A complicated love story: Author Carlos Bulosan’s critique of America gave Filipino migrants a voice

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

ALLOS, THE PROTAGONIST of Carlos Bulosan’s 1946 autobiographical novel, “America Is in the Heart,” wandered into a crowded pool hall one day shortly after arriving in Los Angeles.

A few minutes later, two police officers “darted into the place” and shot a young Filipino in the back. “The boy fell on his knees, face up, and expired,” Bulosan wrote.

The cops called an ambulance before dumping the youth’s lifeless body in the street, then “left hurriedly, untouched by their act, as though killing were a part of their day’s work.”

Allos was horrified and bewildered. He couldn’t believe what he witnessed. His fellow pinoys – young Filipino men recently arrived in America – stopped to consider the bloodshed for a brief moment before turning back to their games.

This series explores the unseen, unheard, lost and forgotten stories of America’s people of color.

“They often shoot pinoys like that,” one said. “Without provocation. Sometimes when they have been drinking and they want to have fun, they come to our district and kick or beat the first Filipino they meet.”

When Allos asked why the Filipinos didn’t complain, he replied, “Complain? Are you kidding? Why, when we complain it always turns out that we attacked them! And they become more vicious, I’m telling you!”

Bulosan was a novelist, poet, labor activist and one of the manong, the young men in the first wave of Filipino migrants arriving from 1903 to 1934. His best-known essay, “Freedom from Want,” was published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1943 as a companion piece to Norman Rockwell's famous painting of the same name. It called on a nation at war to honor the values for which its young men were dying.

“America Is in the Heart” is Bulosan’s definitive work, a call to his fellow Americans, a cry for the rights of immigrants and workers by a Filipino who found his adopted country did not live up to the ideals American teachers had imparted onto a generation of colonial wards. The book documents how the earliest Filipino farmworkers were subjected to exploitation, systemic racism, brutal treatment by white law enforcement and anti-miscegenation laws that prevented them from starting families.

Bulosan’s work has been largely obscured by time and marginalized because of his association with liberals and communists in the labor movement. But his writing was important not just during his short life; it remains so as our nation grapples with the same questions and conflicts he wrote about: questions about race and workers’ rights, questions about whose histories deserve to be taught, questions about what it means to be an American.

“Bulosan is emblematic of the Filipino condition,” said Robyn Rodriguez, founder of the Bulosan Center for Filipino Studies at the University of California-Davis. “He was chronicling the early migration and settlement of Filipinos in a hostile society. One of the things that’s so striking about 'America Is in the Heart’ is this dissonance between his main characters, his protagonist and their undergoing this colonial education – America is this ideal, but all those dreams are shattered upon arriving here.

“He saw it as his obligation to use his writing as a way of critiquing the structures of power,” Rodriguez said. “He knew there was power in the pen, and he deployed that power in all the ways he could.”

Jose Antonio Vargas, a Filipino American journalist, author and activist for undocumented immigrants, said Bulosan “speaks to the working-class experience in America.”

“That’s why documenting the manong experience is so incredibly important. We have to remind ourselves. … I have nieces and nephews for whom America is a given; and for Bulosan, it was an open question. His vision of America is very wide-eyed and open – it’s not this blind patriotism.

“He interrogated it. That’s the mindset we need to see more. … Bulosan saw America in all its beauty and all its faults.”

Is this the real America?

Bulosan was born around 1911 in Pangasinan, a province in the Philippines. He migrated to the USA in 1930.

In “America Is in the Heart,” Bulosan described a hardscrabble life with his father, a subsistence farmer, and his mother, who sold salted fish in a village market. His father was forced to sell off his land piece by piece, so without property to inherit and few prospects for employment, Bulosan joined an exodus of young, single Filipino men who boarded steamships for the USA and the territory of Hawaii.

After hundreds of years of Spanish annexation, the Philippines became an American colony in 1898, the spoils of victory after the Spanish-American War. Filipinos who fought against Spain alongside the United States saw the Americans’ demand for independence from England in 1776 as a template for the island nation’s self-rule.

Instead, another war – called an “insurrection” by the United States, as Filipinos fought to keep their own land – “would disrupt life across the provinces in ways that would reverberate over the generations and play a central role in the movement of Filipinas/os to the United States,” wrote Dawn Bohulano Mabalon in her 2013 book, “Little Manila Is in the Heart,” an answer to Bulosan’s book.

