Composting can help reduce Columbus’ highest source of greenhouse gas emissions

Waste experts say composting and reducing food waste are where individuals and planning experts need to direct their energy over recycling efforts to have a more profound impact on the environment and mitigate climate change.

At its core, the recycling system is broken, they say. And while it diverts some waste out of landfills, managing our food waste through composting is a much more powerful use of the public’s time and energy, especially for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

“The organic waste that ends up in a landfill is the biggest contributor to climate change from the waste management system,” said Sintana Vergara associate professor of environmental resources engineering at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt.

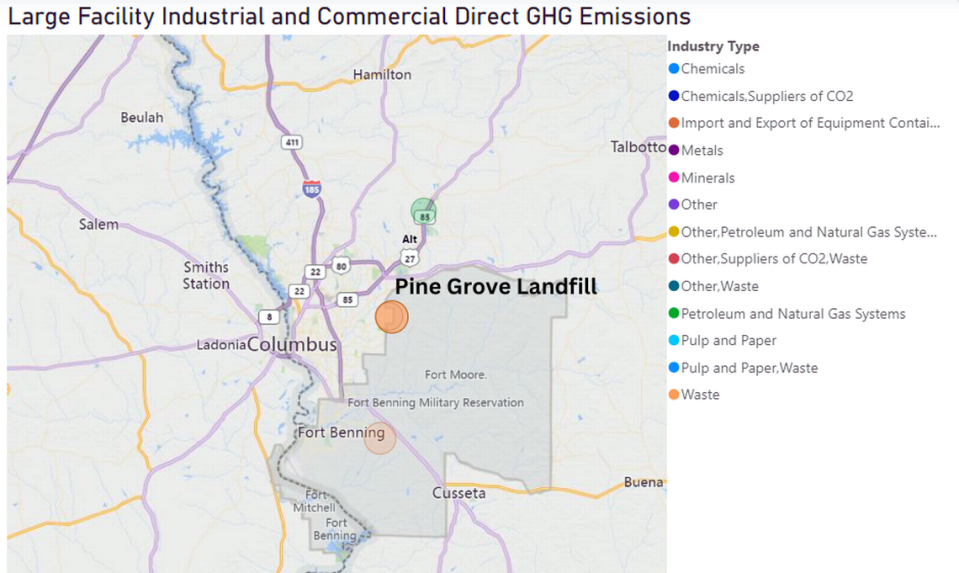

In 2021, there were 99,185 metric tons of CO2 equivalent emitted from the Columbus Pine Grove landfill, according to Drawdown Georgia (the climate solutions nonprofit based in Atlanta). This is the largest facility CO2 emitter in Muscogee County.

“When you send food waste to a landfill, you have pretty much the largest climate impact you can have because you have biodegradable waste, and 50% of it is going to end up in the atmosphere,” Vergara said. “If you send food to a landfill the conditions are anaerobic, meaning there is no oxygen, so when it breaks down the carbon is emitted as methane which is a very powerful greenhouse gas.”

Methane is 27x more potent than carbon dioxide or has a 27 global warming potential (GWP) equivalent.

Bill Drummond, professor of city and regional planning at Georgia Tech, noted that the Drawdown Georgia tracker doesn’t pull out methane separately when creating these calculations. These numbers come directly out of the EPA state-level greenhouse gas inventory.

Composting would remove food waste from the landfill, having a direct impact on potent greenhouse gases from Columbus’ largest emitter. “Methane from landfills is significant,” Drummond said.

“From a climate perspective, you get more bang for your buck from composting [than recycling],” Vergara said. Additionally, “you get the most climate benefit from investing in compost than you do for recycling.”

Columbus’ Recycling Waning

Columbus’ recycling participation rate is at 35%, with 57,000 residential homes utilizing the service that is included in the $18 waste fees per month they are already paying. The latest numbers for Pine Grove Landfill are 76,000 tons of waste every year.

The reason that experts say recycling system is broken throughout the U.S. rests with three problems: most plastics can not withstand being remade into something else, there is a high level of contamination that results in plastic and other recyclables going into landfills, and there remains a lack of interest in buying back something that has been used, especially plastics.

Despite only one-third of Columbus residential houses participating in recycling, The Columbus Recycling Center still manages 10,584 tons of aluminum, cardboard, paper, and plastics annually. Their operation is to sort materials into separate piles and toss contaminated materials to the landfill pile. The material that makes it through is sold to Pratt Industries in Conyers, Georgia.

Pratt Industries says 32% of the recyclables sold to them were deemed trash.

“That’s not uncommon, not high but not low,” President of Pratt Industries, Shawn State said in an email.

Because of the different types of elements that make up plastic, much of it isn’t recyclable. This is a ubiquitous problem throughout the world, not just in Columbus.

“Plastics are polymers,” Vidana said. “They’re basically a mishmash of chemical compounds. And for that reason, it’s very difficult to recycle them.”

Pratt Industries accepts all types of #1-7 plastics, as well as aluminum and steel cans. However, State said, “There is not a consistent market to sell #3-7 to, and may go to landfill once other material is sorted out.”

City of Columbus Integrated Waste Manager John Pittman wants recycling participation to double throughout Columbus. He believes education is the way to reach that goal.

“It is a very low number [35%], we have some work to do,” Pittman said. “People don’t know and understand what they can and can’t recycle. We need to create more programs within the city itself to encourage more participation.”

Right now the Recycling Center receives $1.2 million dollars annually to operate and brings in $428,000 dollars in revenue.

Composting is on the mind of Mr. Pittman. He pointed to Athens-Clark County as a “top-of-the-line composting program” in Georgia. “That’s the model,” he said.

Athens-Clark County launched its composting program back in January 2011. Due to the size of the county and the mounting pressures of the landfill reaching capacity thresholds, there was a good driver to embrace as many diversion tactics as possible.

Joe Dunlop, The Waste Reduction Administrator of the Athens-Clark County Solid Waste Department said the program averages 244 tons of food scraps per month.

From a reduction perspective, food waste and cardboard are Dunlop’s concerns, not plastic.

“If you are looking for things to divert, plastic gets a lot of attention, but there is a heck of a lot of cardboard and food waste,” he said.

According to Drawdown Georgia, Food waste makes up 24% of municipal solid waste in the U.S.

Cities can make a difference

Athens-Clark County’s situation is an anomaly in terms of reaching capacity. Muscogee County has already filled and closed four landfills. Pine Grove is the latest and fifth landfill. Pine Grove is estimated to have 30 years left with current rates of waste.

Michael Elliot, Planning professor and director of the master of city and regional planning program at Georgia Tech, blames a lack of incentives and a lack of city action when it comes to managing food waste.

“Cities are central to decision-making around waste and waste management,” Elliot said. ”Really this is about getting local jurisdictions to pay more careful attention in terms of residential waste. There are no incentives for anyone to manage [food waste] more productively. [Consumers and restaurants] just want to get rid of it. They aren’t in the business of dealing with waste.”

Pittman said there is not enough funding to move forward with a composting program in Columbus right now.

The Public Works Department applied for the Georgia EPD Solid Waste Trust Fund grant that would secure $ 1 million dollars to start the program. Pittman recently found out that they were one of several applicants throughout the state, and Columbus’ waste department “didn’t make the cut this time.” The Department plans to apply again to secure the funding.

Vergara suggests that it is not an expensive endeavor and the efforts for composting and recycling are both important. “A facility is not very expensive,” she said. “It’s the land and space that is expensive.”