Confronting a legacy of hate, a rural SC town tries to make sense of trans teen’s murder

Promise Edwards looked out at the crowd of about 70 people who gathered at the community center Monday night and for the second time in nearly 20 minutes she offered both gratitude and regret.

“If Jacob would have had one single ounce of support and love in his life that he has right now, we would not be standing here today,” Edwards said.

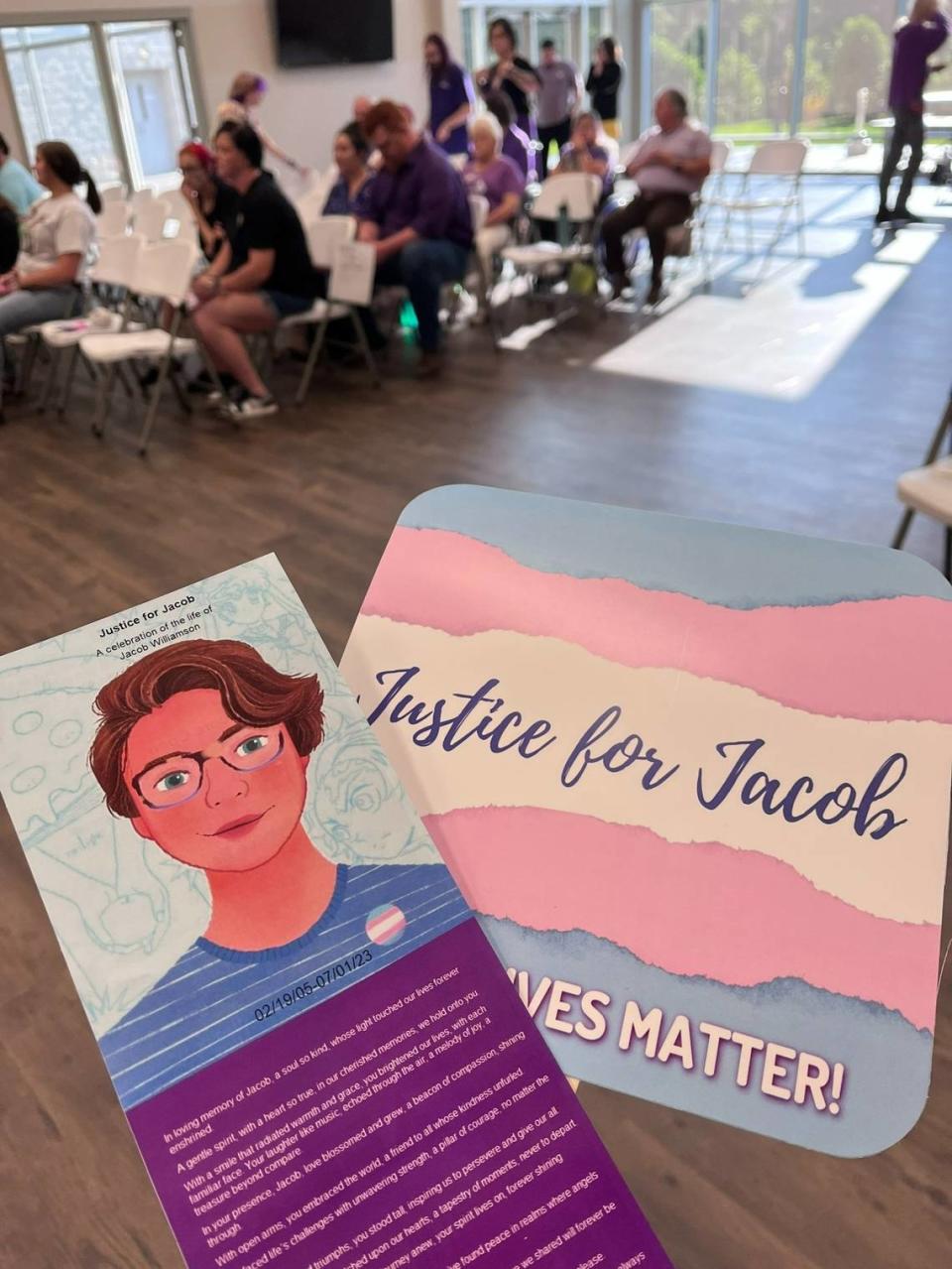

In front of her, the seats in Jacob Williamson’s hometown of Laurens, South Carolina, were filled with friends, family and people who never knew the 18-year-old. Many wore purple T-shirts or had hair streaked with shades of plum, a color symbolizing support for LGBTQ+ youth.