The United States sent all-Black regiments overseas, pitting Black soldiers against brown people. A policy of “benevolent assimilation” was adopted even as the Americans brutally fought Filipino guerrillas, calling them by racial slurs “n------” and “goo-goos.” Filipinos’ education by American teachers sent abroad – modeled on the boarding school education of Native Americans at the time that separated them from their families, cultures and languages – snuffed the sparks of Filipino nationalism, culture, languages and traditions.

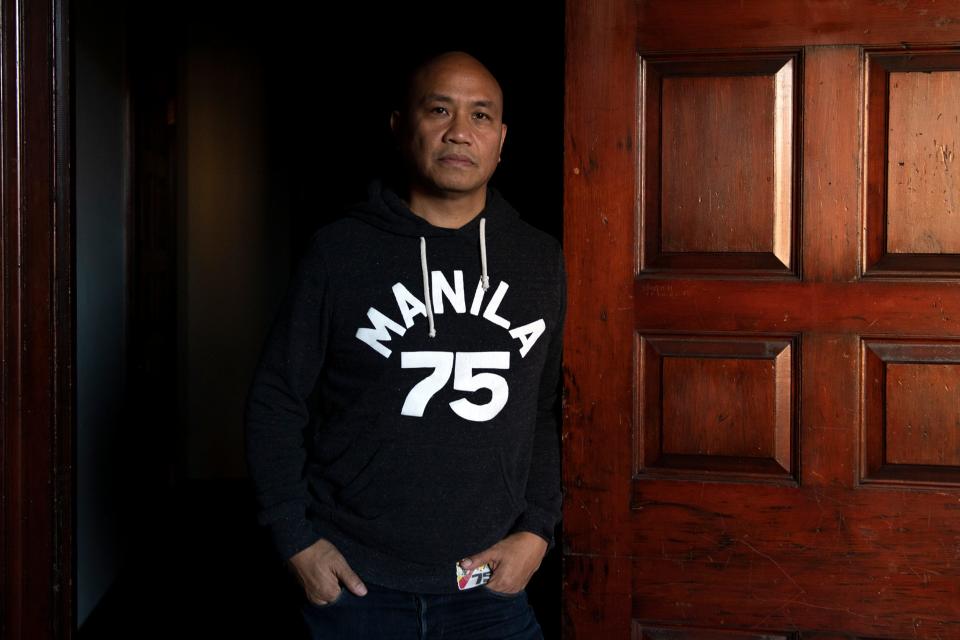

Bob Sampayan’s father was Bulosan’s first cousin. They grew up together in the Philippines and came to the USA in 1930 with high hopes to work, to be educated and to eventually return to their homeland, though Bulosan would never see the islands again.

“They wandered the streets and found what they thought was this beautiful park, and they slept there” upon their arrival, said Sampayan, who had a long career in law enforcement and became mayor of Vallejo, California. “When they woke up at dawn, they realized it was a cemetery. Then, they did what you’d do when you arrive in a new country: They went looking for work, for a place to stay. They worked at various jobs, anything they could do: working in restaurants, busing tables, washing dishes. They worked in agriculture, working the fields, traveling all over the Central Valley.”

Bulosan landed in Seattle, one of thousands of young, single Filipino men who traveled from the fish canneries of Alaska down to Washington, Oregon and California, following crop cycles. Very few Filipino women were allowed to migrate, as men were thought to be a stronger source of labor, and white lawmakers had no desire to see Filipinos bear children who would be U.S. citizens.

The workers were exploited at every turn: Predatory farm managers fired them on a whim, charged exorbitant rents for overcrowded, vermin-infested field houses and worked them to exhaustion. Filipinos were beaten, brutalized, even lynched for talking to white women or going into towns where they were unwelcome.

“I could not compromise my picture of America with the filthy bunkhouses in which we lived and the falling wooden houses in which the natives lived,” Bulosan wrote in his essay “My Education,” an undated work included in “On Becoming Filipino,” a collection of his poems, essays and short stories.

“I began to ask if this was the real America – and if it was, why did I come? I was sad and confused. But I believed in the other men before me who had come and stayed to discover America. I knew they came because there was something in America which needed them and which they needed. Yet I slowly began to doubt the promise that was America,” Bulosan wrote.

Black, brown, exploited

“It’s important for Americans to understand the exploitation that happened in the building of this country,” said Patrick Rosal, a Filipino American poet, writer and professor at Rutgers University-Camden in New Jersey. “The emancipation of slaves and the rise of industrial farming occurred around the same time. They needed workers, but they needed them cheap, so they brought in immigrants.”

