Conservationists work to protect sperm whales off Caribbean island

In December, nearly every member country of the United Nations pledged to protect at least 30% of the world's land and sea by 2030 to reverse the damage done by humans and protect vulnerable species.

One of the animals at risk is also one of the largest in the ocean and among the least understood. Sperm whales are not the predators of Moby Dick legend. They have brains six times larger than ours and spend most of their lives in the darkest depths of the ocean. It is difficult to describe their size without comparing them to a school bus.

Last month, we traveled with National Geographic Explorer Enric Sala to the Caribbean island of Dominica, where he's proposing protections for the hundreds of sperm whales living there.

But first we had to find them.

Curt Benoit: You guys ready? Go, go, go. Go, guys, go! Look in the water coming straight to you.

Most of Enric Sala's dives don't start like a fire drill… even though he has spent thousands of hours underwater as an explorer.

Curt Benoit: Look down and in back of you.

We came face to face with a pod of whales -- but these are not the whales we traveled all this way to see. They are pygmy killer whales known to threaten sperm whales. And because they are here, the sperm whales are not.

These killer whales can grow up to eight-and-a-half feet in size.

Sala told us seeing them up close almost never happens.

Cecilia Vega: You've never been able to get into the water with one of these. They're that elusive.

Enric Sala: They are very elusive.

Cecilia Vega: W-- why is that? Why do you not see them?

Inside Cecilia Vega's first 60 Minutes story on sperm whales

Enric Sala: They are very smart. They hunt like wolves. They hunt in groups. And they don't care about interacting with humans. They are after the prey

We were off the coast of Dominica -- a country in the eastern Caribbean.

Residents call it Nature Island. Those rainforest-covered volcanic peaks drop thousands of feet down to the seafloor below - which is why hundreds of sperm whales live in these waters. They are one of the deepest diving mammals on the planet.

They are mostly females here -- families made up of grandmothers, mothers and daughters who stay together for life…nursing and raising their young.

When Enric Sala was here in December, his National Geographic team filmed this.

It is a pod of sleeping female sperm whales– vertical giants up to 40 feet long suspended near the surface…their nap lasts only about 15 minutes…until the whales are ready to dive again in what can be an hour-long journey for squid thousands of feet down.

Even to researchers -- why they sleep like this is one of the great mysteries.

Cecilia Vega: What's it like to be in the water with them?

Enric Sala: Magical.

Enric Sala: We have, in our minds, the legend of Moby Dick: these nasty, aggressive animals. But you jump in the water, and they are so docile and gentle. They have never attacked humans, and they are so curious, especially the babies. So, it's one of the most amazing wildlife encounters that one can have on the planet.

Cecilia Vega: Your official title is "Explorer-in-Residence." Not bad.

Enric Sala: It's an oxymoron. Explorers are not supposed to be "in residence."

Cecilia Vega: That's true you're not supposed to be sitting in one place.

Cecilia Vega: What does that mean, to be an "explorer" in the year 2023?

Enric Sala: Very different from what an explorer of the 19th century was. I can dedicate my life, and work with an amazing team of scientists, policy experts-- filmmakers, storytellers to work with local communities, governments, and Indigenous peoples to assess the health of ocean places and help to protect them.

He grew up north of Barcelona, Spain near the coast-- his first dive was in a marine reserve.

Enric Sala: It drove everything that I have done afterwards. If we give the ocean space it can heal itself.

Sala moved to California, where he was a professor of marine ecology for seven years at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Cecilia Vega: You have had a long career in academia, at a top university, and you tried that and decided "not for me." You walked away.

Enric Sala: I walked away because my job was to study the impacts of humans in the ocean, the impacts of fishing and global warming. And one day I realized that all I was doing was writing the obituary of the ocean.

Cecilia Vega: Writing the obituary of the ocean?

Enric Sala: Yeah. I felt like the doctor who's telling you how you're going to die, with excruciating detail, but not offering a cure.

Cecilia Vega: Have you found that cure?

Enric Sala: There is one solution that is proven, it's a success story everywhere in the world. Which is-- marine reserves, or marine protected areas: areas where damaging activities are banned, and marine life can come back.

