The complex way California pays 300,000 state workers each month, and how new raises are added

If California’s state payroll system were a person, it would be nearing its 70th birthday this year.

Like some septuagenarians, the payroll system periodically finds itself struggling to keep pace in the modern age. Unions, workers and lawmakers alike have taken turns over the years bashing the system for delays in payroll changes and occasional pay mistakes. In the last six years, two different state worker unions have either taken or threatened legal action against the state due to delayed raises.

Still, despite the burden of a cumbersome and outdated apparatus, the State Controller’s Office together with departmental human resources departments and CalHR manage to deliver timely and correct paychecks to the vast majority of state workers every month — nothing short of a small miracle.

Back in the 1950s when the system was first developed, the state employed about 40% fewer workers and didn’t engage in collective bargaining until the late 1970s. Today, nearly 300,000 workers across state civil service and the California State University and University of California systems rely on the payroll system for their paychecks.

State controllers have envisioned a complete overhaul of the system since at least 1999, when the Legislature dedicated $1 million to the project. A previous modernization attempt was scrapped by former Controller John Chiang after a failed roll-out to a small number of employees in 2013. The state ended up settling a lawsuit in 2016 and received a $59 million refund from the vendor.

The latest reinvention effort, branded as the California State Payroll System Project, started in 2016 and won’t be completed until at least 2028. Under the new system, state workers could be paid on a more typical bi-weekly basis rather than once a month — a shift that would give employees more financial flexibility as they juggle budgets and combat inflation. Budget documents from this year show that the state has authorized more than $200 million in spending for the overhaul, and the project’s total estimated cost hovers around $715.5 million.

Trying to figure out how the aging payroll system operates is a challenging endeavor. Monique Langer, who oversees public affairs for the Controller’s Office, admitted that even she didn’t entirely understand the payroll process.

“Payroll isn’t just keying something in and printing the check,” she told The Sacramento Bee in August. “These transactions and personnel are a vital part of the payroll process,” she said, “but all state agencies and many divisions within the State Controller’s Office work together to make payday possible.”

Timecard to paycheck: How do state workers get paid?

The payroll process starts with employees’ timecards. Each department can choose how it tracks employees’ hours, and in large departments such as the Department of General Services, different employees use different methods.

Some workers track their attendance using an electronic timekeeping tool, such as Tempo, which 22 state departments currently use, according to the company’s website. Some still send in a PDF known as an STD 634 to their supervisors each pay period with a record of any leave taken or extra hours worked. And some workers still use physical punch cards to track their hours.

“CalHR does not currently dictate the software (or manual process) that departments must use for collecting time sheet information,” said CalHR spokesperson Camille Travis. “Departments have discretion and use a variety of processes to arrive at the same necessary information for payroll.”

It’s unclear how CalHR and the Controller’s Office manage to synchronize each of the department’s time sheet formats into a universally readable version.

Around the 22nd of each month, departments are required to submit their time and attendance data to the Controller’s Office so it can start preparing the rolls.

The vast majority of state employees are paid once a month and on a “negative” basis. Employees are presumed to have worked a regular schedule unless the Controller’s Office receives attendance data from the department that shows otherwise.

The controller then prepares paychecks and direct deposit orders that it sends to departments and agencies around the 27th. Departmental human resources staff then check to make sure an employee is being paid for the correct number of hours. If there’s a discrepancy between the worker’s reported attendance and the amount in the paycheck, HR staff will use a manual form to note the mismatch.

Any paychecks that are for the correct amount or less than what the employee should be owed are sent out. Checks that are written for too much money are sent back to the controller, redeposited and then reissued. The state “provides for salary advances if legally payable salary warrants are delayed,” according to the Payroll Procedures Manual.

Some employees are paid on a “positive” basis, meaning their departments must verify their attendance using time sheet information before the controller will issue their paychecks.

“When submitted timely, positive pay is expected to be issued by the 15th of each month,” said Langer.