Black people freed after the Civil War sought better lives and higher wages, leaving the fields of the South to work in factories in the North; those who’d enslaved them resented paying those they considered less than fully human for labor that had once been free. Rapidly expanding farms in Hawaii, California, Washington and Oregon needed cheap, easily exploitable labor.

“It was a direct result of white supremacy,” Rosal said, “globalizing it through the annexation of the Philippines and using Black soldiers to do it. They needed labor, but they also wondered, just who were these Filipinos? Are they immigrants or citizens? They aren’t Black. But they aren’t white, either.”

In “America Is in the Heart,” Bulosan’s Allos described his first months in America as frightening, violent and humiliating.

Allos saw a fellow worker’s severed arm float past him at an Alaska fish cannery. He ran from a gun-wielding mob of white men after picking apples on a Washington farm; and found himself targeted by law enforcement for the color of his skin, the slant of his eyes and the accent in his speech.

“It was the worst life,” said Dillon Delvo, executive director of Little Manila Rising, a Stockton, California-based nonprofit that advocates for environmental justice and historic preservation.

Delvo’s father came to the USA in 1928, he said, “an 18-year-old man who left everything behind and came with this idea of creating the first Filipino American family.”

That dream would be long deferred; His father was 67 by the time Delvo was born.

“There are a lot of us who had really, really old dads,” said Delvo, 48, “and ... it wasn’t until much later that I found out there were laws preventing them from marrying.”

Filipino men initially were not seen as a threat, but as the Depression threw millions out of work, simmering resentments began to boil over, said James Zarsadiaz, director of the Yuchengco Philippine Studies Program at the University of San Francisco.

“In the 1920s and ’30s, you began to see more Filipinos getting involved with white women and vice versa,” he said. “And it’s not just about them having mixed-race children and interracial marriages, but also white working-class resentment about Filipinos taking their jobs, so there was an economic impetus.”

The manong “were not alone, though they were actively segregated from white society,” said Rodriguez, who is trying to preserve their history, traveling through the Central Valley to talk with farmworkers. “They lived very rich lives with each other.”

Writing for their lives

In the 1930s, Bulosan and other Filipinos, angered by the treatment of their fellow pinoys, as well as the Mexican, Native American and Black farmworkers they encountered, tried to organize them to fight for better conditions. The effort moved in fits and starts, and Bulosan fell ill with tuberculosis.

By 1937, Bulosan wound up in Los Angeles County Hospital, where he remained for two years. He spent the time there reading works by American, European and Filipino writers. Two white sisters, Sanora and Dorothy Babb, supplied him with books by Pablo Neruda, Karl Marx, Walt Whitman, George Bernard Shaw, Mahatma Gandhi, John Steinbeck and José Rizal, a Philippine nationalist who was executed by the Spanish for sedition in 1896.

Bulosan endured surgeries on a cancerous leg, to remove lesions from his lungs and to remove a kidney, leaving him frail and vulnerable for the rest of his life.

“One day, before I came to the hospital, I was talking to a Negro boy about race and prejudice and he asked, ‘But there isn’t any prejudice against the Filipino in this country, is there?’” Bulosan wrote to a friend in 1937. “When I told him some of my experiences he was surprised, believing that Negroes were the only persecuted race in America.

“We who know prejudice sometimes have a tendency to believe that we are the only ones discriminated against,” he continued. “There have been times when I have been sad and bitter and felt this way. Then I remember that there are thousands of people besides Filipinos who have had similar experiences – Negroes, Chinese, Japanese and even native-born whites. And I began to feel less alone, remembering those people and those few Americans I have known without a trace of prejudice.”

The Filipino Agricultural Laborers Association staged a strike in 1939, and after World War II, Bulosan helped organize cannery workers’ and asparagus pickers’ strikes along with Rudy Delvo, Claro Candelario, Chris Mensalvas and Larry Itliong, who would go on to lead the Delano grape strike/boycott of 1965-70 in California along with Philip Vera Cruz (a fellow Filipino), Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta.

“I met (Chavez), and one of the things he talked about was Carlos Bulosan and what Carlos tried to do in the 1930s and ’40s,” Sampayan recalled. “He was trying to get people to unionize but also to be part of mainstream America while also retaining their roots and culture and heritage.”