He founded the Pristine Seas Project in 2008. It combines sea exploration, scientific research and public policy…and has worked with 17 countries to turn these large swaths of the ocean into marine protected areas.

In Dominica, scientists estimate the sperm whale population declines by 3% each year.

Sala says a preserve would protect them from their greatest threats: not those pygmy killer whales we saw or whaling, which has been banned for decades…but plastic trash, ocean noise pollution and ship strikes.

Cecilia Vega: If they continue with the status quo here, what happens?

Enric Sala: If nothing is done, the population will probably continue declining, so reducing those threats hopefully will allow the sperm whale population to rebound. And the more whales there are, the more benefits Dominica and the local communities will obtain.

Hurricane Maria devastated those communities in 2017.

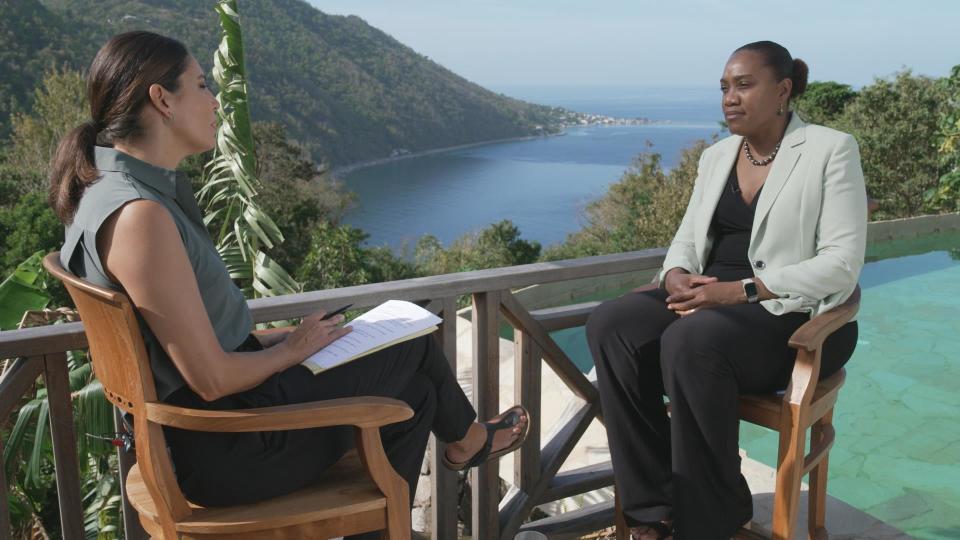

Today the island is continuing to rebuild and prepare for the future…Francine Baron heads the agency in charge of that effort.

Cecilia Vega: What was it about Hurricane Maria that made the leaders of this country say, "We have to do something, we really have to act"?

Francine Baron: We suffered the equivalent of 226% loss of GDP. So we could see the trend, and we realized that we needed to become much more resilient.

Cecilia Vega: When Enric Sala came to you with this idea of creating-- a sanctuary for these whales, what was his pitch to you?

Francine Baron: We see whale-watching as an important part of our tourism product, and it's something that needs to be protected. And-- the idea of creating-- greater protection for the whales is something that Dominica is very open to. And we were very pleased with the suggestion that Enric made to creating-- a recognized sanctuary for the whales.

Enric Sala compares it to a model that has worked in Rwanda… where protecting mountain gorillas helped bring tourism dollars to the local economy.

Cecilia Vega: You going to find us some whales?

Curt Benoit: Sure.

Cecilia Vega: Alright.

Captain Curt Benoit was born and raised in Dominica and has been in the whale tourism business for more than two decades. We set out on his 38-foot Lady Rose from a small fishing village on the west coast.

Our government permit to swim with the whales was good for six days.

Captain Benoit uses a homemade device that picks up the distinct clicking of sperm whales as far as 11 miles away.

Curt Benoit: We got whales in the south.

Every three miles, we checked to see if we were getting closer.

Curt Benoit: Come to Papa. Daddy's here.

Cecilia Vega: Tell me about this really high-tech device you've got here.

Curt Benoit: You have an underwater microphone which picks up sound from 360 degrees. So what I did: I take a salad bowl with Neoprene. So the hydrophone is kind of hidden, so as it goes out, it actually brings you straight to wherever you hear the sound.

