Confederate piracy and the tale of Bonnet Shores' protection of Narragansett Bay

On the night of June 26, 1863, a Confederate Navy raiding party boldly sailed into the harbor at Portland, Maine, aboard a captured fishing schooner. They hijacked the Caleb Cushing, serving in the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service (predecessors of today’s Coast Guard). The Cushing was the largest Union warship north of Boston.

When the wind died the following day and they could not outrun pursuing steamboats, the raiders scuttled the cutter before being captured.

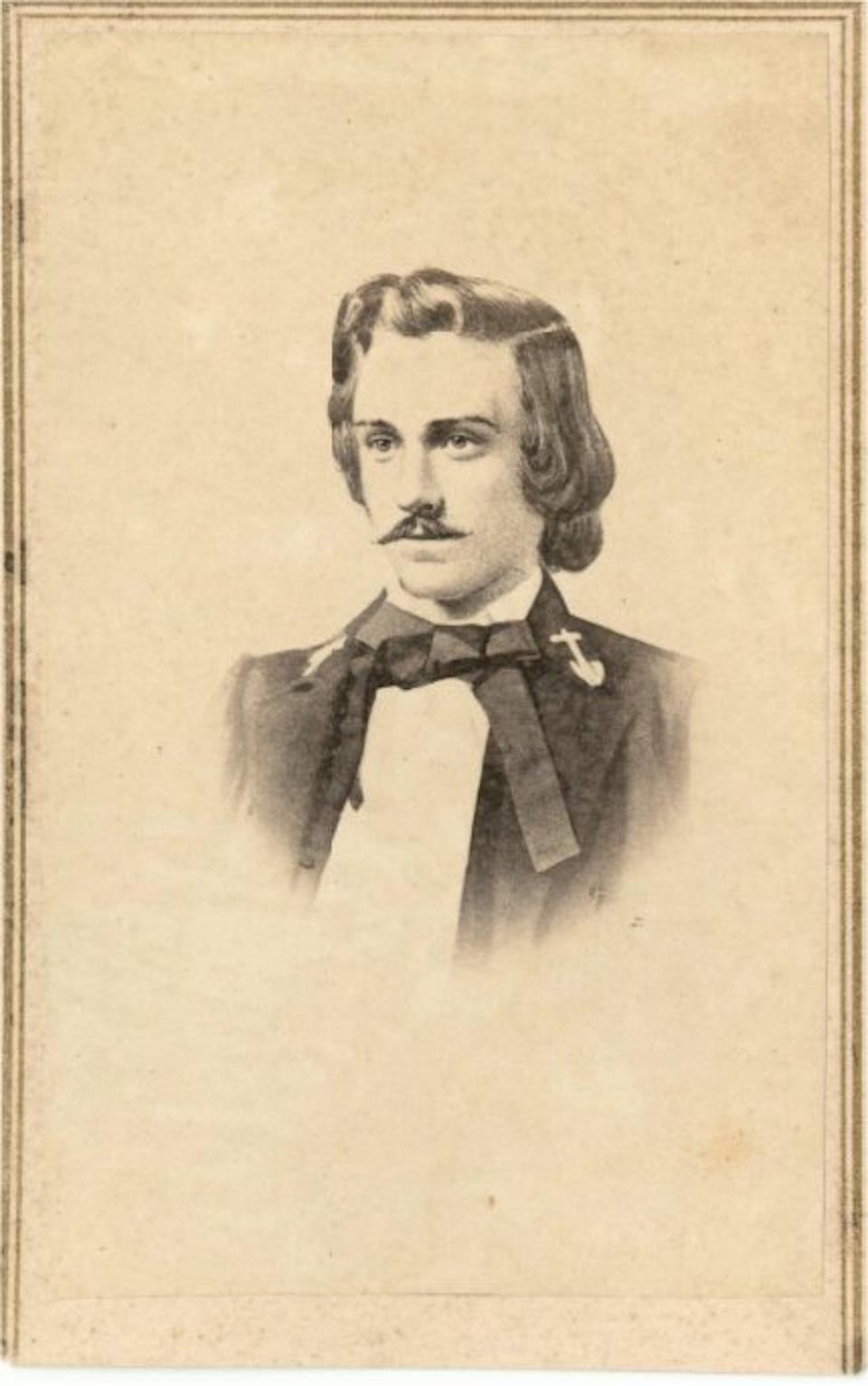

This bit of derring-do was organized by young Charles W. Read, who graduated last in his class from the Naval Academy in 1860. A Mississippi native, he joined the Southern cause, and within two years he became known as the "Seawolf of the Confederacy" for his exploits and daring. Clearly, he did better at sea than in a classroom.

Hijacking the revenue cutter capped a three-week run during which he and his small crew captured 22 prizes from the Chesapeake to Maine. They terrorized Union merchant shipping while spreading fear among Northern communities from Virginia to Maine.

Lieutenant Read’s plan and tactics

While serving aboard the Florida down South, Read proposed a daring scheme to his captain. “Next time we capture a fast merchant vessel, let me go aboard with a small crew and convert it into a raider. The Yankees will never suspect until it’s too late.”

Read’s plan was simple: wreak havoc among Union shipping, then, when his raider became too recognizable, scuttle it and take over a different ship.

The July 11, 1863, issue of Harpers Weekly explained:

“… they captured the bark Clarence on May 6, which was converted into a pirate and Lieutenant Read was put on board. … She burned three vessels, then [on June 12] captured the Tacony to which craft Read transferred his crew and guns and burned the Clarence.”

Tacony caused the most destruction, and according to a 1909 report in U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, “… by the 26th of June there were forty-seven armed vessels scouring the seas in every direction for this bold little rover. Even the practice ships from the Naval Academy, with the midshipmen aboard, were sent out.”