Who cuts the state worker checks?

Most state workers receive their paychecks directly in their bank accounts through direct deposit. But for 13% of the state workforce — or a little more than 1 in 10 state employees — paychecks still come the old-fashioned way.

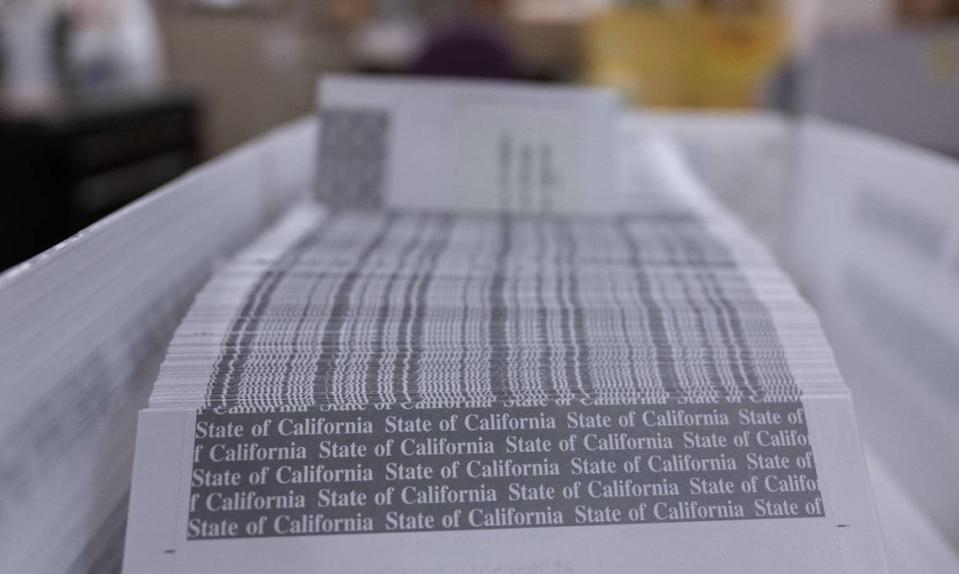

Environmental scientist Lexi Thornton counts herself among those who still earn paper checks. Each payday, a “fancy cardboard envelope” embossed with State Controller Malia Cohen’s name appears at Thornton’s front door in Chico. In her four months working for CalRecycle, Thornton has never had an issue with a late paycheck. She even gets paid a day or two before her colleagues who receive their checks through direct deposit.

“I do feel like I’m itching to get it because it has been a month,” she said. “But I think it all depends on your relationship with money.”

But when do the checks actually get cut? That begins usually on the 24th of the month as members of the Administration and Disbursements division at the Controller’s Office take on the printing of the state’s monthly master payroll.

These are the checks that workers like Thornton will receive on the last day of the month — one day ahead of those with direct deposit.