Several never met Williamson, but they had heard his story.

Williamson’s body was found July 4 on the side of a road in Pageland, South Carolina, roughly 8 miles from where 25-year-old Joshua Newton lived in Monroe, North Carolina. Police have charged Newton with first-degree murder and obstruction of justice in Williamson’s death, and arrested Newton’s girlfriend, 22-year-old Victoria Smith, in connection with the killing.

Williamson had been living as a transgender man for about a month when he went to meet Newton, whom he first connected with online, Edwards said.

Police say the killing is not being investigated as a hate crime.

His family and friends say that Williamson might not have been killed because he was transgender, but he died because he was transgender. It’s a small distinction with a gulf of understanding in between.

“All of the love and support that Jacob is getting right now in his untimely death could have prevented this from ever happening,” Edwards told the crowd.

He felt shunned by his family, Edwards said, and began living with her, a longtime family friend, near the end of May.

Edwards and Williamson’s mom, Brittney Patterson-Shealy, have been friends since grade school. But they “haven’t really spoken” in months, Edwards said, splitting over Williamson’s transition.

Everything has become complicated.

She was not invited to Williamson’s funeral, which was held last week in Williamson’s birth name, because she “refused to stop saying ‘Jacob.’” In an interview for an article jointly reported by the Observer and The State, Patterson-Shealy made clear that she only uses Williamson’s birth name and feminine pronouns.

Williamson never knew that organizations like PFLAG Spartanburg existed, Edwards says, but it helped organize Monday’s vigil with the help of Uplift Outreach Center, another Spartanburg organization that aims to make LGBTQ+ youth feel welcome.

“I feel that the sequence of events that led up to his death could have had a very different outcome if he had just been accepted from the beginning,” said Amberlyn Boiter, president of PFLAG Spartanburg. “He would have been less likely to try to find that love and acceptance somewhere else.”

Williamson was accepted by a small circle of friends and family, but did not feel accepted by the larger community he was a part of in his conservative, small Southern town. And he was still searching for love. The date he expected to go on last month before being killed would have been his first.

‘Somebody’s life is gone’

Laurens once gained notoriety because it was known as the home of The Redneck Shop, the self-proclaimed “World’s Only Klan Museum” that sold white-nationalist and neo-Nazi paraphernalia until it closed in 2012. The town, itself, is named after a former prominent slave trader.

More recently, Laurens has become known as the South Carolina city that earlier this year reelected the state’s first openly gay mayor.

It has an undeniable racist past that has led to a legacy of hate, but it’s also accepting enough to disregard a local politician’s sexuality.

Nathan Senn wants to be careful to not make connections where there might not be any, so he speaks with long, thoughtful pauses. The mayor of Laurens, a city of about 9,000 people, has been told that Williamson’s murder was not a hate crime. In fact, he didn’t know Williamson was transgender at first. The county weekly newspaper’s July 5 headline said, “2 charged in death of 18-year-old Laurens woman.” The report was based on the victim’s sex and name given by police.

Senn is worried the focus on Williamson’s gender identity overshadows the starkly horrific details of the murder, itself: A teen was lured from home by someone he met online and killed.

“Because these are such divisive times and because gender identity doesn’t seem to be a factor in this beyond just as a descriptor of the person who tragically passed away, this becomes a story that could do more to divide than bring people together,” Senn said.

“And I think the last thing I would want as a community leader is to cause division or drum up publicity as a result of a tragedy.

“My concern is just that a story that is truly a personal tragedy becomes something that’s centered around identity and identity politics, honestly. Ultimately, I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that somebody’s life is gone.”

But the stories are intertwined, transgender advocates say.

