When the Confederates raided York, everyone played with fire

In their day, these four Lancaster County men had worked with their heads and hands, making things, big and small, simple and complex.

And this was their biggest job yet, suspended above the Susquehanna River, 600 to 800 feet from the west shore. But John Denney, Jacob Rich, John Lockard, and Jacob Miller, among others, weren’t making anything this time.

Some had experience in blowing things up, and they were planting explosives to sever a bridge – and a mile-plus-long span at that.

It was late June 1863 — 160 years ago — and it was hot and they were playing with fire. Indeed, fire – or threats of flames – would form a big part of this story.

They worked with urgency on the fourth span from the Wrightsville side, cutting through the covered bridge’s roof, down to the sides then stopping at the support arches.

They bored holes in the arches and charged them with powder, attaching fuses.

Surely, when they lit those fuses, the explosions would drop the deck to the water 15 feet below, making it impossible for enemy raiders fronting them to cross and gain a stronghold in Columbia on the east bank.

The men waited for orders, Miller, a Black man, sitting cooly on the edge of a pier. He would not need a match. The cigar he was smoking would do that job.

York’s Civil War surrender at 160: ‘It was not York’s finest moment’

Civilians light fuses

That Miller, a freedman, could be so relaxed was remarkable. He would soon be looking down the barrels of Gen. John B. Gordon’s 1,800 men, bent on taking that span and then possibly marching to pressure Harrisburg from the rear. Or maybe even on to Philadelphia. The going had been that easy so far.

If Miller escaped the Minie balls and cannon shot, he could fall into the hands of these Southerners, known to send Black people South, freed or enslaved.

As he sat, those dust-covered Confederates were at the end of a 22-mile waltz, gaining York without contest earlier that day and then entering the river region and its coveted bridge. York’s town leaders had approached Gordon in his camp that day — actually twice — surrendering the town, fueled by the concern that his men would burn it.

Facing the bridge and the Union’s horseshoe-shaped defensive line at Wrightsville, the Confederates pushed a mashup of 1,500 Union defenders through the bridge. The retreat was orderly, but the bridge was then undefended.

The order came to blow up the span, and time for Miller to apply his cigar to the fuses.

Lee’s big plans

Those Confederates rushing the bridge were the eastern-most probe of the Confederate summer incursion on Northern soil.

Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army was there at the end of a long march to live off Pennsylvania’s bounty. At the same time, nature could replenish the Shenandoah Valley’s breadbasket without the demands of 60,000 hungry gray-clad men and possibly even more combative Union soldiers.

Lee wanted to draw Union defenders away from defensive positions around Washington, D.C., and engage them in a pitched battle. That mission would be accomplished in the Battle of Gettysburg just days away.

And if all went well, he could pressure — or even take — the Northern capital of Harrisburg. President Abraham Lincoln’s war wasn’t going well in the first place, and putting a capital city north of the Mason-Dixon Line at risk could cause support for the war to dissolve.

So here on that Sunday, June 28, one of Lee’s three corps commanders, Gen. Richard Ewell, was with one of his three divisions fronting Harrisburg.

A second division commander, Gen. Jubal A. Early, Gordon’s boss, spread his 6,600 infantrymen, cavalry and artillery men through the middle part of York County.

His most trusted brigade, under Gordon, was marching under orders to take the bridge.

If they could grab that span and march north to Harrisburg’s rear, they could squeeze the capital — Ewell in front, Early in back.

More: Gettysburg 160th anniversary offers chance to learn about York County Civil War story

