselves. “Though the surroundings are pastoral, the appearance of the inmates of this retreat, as well as their conversation, is of the sea, salty. Housed though they are for the remainder of their days on land, they are still sailors, vain of their service upon the great waters of the world and but littler tolerant of landlubbers in general. Dreiser reports the “pure cussedness” of some residents–and more. “So old and crotchety, most of them are.” Snug Harbor was theoretically dry but, “Not a few of them are given to sweating loudly, drinking frequently, snoring heavily on Sundays, and otherwise disporting themselves in droll and unsanctified ways.”

The number of residents dwindled over time, down to about 100 by the 1970s. Several buildings were demolished. The remaining sailors were relocated to a new facility in North Carolina. The city acquired the land in 1975 and Jaqueline Onassis was a prominent supporter of efforts to landmark portions of the complex. “The more attention that can be attracted to this lovely place the better,” she said on a 1976 visit, quoted in the New York Times.

Six of the buildings (and the interior of three) were among the first in New York City to be landmarked by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in the 1970s. Cultural institutions began to open in 1976, and you now have a full fleet of them to draw upon.

The Staten Island Museum has the highest profile of the complex’s tenants, and amidst the at-times exhaustive specialization of New York museums it’s refreshing to encounter a museum in which there’s a little bit of everything within a compact space. The Mastodon is just a few steps from the cicada collection, the Florentine Majolica just a few cases from the pipe stem from Burkina Faso.

The museum contains, as wall text explains, “one of the world’s largest collections of cicadas”, the work of one of the museum’s founders, William T. Davis. Cicadas figure prominently in a surprisingly engrossing current exhibit, “Magicicada”, by Jennifer Angus, which arranges cicadas in fanciful apothecary drawer displays (reading books and doing much else), jars, and a range of other settings.

Snug Harbor North Gate.

The art is eclectic but strong. There are Qing dynasty ceramics, Greek and Roman antiquities, but also a Raphael Soyer painting. A Nymphaeum–Baths of the Villa Aldobrandini at Rome Opus Civ by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, a taste of his exhaustive catalog of Roman decadence, awaits you.

A gallery of Staten Island art features some local plodders but a number of great pieces. Jasper Cropsey brings the Hudson River School treatment to the island in Looking Oceanward from Todt Hill, from days when there weren’t many home to impede the view. Elysian early vistas of the island remain always a shock (another from fellow Hudson River school artist Herman Feuchsel stands out) but there are several excellent pieces from the 20th century. Outsider artist Victor Joseph Gatto, a boxer in early life, shines with a suds-centered John L. Sullivan’s Beer Party at South Beach. Anthny Toney’s Klee-spirited Afternoon on a Hill abstracts away much more urbanized 1950s island hills to great effect. The collection isn’t all antiquity: A painting by Bosnian immigrant Amer Kobasliga depicting Hurricane Sandy damage on the island offers ample evidence that the local talent well remains full.

The Noble Maritime Collection holds all sorts of maritime art, with highlights by Swedish-American Gustav Romin’and marine artist Edward Moran. A transom window by American glassmaking master John LaFarge hangs within.

I don’t imagine you’ve seen many houseboat studios elsewhere in New York museums lately. There’s one here. John N. Noble was born in Paris, son of an artist, and raised in highbrow circuits, but worked on schooners and in marine salvage and found his Arles in the unlikely spot of the Port Johnston coal docks across the channel in Bayonne. He built a floating studio from salvaged parts and painted there for decades beginning in 1946. This artful wreck is now in permanent dry dock, awaiting your visit,

The building, which was once a sailors’ dormitory, features one room arranged as a bedroom would have been. There’s an exhibit on Kate Walker, the keeper of the Robbins Reef lighthouse north of Staten Island from 1890 to 1919, who took over the position after her husband died and rescued some 50 mariners from drowning over this span.

The museum contains ship models of antique and recent make, depicting all sorts of ages of sail and steam, from the Bonhomme Richard to HMS Victory to La Couronne from Richelieu’s French navy. Tools of the trade also abound, from stadimeters (for measuring the distance between ships, news to me) to sextants to octants and onwards.

A former writing room is topped with a trompe l’oeil ceiling mural of a glasshouse roof with hints of the South Seas.

A maritime library offers a wide-ranging selection of nautical books, from Jules Verne to Jane’s Guides to ocean liner histories; all of the armchairs and desks were empty upon my visit.

Other attractions include a children’s museum, lively from the exterior. The Music Hall is currently being renovated and expanded but held an assortment of concerts in the past, and will host more. The Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art is currently closed but past exhibitions and the structure seem a strong attraction, with a large dome and painted nautical ornaments by Charles Berry inside. Other arts organizations hold classes in a variety of buildings.

Just walking around the remainder is well worth it; a row of Second Empire cottages by Richard P. Smyth especially warrant inspection. There’s a replica of a Saint-Gaudens statue of Captain Randall (the original is in the Newhouse building), and a recast J.W. Fiske statue of Neptune. More contemporary sculptures are dappled around.

Gardens are a prime attraction, none more so than the superlatively placid Chinese Scholars Garden. The garden was originally built in Suzhou and then disassembled and shipped to Snug Harbor, where a team of 40 Chinese artisans reassembled it, to open in 1999. The main structure is walled, but includes numerous nooks accessed through gates in the shape of banana leaves, gourds, or keyholes. There are bat-shaped door pulls. The structure was built without nails or glue using traditional Ming dynasty methods, and frames ponds and waterfalls, and sculptural rock arrangements. Flowering plum, saucer magnolia, peach, and eastern white pine trees, and winter jasmine and bamboo plants can be found throughout. There is a “knowing fish pavilion” (I don’t know) and “the garden of poetic pleasures” (absolutely).

The grounds also include a Tuscan garden, English-styled white gardens inspired by Vita Sackville-West’s monochromatic Sissinghurst gardens, a rose garden, a Hornbeam allee, and a castle-walled secret garden, inspired by you know what, closed on my visit but looking great in photos. Wetlands, trails, a sailors’ cemetery, and a working farm all can be found elsewhere on the complex.

The campus makes occasional screen appearances, on Law and Order SVU, Gotham, and Madam Secretary. Its top billing occurred in Whit Stillman’s 2011 film Damsels in Distress, in which it stood in for a fictional Seven Oaks College. The director of Metropolitan, Last Days of Disco, and Love and Friendship was seeking the right setting.

Snug Harbor rapidly impressed, he explains in an interview. “It’s my favorite architecture. It’s one of the greatest collections of Greek Revival architecture in America. It’s like a row of temples … I used as much of it as I could. It’s like certain people when they eat the chicken they eat the gizzards and the neck and everything.”

Snug Harbor 19th-century Greek Revival structure on Temple Row.

The production used a number of buildings that aren’t open to the public (you can find on screen). He recalled a “stupid story” alleging his disappearance from a day of production; he was actually peering around additional interiors on the campus. They couldn’t use the music hall but he declared it, “absolutely terrific.”

The location is unusual in that it sits across from a highly industrial stretch of New Jersey visible across the main lawn; Stillman simply never shot that angle. “If you look the other way you can see these enormous ships. It was fun doing that cheat because we made it look like a tranquil quadrangle but it’s actually opposite this busy shipping channel.”

The containerized present and the sails of the past are all visible at Snug Harbor, and you don’t need to retire to drop in. I’m not going to be so foolish as to declare this the most unusual cultural complex in the city of New York, but it’s certainly a surprise from about any vantage, and about the easiest “day trip” you could mount.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.