In 2023, 79 anti-transgender bills have been passed across the country, according to Trans Legislation Tracker. S.C. Sen. Danny Verdin, a Republican who represents Laurens County, was one of the primary sponsors on a South Carolina bill earlier this year that proposed banning gender-transition surgeries, hormone therapy and puberty blockers for people under the age of 18. The bill has not yet come up for a vote in the state Senate.

Edwards said Williamson came to her house because he knew she would accept him; she is bisexual and has made a point to tell everyone around her that her home is a “safe space.” There are not many other places in Laurens — or South Carolina — that make the same proclamation.

Boiter, the PFLAG Spartanburg president who is transgender, said she grew up in Pickens County, near Greenville, South Carolina, and understands the community where Williamson was raised.

“The fact that I was born in such a rural county is part of what kept me in the closet for over three decades,” she said.

No Laurens elected officials — except the mayor — have made public statements about Williamson’s death. Senn helped secure the site for the vigil, The Ridge at Laurens, but he did not attend. State representatives were invited, Boiter said, but also did not make an appearance. Laurens Police Chief Keith Grounsell was the only visible city official in the crowd.

‘They’ve buried so much’

Regan Freeman, who attended the vigil, had heard Williamson’s story reported nationally but didn’t know the teen was from his home county until last week.

“They’re so committed to making Laurens look like a happy, small-town place to grow up in that they’ve buried so much,” Freeman said. “They’ve buried so much. And that’s been the case for centuries.”

He grew up in nearby Clinton without knowing anything about the racist history of the county seat. When he learned in college about lynchings in Laurens County that he was never taught about as a child, he was inspired to connect with Rev. David Kennedy. Kennedy is the pastor of the New Beginning Missionary Baptist Church who now owns the Echo Theater, the building where The Redneck Shop once operated.

Freeman is now the executive director of The Echo Project, the nonprofit working to transform the former Echo Theater into an education center, museum, and community center. Freeman said he’s hopeful the center can open in about three years if full funding is secured.

He regrets that it wasn’t open for Williamson.

“We believe we can fight that kind of legacy of hate and of fear,” Freeman said. “We’re making progress, but I am sorry to say that we weren’t around (for Williamson). People deserve community and they deserve a network. And it just breaks my heart that this happened.”

Laurens, Freeman says, is still working to shed its past. Its racist history, of course. But also its unwillingness to accept anyone different. The city might have elected an openly gay mayor, but Senn did not make his sexuality a focus of his campaign. He won reelection in a runoff in March by garnering 54% of the vote.

“Nathan never really made a point that he was gay in this campaign,” Freeman said. “So that’s true that they did this (elected him), but it wasn’t like a referendum on, ‘Should we have a gay mayor?’ It was just Nathan.”

No black-and-white answers

Edwards said she woke the morning of Williamson’s vigil feeling sad. She was remembering all the things she missed about Williamson: His goofy sense of humor, his outgoing happiness, his love of anime and his generous, kind soul.

By the time the vigil was over Monday evening, after she had spoken for 20 minutes about her community’s need for acceptance and about the dangers of online dating, she said she felt “a million times better.”

“When I looked out and I saw all these people here that were just loving, they just gave me a little bit more hope that there are still some people that care,” Edwards said. “I’m proud of the amount of people that came out to show their love and support.”

But she also was careful to be inclusive of anyone who might use Williamson’s birth name and female pronouns — presumably, people like his parents. It’s all so complicated.

“When they speak, they’re speaking from memories that they know,” Edwards said. “And it is not a disrespectful thing. So I ask that you guys understand that all of us have memories, whether that is with ‘her’ or with ‘him.’”

The vigil served as a remembrance of Williamson, but it also was a clear plea for acceptance of transgender individuals, in general.

Speaker after speaker talked of Williamson’s gender identity and the transgender community’s feeling of disconnection and otherness. How a political focus on gender identity is fanning the flames of hatred toward a group of people and causing the tragic death of one teen from Laurens to become centered around a singular aspect of who he was.

Boiter knows there are still questions about what led to Williamson’s death. Because Williamson might not have been killed because he was transgender, friends and family say, but he died because he was transgender.

“So often people want a very black-and-white answer on things,” Boiter said.

What she left unspoken is that few things in life are ever that clear.