Why residents of Northern cities panicked

Most historians consider June 1863 to be the high-water mark of the Confederacy. Gen. Robert E. Lee’s gray-clad Army of Northern Virginia was invading, marching through Maryland and into Pennsylvania.

With most of their military units already deployed to counter Lee’s advance, the last thing local officials needed to worry about was a threat from the back door.

On June 22, Read upped his game. He seized the Isaac Webb, westbound from Liverpool to New York. This was no run-of-the mill merchantman; it was a transatlantic passenger ship with more than 700 souls on board.

In exchange for a $40,000 ransom bond, Read allowed the ship to continue its journey.

When the Isaac Webb reached New York, the howls for federal protection increased. Insurance rates were skyrocketing, and some captains declined journeys until the threat was neutralized.

The raid on Portland

The Tacony’s final prize was the schooner Archer, taken June 25. Read wrote in his journal:

“The latest news from Yankeedom … they have a description of Tacony and overhaul every vessel that resembles her. During the night we transferred [to] the schooner Archer. At 2 a.m. we set fire to Tacony.

“No Yankee gun boat would ever discover or suspect us; therefore, I think we will dodge our pursuers …”

The following night Read sailed Archer right into the Portland harbor.

Portland was a lucrative target, especially since two steamers were moored there. Read planned to seize one as his next raider and shell the city as he left. With a steamboat he could geometrically increase his seizure of sailing vessels and make it even more difficult for the Union Navy to catch him.

He had to modify his plan once he realized he did not have enough time or engineering manpower to fire up the cold boiler of a steamship.

Plan B was to seize the revenue cutter.

Threat to Rhode Island?

Newport Mayor William H. Cranston telegraphed the Navy on June 25, “… a rebel pirate, supposed to be the Tacony, destroyed several fishing vessels outside our harbor yesterday. Will you not give us an armed steamer? Our harbor is one of the most important of the coast.”

In his diary Read had written, “It is my intention to go along the coast … burning the shipping in some exposed harbor and cutting out a steamer.”

He could have chosen Newport just as easily.

If Confederate pirates could capture a 100-foot schooner under the nose of Union forts in Maine, they could strike anywhere.

President Lincoln gets involved

Hearing about the Portland raid, Rhode Island Gov. James Y. Smith sent a telegram to President Abraham Lincoln, expressing grave anxiety about the unprotected condition of Narragansett Bay.

“There is nothing to prevent a rebel incursion through the West Passage, exposing [Providence] to destruction. … I respectfully request immediate authority to construct, arm and man suitable earth works at the expense of the federal government …”

The White House responded the same day, granting permission and funding. (As an aside, can you imagine the bureaucratic process such a request would have to go through today?)

According to the 1864 book "Rhode Island in the Rebellion," a detachment was to be “stationed at the Bonnet near the South Ferry on the Narragansett shore, covering the approach to the West Passage.”

Smith ordered to duty “a light battery under Col. Edwin Gallup [Providence Marine Corps of Artillery] and a company detailed from the 1st Regiment of R.I. Militia composed of students in Brown University under Capt. John Tetlow.”

Tetlow, still an undergrad, was experienced in the field. He had volunteered for the 10th R.I. Volunteer Infantry, which served for three months in the summer of 1862 defending Washington. Tetlow graduated as the valedictorian of Brown’s Class of 1864.

Bonnet Shores: More than a beach getaway. Exploring its Revolutionary roots

Who were these Brown University cadets?

When war broke out in 1861, a patriotic fervor swept Brown, and the students created a military organization. They quickly recruited 78 college mates, who added military training to their academic workload. They borrowed weapons from nearby Rhode Island militias, and when it was too cold to drill on campus they used the 1st Light Infantry Armory, at the corner of Weybosset and Dorrance streets.

The students elected their own officers, a common practice in early militias. They soon became recognized for their mastery of drill and basic soldiering skills. In the spring of 1863, the cadets were absorbed into the R.I. Militia, becoming known as Company I, First Regiment, Second Brigade.

All of a sudden, they were in the real Army.

Return to Bonnet Point — the stories come together

This reorganization coincided with the reports of “Rebel Pirates” operating a few miles off the Rhode Island coast. A Confederate raider was reportedly nearby, “with her prow turned toward the peaceful waters of the Narragansett.“

Rhode Island's knowledgeable and efficient state archivist, Ken Carlson, dug out an 1863 military file titled “Defenses of Narragansett Bay: June 27 – July 18, 1863.”

These 18 pages of orders and reports offer a fascinating snapshot of this little-known deployment.

The cannons and men (three sections of two guns each) went to South Ferry by tugboats, while the horses took a special train on the Stonington railroad.

Unfortunately, however, this file does not shed much light on the nature of the new battery installation. It is not clear whether Gallup’s men reused the Revolutionary era earthworks or constructed new ones nearby.

They selected a site about 2½ miles south of the ferry “on the so-called Bonnet, which commands the bay, and at which point any vessel can be reached with the guns under my command.”

The ammunition boxes held sufficient ammunition to meet any emergency – solid shot, shell, shrapnel and canister.

On July 15, after the threat had abated, the former cadets were relieved from duty. Their orders included the paragraph: “The commandant of the post takes this opportunity to express to the officers and men of Company I his sincere thanks for their gentlemanlike conduct and soldierly bearing during their stay at this camp,” signed Edwin Gallup, Lieutenant Colonel, commanding.

They returned to Providence and “delivered up their arms and equipment,” thus ending their military adventure at the Bonnet.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Confederate piracy: How Bonnet Shores helped protect Narragansett Bay