Fire a foe to bridge

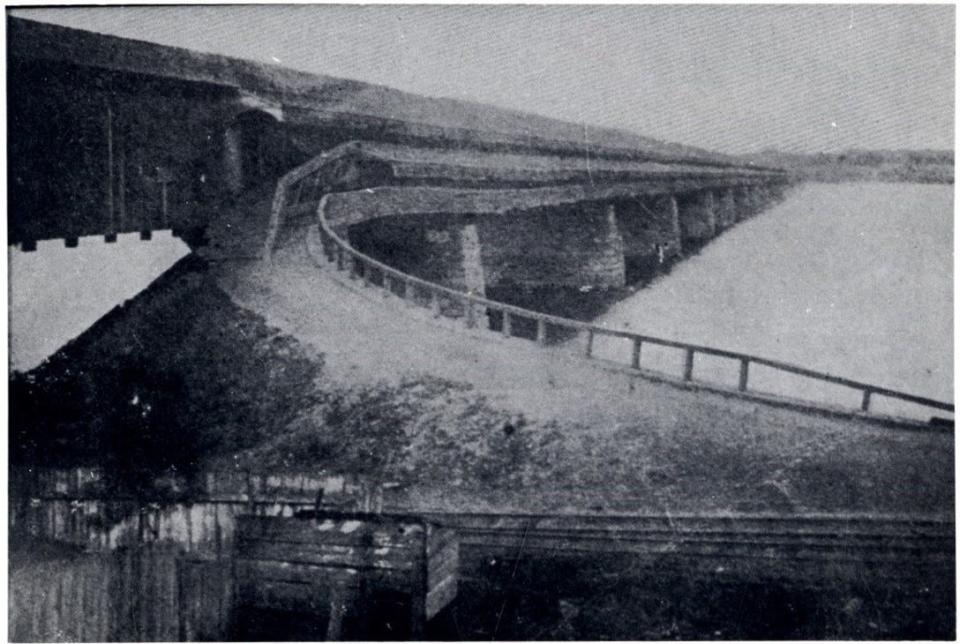

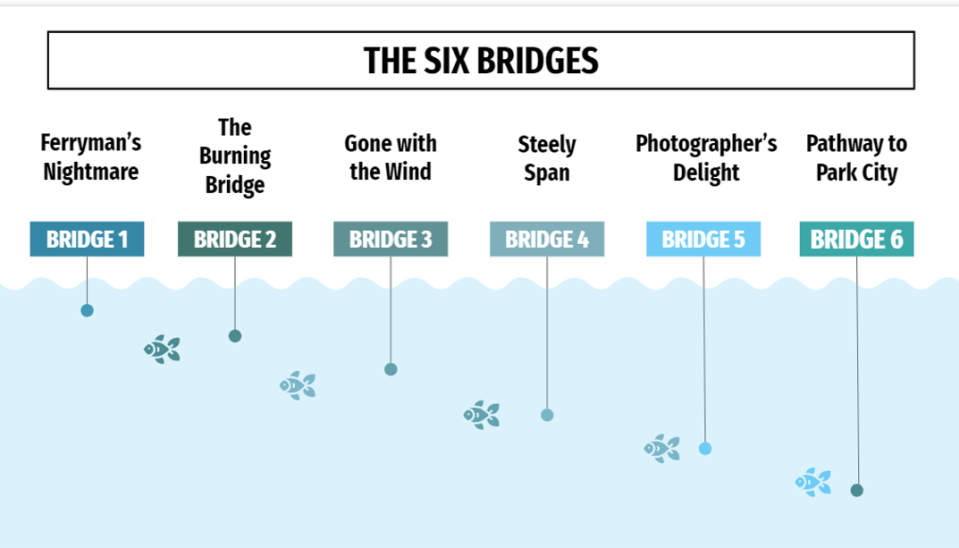

The targeted Susquehanna River bridge was not just long at 5,620 feet.

It was 40 feet wide and built to withstand the ice that pushed away its predecessor in 1832.

Ice aside, fire would be a problem with those heavy beams and arches. Mules pulled locomotives across to prevent sparks from the stacks setting the roof’s supports ablaze. The roof was not there for looks, but a lid to keep the elements from rotting the rail ties and bridge deck.

This bridge was also rare in the Lower Susquehanna. Ewell’s men peered at a humped-back covered span connecting the Susquehanna’s west shore with Harrisburg. And a third bridge was way south in Maryland: the Conowingo Bridge.

Fords across the Susquehanna were too rocky or deep for a full division or even a brigade or even a company to cross without being raked by Union cannon fire. Any craft — canal boats and ferries — were pulled to the east bank around Columbia.

