Congress in 1777 acted with urgency - America and their lives depended on it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Editor’s note: Another in a series of occasional columns about York County’s role in the American Revolution, with upcoming American foundational 250th anniversaries in 2026-28 in view.)

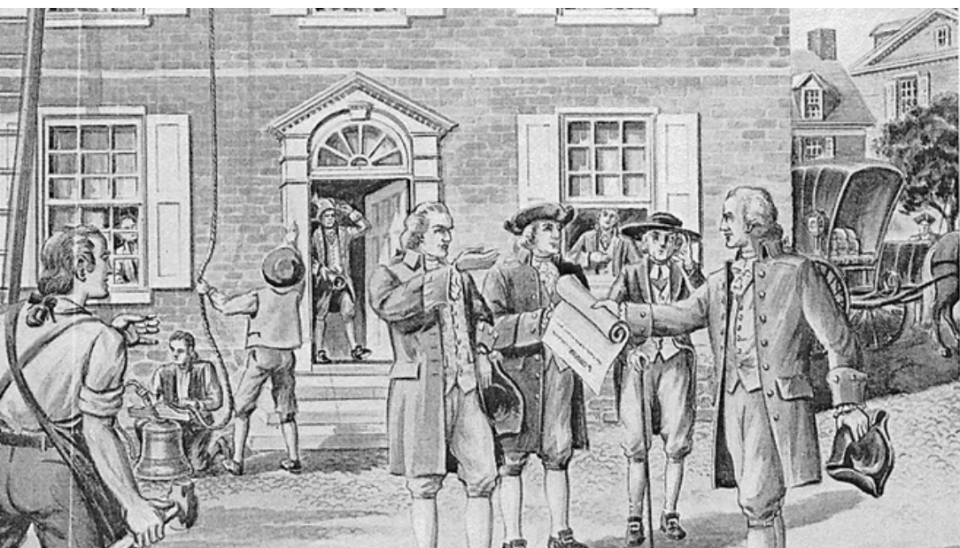

When the Continental Congress met in York in 1777-78, the 64 delegates offered maybe 64 ways to build a fledgling nation.

And often without grace.

“(S)ome sensible things have been said, & as much nonsense as ever I heard in so short a space, I have not contributed to either," South Carolina’s Henry Laurens wrote his son, John, shortly after Congress convened in this Pennsylvania frontier town.

Accord was in short supply until these statesmen realized that their hats and collars could be replaced with blindfolds and ropes.

For example, Congress approved one of the 13 provisions that almost overnight flipped the Articles of Confederation from a document authorizing a strong federal government to one that favored autonomy of the 13 individual states. That article remained in this constitution, a framework of government that consumed the delegates in their first month in York in the fall of 1777.

Further, delegates from small states — Maryland and others with limited size or population — contested a constitution that favored Pennsylvania and other large states.

They disagreed on whether Congress would assess the states for Revolutionary War debt based on property or per capita, the latter counting enslaved people. They chose to assess property – land, buildings and improvements

Intense discord on weighty issues, to be sure, but the Continental Congress somehow approved the Articles of Confederation on Nov. 15, about 45 days after arriving in York. They simply needed France as an ally or lose the war to Britain and, thus, their nationhood. And perhaps their lives in the gallows on charges of treason.

This urgency offers lessons for our state and federal lawmakers who often collapse into political gridlock when they are most needed in this a Whac-A-Mole world fill with unrest and violence.

Taken as a whole, the Continental Congress’ story in York County is an example of effective action in a national emergency.

Getting down to business

Let’s consider what the Continental Congress got done in one 30-day sample starting on Oct. 31, 1777:

Learned about the British surrender at Saratoga, New York, touted by some as the turning point of the American Revolution. Until that upstate New York fight, American victories in pitched battles were rare.

Lost its president, John Hancock, who went back to Massachusetts on furlough.

Elected a new president, Henry Laurens, who would serve in that post through Congress’ return to Philadelphia on June 30, 1778.

Drafted a Thanksgiving proclamation to observe the decisive victory in Saratoga. The Dec. 18 observance was the first of seven days of Thanksgiving and Praise in the American Revolution.