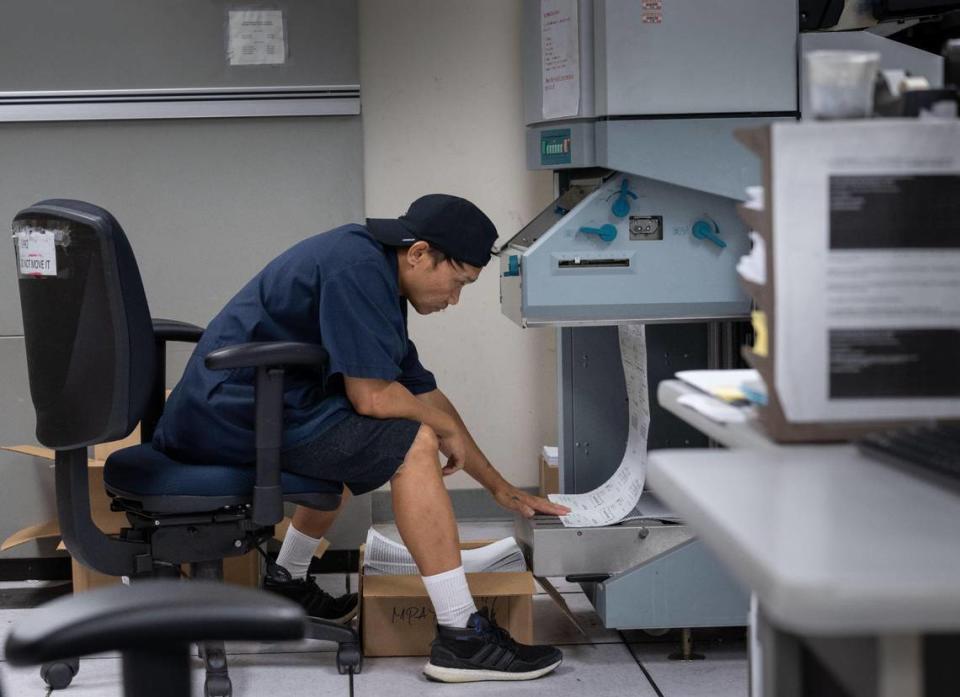

In a printing room, IT technician Erwin Corpuz inspects the printer’s rollers and loads a stack of continuous-feed computer paper on the machine’s right end.

The device whirrs to life. Quickly, it slurps up the blank pages. The paper whizzes through in one unbroken sheet until it comes out the other side, splashed with state workers’ names, addresses and the amount of money they’re owed for the previous month. The pages emerge like freshly rolled pasta and accordion down into a neat pile on the machine’s left end.

Every few minutes, the machine pauses, lowers and presses the newly printed payroll warrants until they’re folded flat. Corpuz carefully takes a knife and cuts a stack of paper free. He slides them into a cardboard box and places them on a cart.

These days, Corpuz says monthly payroll only fills about six or seven of those boxes. But earlier in his now-18-year career with the Controller’s Office, before the widespread adoption of direct deposit, he would often print closer to 60 boxes worth of checks.

The next stop for the newly printed checks is the mailroom, just down the hall from the printing center. There, the boxes that Corpuz packed are ripped open by Amanda Ruby, a mail machine supervisor, and her team of operators. They feed the ribbon of paper straight out of the box and into another machine that slices and pressure-seals the checks into the little packets that workers await in the mail. Ruby said it takes between six to 10 hours to seal all the checks from monthly payroll.