“Studying Bulosan is studying the history of work itself,” Rosal said. “There’s a difference between studying the tables and the statistics, and the stories: the exploitation, the way they lived, the danger that was a part of their everyday lives. ... Bulosan gives us things economics don’t: the stories of the workers and their interior lives.”

Even as Bulosan’s writing gained attention – besides The Saturday Evening Post, his work appeared in The New Republic and The New Yorker – he remained poor, sharing money with destitute friends, spending it, funneling it into the labor movement.

As the Cold War began, federal law enforcement targeted liberals who’d been active in the labor movement.

According to the University of Washington’s online archive of his work, Bulosan was under government surveillance as he worked with a cannery workers’ union. Five of its officers were targeted for deportation, and Bulosan was among those who fought successfully for them to remain – selling signed and numbered copies of his poems to benefit the defense fund.

Hospitalized again in 1952 for tuberculosis, Bulosan struggled with alcoholism and homelessness after he was released from the sanitarium a year later.

Bulosan died Sept. 11, 1956, “when, after a night of drinking with a labor lawyer who was a close friend, he wandered around the streets of Seattle,” Filipino poet and essayist E. San Juan wrote in the introduction to “On Becoming Filipino.” “At dawn he was found sprawled on the steps of the City Hall, ‘comatose and in an advanced stage of broncho-pneumonia.’

“He was less a victim of neurosis or despair than of cumulative suffering from years of privation and persecution,” San Juan concluded.

Bulosan “was victimized by McCarthyism at the height of the Cold War, when those who stood on the side of the labor movement were seen as threatening,” said Rodriguez, founder of the center that bears his name. “And that helped to make him disappear from the national narrative.”

Still, he and the other manongs persevered, she said. “There were some successes; they managed. And that’s important when you see what it really was to be a minority then, and what can happen when minoritized people come together.”

Preserving Filipino stories

Many stories of the manong have been lost or overlooked for a variety of reasons: U.S. history curricula have long failed to tell the stories of marginalized people, people of color and non-European immigrants. The manongs’ bachelorhood meant many of them had no sons or daughters with whom to share their stories. Some who married wed white women and assimilated into American society, raising their children less as Filipinos and more as Americans.

“It’s very much a part of Filipinos to embrace full-on American assimilation,” said Zarsadiaz of the University of San Francisco. “They might want their children to be Catholic or to eat Filipino foods, but they teach them that they’re Americans first.”

That mindset is rooted in the colonial relationship the Philippines had with the United States and its influence on Filipino culture.

“To them, (English) is the language of modernity, and they embraced it,” Zarsadiaz said.

Zarsadiaz said some manong may not have shared their stories because they didn’t want to relive painful memories of the racism and brutality they faced.

“Some of that might be trauma, and some of it might be that way of, just do the damn thing and don’t talk about it,” he said. “It’s a very Filipino thing to just tough it out. There’s this stereotype of Filipino resilience; it took a long time for them to work their way to a decent life – not a rich life, but a decent life.”

The Bulosan Center faces an existential crisis, Rodriguez said: State funding is set to run out by the end of the 2021-22 academic year, and there is little support from the University of California-Davis.

Rodriguez plans to leave academia after 30 years and start a nonprofit to preserve the stories of the manong and the field workers, labor organizers and other Filipinos who came after them. She plans to work directly with community groups, free from the constraints of academia, frustrated and tired at having to fight the university for resources to support the Bulosan Center.

The nonprofit would be named for her son, Amado Khaya, an activist and community organizer who went to the Philippines to live and work with indigenous farmers on the island of Mindoro as they fought to preserve their land and way of life. He died in August 2020 from severe food poisoning.

Rodriguez has been traveling on her own through the Central Valley, collecting stories for the Central Valley Empowerment Alliance, which launched the Larry Itliong Resource Center in late October.

Preserving Filipino stories has been an uphill struggle, she said.

There’s an urgency to the work: “Many of them are getting older, and there’s not a lot of physical evidence, no employment records or photographs. All we have is memories, and some of them are fading, and then what?”

“We have to tell the stories that were not told, but we also have to connect them to our present to sow the seeds of community among us – that’s why it matters to a wider audience,” said Rosal, whose latest collection of poetry, “The Last Thing,” examines life in the USA and the Philippines.

“These are American stories not being told – and that’s a detriment to America itself,” Delvo said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Filipino author Carlos Bulosan's complicated love for America