Confederate general’s museum adopts new history — and possibly his Black inventor grandson

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sandra Morgan grew up in Cleveland as one of the granddaughters of Garrett Morgan, a famous and beloved son of the Black community there, a famous inventor, civil rights activist and businessman. He patented the early stoplight and the first gas mask, and went on to create a successful line of hair products.

He moved to Cleveland as a young man after a childhood of poverty in Claysville, outside of Paris, determined to get away from the racism that permeated Kentucky, a divided state that still cleaved to Southern values. As Sandra Morgan said: “There were very few opportunities for him in Kentucky, and he was determined he was going to work with his head, not with his hands.”

On Sept. 24, Sandra Morgan will speak about her grandfather’s life as a Kentuckian and an Ohioan at the Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation with a speech titled: “Patented: The Innovative Spirit of Garrett A. Morgan.” But she will inevitably be asked about a more elusive question: Was Garrett Morgan the grandson of famed Confederate General John Hunt “Thunderbolt” Morgan, guerrilla fighter, whose equestrian statue once stood in front of the Fayette County Courthouse?

That this question can even arise at the Blue Grass Trust, once the bastion of white establishment Lexington history, is in itself interesting, and shows how quickly historical narratives can morph amidst huge societal change. The Trust’s house museum at the corner of Second and Mill has recently gone from being called the Hunt Morgan House to its original name, Hopemont; inside, the shrine once devoted to “Thunderbolt” and his Rebel Raiders is instead centered on Hunt Morgan’s grandfather, John Wesley Hunt, Lexington’s first millionaire, and the enslaved people who made him rich on hemp farming.

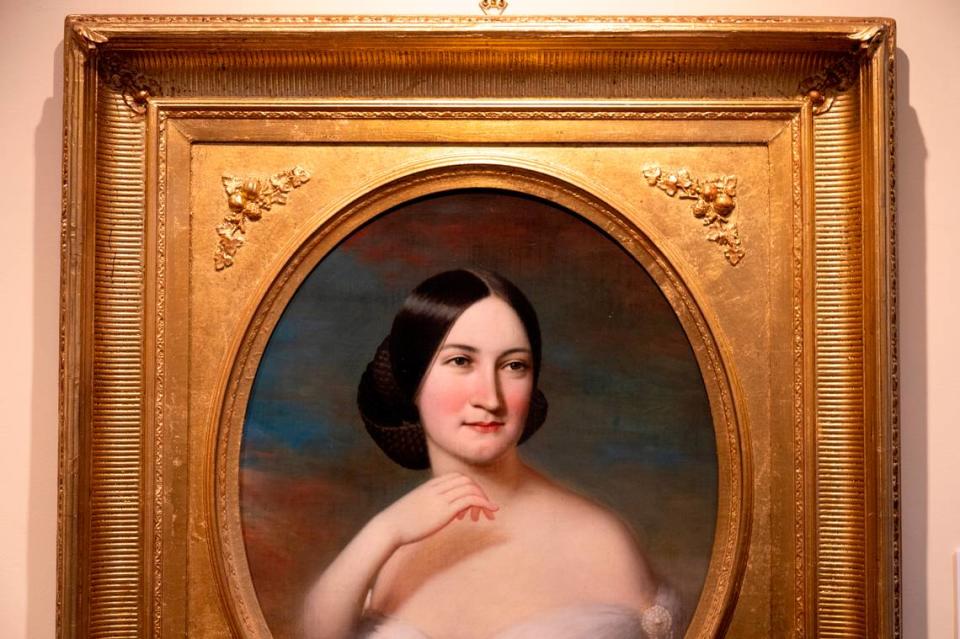

They have even hung a large portrait of Garrett Morgan in one of the downstairs rooms, across from one of Thomas Hunt Morgan, John Hunt Morgan’s nephew who was the first Kentuckian to win the Nobel Prize (for his research in genetics, no less). Even if the bloodline is not direct from the Confederate to the civil rights activist, the Blue Grass Trust has claimed him as a descendant whose portrait belongs in the 1814 mansion built by the enslaved.