Lost two more leaders to furlough: the Adams cousins, John and Samuel. That cold and dark winter, the Continental Congress counted a dozen or fewer delegates, as many preferred the conveniences of home. Only Laurens and two other delegates served all 271 days in York.

Reorganized something akin to today’s Defense Department, then called the Board of War. Gen. Horatio Gates, victor at Saratoga, would become its first chairman, showing some in Congress and the military’s confidence in him and ambivalence toward George Washington. Some viewed this as part of a plot, whether real or imagined, to oust Washington and replace him with Gates, known to history as the Conway Cabal.

Recalled Silas Deane as American negotiator in France and appointed John Adams to replace him.

Adopted the Articles of Confederation, America’s first framework of government. That constitution would serve America through the war that ended in 1783. Its weaknesses, many coming as concession to the states’ rights advocates, emerged in the postwar years, prompting enactment of the U.S. Constitution in 1789.

Approved a French translation of the Articles of Confederation.

The Revolution turns

The two major pieces of news — the Saratoga victory and Articles of Confederation — helped bring France onto America’s side. The French now knew that the Continental Army could fight on the field, and the Articles proved that Congress could resist fighting among themselves.

Much is made of the year 1776 as a turning point in the American Revolution. Historian David McCullough wrote a book just on that year.

But more attention should be given to the fall, winter and spring of 1777-78.

No Articles. No Saratoga. No treaties with France.

Most scholars say America would have fallen to the British without French support, which became official when Continental Congress ratified the treaties in early May 1778 in York.

Poster boy for division

Some will say that the political world was not as logjammed then as today, that political parties were not yet formed, much less entrenched and the nation was far less balkanized.

Well, political parties spent part of their stubborn infancy in York in the form of the division between advocates for strong central government and states’ rights. And the states’ rights proponents were winning the day, meaning the United States was really carved up into 13 parts.

North Carolinian Thomas Burke was the poster boy for this division between states’ rights and federalism. Burke was the leader of the movement that flipped the Articles of Confederation to a states’ right framework, something the U.S. Constitution remedied a dozen years later.

“It appeared to me that this was not what the States expected,” he wrote to North Carolina’s governor Thomas Caswell, “and, I thought, it left it in the power of the future Congress … to explain away every right belonging to the States, and to make their own power as unlimited as they please.”

Interestingly, Burke was an unlikely delegate to make such a change.

He was as unlikable as any of the national political leaders on the scene today.

It was late one Friday night in the spring of 1778, for example, that Burke brought the Continental Congress to a halt. He could not convince his weary colleagues of a wording change involving prisoner pardons brought forth by Washington.

He walked out of York’s Centre Square courthouse, leaving Congress without a quorum.

A messenger was sent to call back Burke, and he brought back the North Carolinian’s response: “Devil take him if he would come; it was too late and too unreasonable.”

His fellow delegates, in turn, resolved that Burke’s walkout was, in effect, contempt of Congress.

Burke’s response captured the tenuousness of a constitution that failed to find a balance between state and federal authority.

Congress, Burke said, had no power over him and he was beholden only to his home state. In other words, Burke worked for North Carolina, not for Congress.

Of course, his peers in Congress countered that this thinking was dangerous. It struck at the very existence of the House.

Some — maybe many — statesmen in York’s Continental Congress, had to adopt the Articles of Confederation, though disagreeing with some of its 13 Articles. They simply needed an allied France to preserve America.

They just had to turn the other cheek to avoid blows from the likes of Thomas Burke.

In the end — and there’s another lesson here for today — decency, common sense and statesmanship won the day.

That was embodied in this letter from Richard Henry Lee of Virginia.

"(I)n this great business ... we must yield a little to each other, and not rigidly insist on having everything correspondent to the partial views of every state," he argued. "On such terms, we can never confederate."

Sources: James McClure’s “Nine Months in York Town,” Journals of Continental Congress.

History storyteller event set for Dec. 7

An evening of storytelling about York County history is set for 7 p.m. Dec. 7 at Wyndridge Farm near Dallastown. For tickets and other information about the evening, go to www.yorkhistorycenter.org/event/history-storytellers.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Congress in 1777 acted with urgency - America depended on it