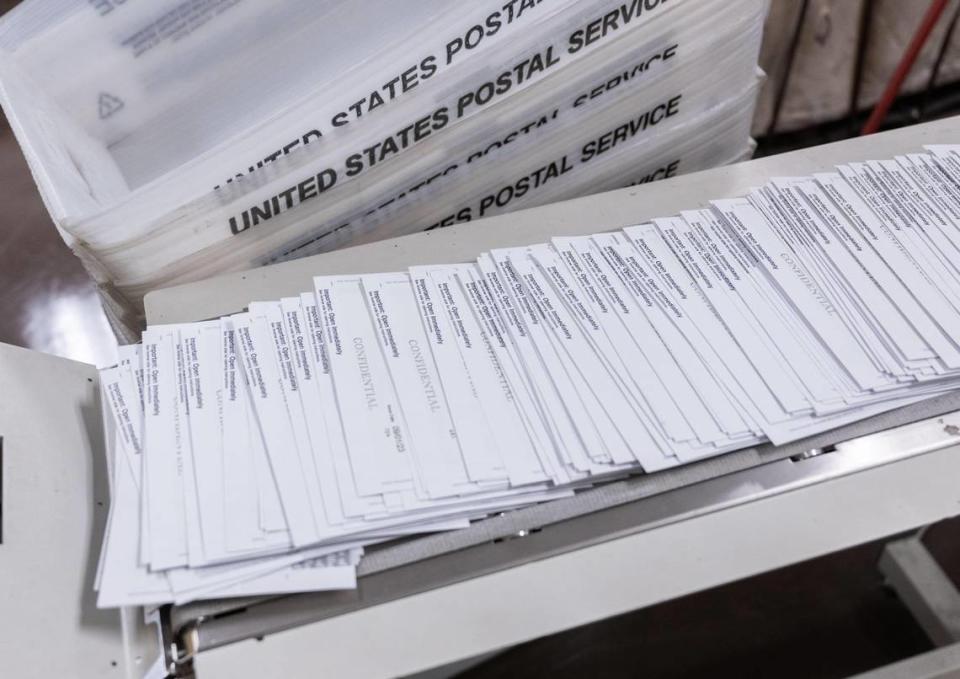

Finally, before the mail goes out, another team presorts the envelopes by ZIP code so the department earns discounted rates from the U.S. Postal Service.

Ernest Williams, a 23-year veteran mailing machine operator, loads the letters into a machine that rapidly reads the address and spits them out into bins by ZIP code. Chelsea Jacobs, a mailing machine supervisor, darts back and forth transferring the newly sorted letters into Postal Service mailing bins lined up on racks behind the sorter.

Departments then distribute the checks to their workers. Local offices send couriers to pick up the paychecks from the controller’s Sacramento facility, while some checks are mailed out directly from the front office.

Thornton said she would consider signing up for direct deposit in the future, and she thought she filled out the necessary paperwork during her onboarding process. She’s not in an immediate hurry to go paperless, though.

“I guess I haven’t been in a rush because it has always been right on time, and with mobile banking, I can just immediately take it in the house and deposit it with my phone.”

How do contract raises and benefits appear in workers’ paychecks?

The majority of California’s nearly 240,000 state workers are expected to end the summer with new union contracts and promised pay increases.

Thirteen of the state’s 21 bargaining units entered negotiations with the state for new deals, and as union members and the Legislature finished authorizing the agreements, workers might wonder how and when they’ll see raises in their paychecks.

The state’s payroll system has a rocky history of implementing contract raises. The state’s operating engineers’ union filed a grievance over late pay raises in 2017, and the union representing state attorneys threatened to sue for similar delays in 2019.

Once a new contract is ratified, CalHR drafts a formal “Pay Letter” to the Controller’s Office with instructions for how to adjust worker pay, department spokesperson Camille Travis said.

The letter describes to the Controller’s Office how much to adjust worker pay, either by percent or dollar amount. It also identifies which bargaining units are affected, denotes any classifications or employees who are excluded from the change and provides the date the pay adjustment should be implemented.

The controller’s staff then identifies the employees eligible for raises, programs the payroll system with the new rates and runs a test. Finally, the controller writes up a report about how the pay raise will be processed. For widespread adjustments, such as unit-wide general salary increases, the controller can program the change en masse. But individual departments’ HR shops are usually responsible for manually keying in pay adjustments that affect smaller groups of employees. CalHR then includes that information in a final published Pay Letter.

If departments must make the changes themselves, the controller will provide a separate letter with detailed instructions on how to make the change.

“Collaboration and cross-checking between multiple divisions within CalHR ensure that pay changes are not missed and they are issued correctly,” Travis said.

A Sacramento Bee analysis of employee pay data from the Controller’s Office found that most workers whose contracts entitled them to general salary increases on July 1 of this year received those raises on time. It’s not clear how long CalHR and the Controller’s Office will need to process all the newly negotiated pay raises from this summer, especially since many of them require backdating to July 1.

“The time to implement any bargained agreement depends on a number of factors,” said Travis, the CalHR spokesperson, “including but not limited to, complexity of the change, timing of the full ratification of the bargained change, volume of other work required simultaneously for other Tentative Agreements with other units, etc.”

The Bee’s Phillip Reese contributed to this report.