It’s a dramatic turnaround at numerous historical sites and preservation societies that long focused on the narratives of their rich, white forebears. It’s happening at places like the Ashland Estate, where tours now admit that Henry Clay’s distinguished political career was fueled by the enslaved people who built his wealth. They are also starting a painful conversation, the acknowledgment of a brutal past of rape and coercion by white slave owners upon enslaved women.

It’s also more difficult to tell a history of people who were often forbidden to learn to read or write, a history that depends largely on stories passed down through the generations. Yvonne Giles, the historian who has uncovered much of what we know about Black history in Lexington, says that despite a couple of books that state Sydney Morgan, Garrett’s father, was John Hunt Morgan’s son, she has been unable to find a direct connection between them. She says she will wait to see what is uncovered. “You cannot change history,” she said. “You embrace it and you tell the broader picture.”

‘We are all related’

Sandra Morgan, an administrator at Kent State University, says her family had always heard the rumors about possible white ancestry, but they had no proof. Also, it was external to the story of Garrett, who was a major figure in Cleveland, first and foremost “a problem-solver,” someone who started working at a textile factory, and then quickly figured out a way to fix sewing machines that frequently broke. He also developed what he called a “smoke hood” in 1914, then in 1916 used it to rescue workers trapped in a water intake tunnel under Lake Erie.

Then last year, Sandra Morgan was contacted by John Jay Buchtel, who found her through the Case Western University historical archives, where some of Garrett Morgan’s archives are stored. Buchtel was a descendant of Mattie Ready Morgan, John Hunt Morgan’s second wife with whom he had one daughter who died in her 20s. Mattie Ready married again and had more children to whom she recounted the stories about her first husband and his Confederate derring-do. Buchtel, who lives in New York City, had seen a few books and the Wikipedia entry that cites a Sydney Morgan as John Hunt Morgan’s son, although he said there were no stories in his family about a possible relationship.

“Maybe Mattie Ready didn’t know or maybe she knew and didn’t tell,” Buchtel said in a phone interview. “If that is part of the story it may be about the extent to which the Southern ladies knew and understood the Southern men were having relations with the enslaved, and how they internalized it. All that history of the South is touched by that story.”

However, Buchtel himself has no doubt about the connection, and is anxious for proof. Probably the most famous such relationship in history is that between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, which came out of a strong oral history tradition long denied by Jefferson’s white descendants until it was proved by DNA that Jefferson had fathered at least six of her children.

Buchtel had also heard a story from the Trust about a Black man who came on a tour of the Hunt Morgan House a decade ago, and told the docent he was a descendant of the Morgans. The docent dismissed it as impossible, telling the man that Morgan had no male progeny. The docent did not take down the man’s name.

‘If John Hunt Morgan had a child with one of his slaves, and that child went on to produce progeny that touched the history of America, it reaches into the heart of our darkness and puts human light on it because it shows the extent to which we are all related and important to each other,” Buchtel said.

Sandra Morgan is more pragmatic. “It is what it is,” she said. “I’m clear eyed about race relations throughout our history and I would say you see people who are fair or medium complected you know there was some intermingling somewhere. Never mind John Hunt Morgan, you name it, it’s in our family. We’re a rainbow coalition.”

She also wants it to be clear that she did not search out the Morgan relationship or even get that interested in it until contacted by Buchtel.

“I didn’t go looking for the Hunt Morgan family, they came looking for us,” she said. “I’m grateful for that because it’s an acknowledgment that many others have not received.”

A lost Lost Cause

Like many Lost Cause efforts, it’s not exactly clear when “Hopemont,” the stately Federal mansion built by John Wesley Hunt became “The Hunt Morgan House,” a house museum dedicated to the Civil War exploits of one Confederate general who decided to go to war in defense of slavery.