In its day, the massive Columbia Bridge, as it was called, was outfitted for canal, pedestrian, rail, wagons and livestock to pass over. And freedom seekers passed through, too, when the bridge was unguarded by those seeking to catch them and return them South.

York County residents and others in the Confederate path needed a well-functioning bridge to get to Lancaster County ahead of the enemy’s advance.

Initially, the bridge company continued to charge fees for crossing, causing a massive logjam in Wrightsville. Finally, the bridge company lifted the tolls and all kinds of conveyances and people on foot jammed through the long tube to the Columbia side and safety. Safety, that is, unless the Confederates took the bridge and planted their flags on Lancaster County soil.

Rebels fire on town

Gordon started his day at the farmhouse in the village of Farmers on the Gettysburg Pike, past today’s York Airport, where he had accepted York’s formal surrender.

He would march the 10 miles to York, pull down the 35-foot American flag flying atop the 110-foot pole in the borough’s Centre Square and head toward the Susquehanna.

He arrived in Wrightsville equipped with a precise map of that town’s defenses, extracted from a bouquet of flowers a girl had given him in York.

On a hill outside Wrightsville, he sent his men around both flanks of the thinly defended Union lines. And his cannons opened up on enemy lines and thus the town, some of the 40 shells fired dropping into the Susquehanna.

One shell decapitated a Black defender, a man unknown today who had first dug entrenchments and then picked up a gun. He would be the only fighting man to die in the battle.

The combat-hardened Confederate troops overwhelmed the cobbled-together bunch of defenders, who clanked across the bridge.

The defenders clear, it was time to stop the Confederate advance by dropping that span.

Fire spreads both ways

But the span did not drop.

The mines in those arches exploded as planned, but without the intended effect. One account says the span lifted and then settled right where it was.

Confederate infantry started appearing in the Wrightsville bridge entrance, and there was no time to cut those arches.

But there was time for plan B. Jacob Miller and his fellow workers gathered boards and other combustibles and doused the wood with coal oil and kerosene. They lit the pile and headed east.

The flames followed them a span at a time.

Except for sparks and other flames heading west that caught a Wrightsville lumber company, houses and other buildings on fire.

Fire a common theme

There were many heroes that day in Wrightsville and Columbia.

The Northern defenders who fought to protect the bridge would be counted in that number and particularly the Black volunteer who died in the trenches.

A woman in Wrightsville, Mary Jane Rewalt, thanked Gordon and his fellow officers for helping douse the flames — the Confederates were concerned that they would be called to account by Lee for disobeying orders not to destroy private property. When Gordon and other grizzled Confederate officers asked about her position on the war, she stood squarely against these powerful men. Her husband was away in the Union Army, and she was a Union woman.

And then there’s Jacob Miller, the carpenter.

His story that day is full of ironies, and fire is a common theme both individually and in this theater of war.

Miller, facing capture, stared down the enemy, one of the last of the bridge’s defenders to leave its west end. He was part of that quartet who bravely stayed behind to stop a sweating Confederate division cold on the Susquehanna’s west shore.

He had everything to lose, but there he was risking everything before torching the bridge. That is, a carpenter with little in his pocket risked liberty or life.

In contrast, York’s town leaders had everything to keep and sought to keep everything, approaching Gordon in his camp and surrendering the town to reduce the risk, unfounded as it turned out, that it would be burned. In other words, men with a lot in their pockets sought to keep them full.

In the process, York lost its honor, civilians seeking out the enemy in a theater of war. Miller and the bridge’s defenders gained honor for their towns, standing tall — or sitting coolly — in the face of the enemy.

The rebels did not burn York and were forced to put out flames in Wrightsville before countermarching on June 29 to York and then to Gettysburg.

Many Confederates who felt the cool water of the Susquehanna died from the blazing muzzles and amid intense smoke from Union guns on Cemetery Hill.

Sources: Susquehanna Heritage’s RiverRoots blog; Scott Mingus’ “Flames Beyond Gettysburg”; Jim McClure’s “East of Gettysburg.”

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: When the Confederates raided York, Pa. everyone played with fire