The place the house sits, Gratz Park, is a fascinating example of Lexington’s own historical schizophrenia; Hopemont overlooked a Union encampment in the park, and Frances Peter’s “A Union Woman in Civil War Kentucky,” detailed exactly which houses on the Park housed sympathizers to which side. But post-Civil War, Kentucky generally and Lexington specifically became retroactive Confederate entities, particularly into the Jim Crow years, when the United Daughters of the Confederacy paid $7,500 for the statue of John Hunt Morgan to be placed in front of the courthouse. The General Assembly kicked in another $7,500 in taxpayer funds, according to “Creating a Confederate Kentucky” by Anne Marshall. In 2017, under community pressure, the city moved the statute to the Confederate section of the Lexington Cemetery.

“Ten years ago, the house was doing homage to John Hunt Morgan, and now we’re trying to give a more balanced view of the Civil War,” said John Hackworth, a Trust board member who has been deeply involved in the historic makeover.

To that end, the tour focuses more deeply on John Wesley Hunt and the enslaved people who produced the hemp crop in early Lexington that made Hunt a wealthy man with 12 children. Upstairs, there is Civil War room that displays both Confederate and Union paintings and mementos. In the basement, visitors are able to see where enslaved people cooked meals and possibly lived.

Until this year, the house used to be the meeting place of the Morgan’s Men Association, formed in 1868 after John Hunt Morgan’s former soldiers met at Morgan’s re-interment ceremony at the Lexington Ceremony. “The men pledged fidelity and affection for each other for as long as they lived and resolved that the memory of our illustrious and beloved leader shall ever be as indelibly stamped upon the tablets of our hearts as his name is written on the undying page of history,” according to the website.

However, last month the Trust told the group to find another meeting place.

“We told them they were no longer welcome,” said Hackworth. “We just feel they’re honoring something that we don’t want to honor — the whole Confederate cause. The Blue Grass Trust made a decision in severing that relationship that we would get a lot of blowback — we’re willing to take it because we think it’s the right thing to do.

Sam Flora, the group’s secretary and contact, did not return several calls for comment.

“The pace of change is so fast that it upsets a lot of people,” Hackworth said.

‘Can’t change history’

Although “upset” would be too strong a term, Yvonne Giles is a little concerned at the pace at which the Trust is overturning previous narratives. It’s one thing, she said, to expand the story of Hopemont and the Morgans, but it’s another if they are now trying to downplay the role of the Confederacy.

“They can’t change history, and that’s what they’re trying to do and I’ve told them that,” Giles said of the Trust, which recently named one of its preservation awards after Giles. “The tide now has swung to giving a more balanced history, but they still need to say John Hunt Morgan was a Confederate guerrilla. There’s too much information that you can’t ignore.”

Still, even if Hunt Morgan becomes a Confederate in the attic, the Trust deserves credit for taking him off the pedestal upon which he stood for so long. That new historical approach includes the adoption of Garrett Morgan, documented or not.

“Do we have ironclad proof?” said Hackworth. “No, but we accept it as part of the story. That’s the tradition we’re working from.”

It’s a one-sided adoption, as it were, since Garrett Morgan made it clear that he had to leave Kentucky in order to fulfill his potential, and he and Cleveland embraced one another. Once his mother had moved up to live with him, Sandra Morgan thinks he rarely or ever went back to the commonwealth.

“He is wholeheartedly claimed by the state of Ohio and city of Cleveland,” she said. “This is where he became himself, although Kentucky had considerable bearing on his beliefs and his work ethic and his ideas about himself.”

Sandra Morgan will give a speech titled “Patented: The Innovative Spirit of Garrett A. Morgan” as part of the new Hopemont Lecture series on Sept. 24 at 7 p.m. at the Thomas Hunt Morgan House, 210 North Broadway. Proof of vaccination is required. To register for the Zoom or in-person event, click here.