Cecilia Vega: So this is a salad bowl from your house.

Curt Benoit: Yes.

Cecilia Vega: What do the whales sound like?

Curt Benoit: (snaps fingers) It's like—a horse is gallopin' on a hard surface. So if you hear several of them, that means there's a lot of whales there.

Curt Benoit: Let's keep on going. I'm going to find these guys.

Cecilia Vega: Alright.

On the second day, a water spout.

Cecilia Vega: See it! It's right here. Look guys! See him? You can see his top, look at him, oh my gosh.

What a sperm whale did to a 60 Minutes cameraman that will help the ocean

Males here live with their families until their teen years. Then they roam mostly alone, swimming thousands of miles away. Caribbean male sperm whales have been found as far away as Norway, returning here only to mate.

Cecilia Vega: Our cameraman got lucky enough, or unlucky enough, to have the whale poop on him.

Enric Sala: So the whales go down, they hunt squid, they come back to the surface, they breathe, they rest, and they poop. And that poop is full of nutrients which fertilizes the shallow waters.

Cecilia Vega: So a good thing, I guess.

Enric Sala: It's a good thing.

Curt Benoit: Come on people, we're looking for spouts.

But our luck…didn't last.

Curt Benoit: Ok guys, nothing is here.

We spent the next day searching for sperm whales…and the next..

Cecilia Vega: Nothing at all?

Curt Benoit: Nothing at all.

And the next…not a single click.

Curt Benoit: OK guys, it's pretty quiet.

And then -- in the last hour, of the last day of our trip…

Curt Benoit: There are lots of animals in the area guys --

Curt Benoit:….oh, they're coming back. But I'm getting sounds of 360 so that means the whales, we are above them…we are right there.

First mate: There she blows! There she blows! …Go, go, go!! And stay there, it's coming to you…

Curt Benoit: It's coming to you! It's coming to you!

We jumped in the water and a young female swam right to us… she came within feet… at first, her size was terrifying.

She made a sound like a creaking door hinge -- it's one of the ways whales communicate and socialize.

With eyes on the side of her head -- she stared right at us…

She had squid in her mouth -- left over from lunch thousands of feet below…

She stayed and rolled around -- and her jaw was wide open. She was using echolocation…bouncing those clicks off of us trying to figure out what we were.

Cecilia Vega: You could hear the clicking. You could hear her. Once you were really close to her, you could "t-t", you could hear that so well--

Enric Sala: Very loudly, I could feel it in my bones.

Cecilia Vega: Uh-huh. You grabbed my hand. You could tell I was nervous.

Enric Sala: I was excited too.

Cecilia Vega: You were?

Enric Sala: They are huge. You have to respect them.

Cecilia Vega: You have to respect them. There is a sense of awe that comes with being in there. She was lookin' right at us.

And she left us a souvenir.

Dennis Dillion: A piece of squid.

Shane Gero: Sperm whales live in…

Shane Gero is another National Geographic explorer...he started the Dominica Sperm Whale Project and over the past 18 years, he's identified more than 35 families.

Cecilia Vega: Did you recognize the whale that we saw?

Shane Gero: The animal you met belongs to the EC2 clan, the other clan of whales that we've known exists in the Caribbean, but we haven't seen all that much. And those groups identify themselves by making specific patterns of clicks, called codas.

Shane Gero: It's a part of who they are, where their grandmother grew up. And so it really ties the animals and the place together.

Cecilia Vega: What does the coda of the EC2 sound like?

Shane Gero: They make the 5R3 coda. And it sounds like this (clapping). Five slow clicks.

Shane Gero: And she came up to you and made this 5R3 coda, saying, "I am from the EC2 clan. Are you?"

Cecilia Vega: She was rolling around, and she kept coming back. But is that me, assigning human characteristics to a whale? Or is she actually a playful animal?

Shane Gero: These are the animals that are holding the largest brain to ever exist, maybe in the universe. And they use that to-- for complicated thinking and-- behavior Absolutely, this was an animal that was playful. And that curiosity of the animal actively coming towards you just shows that this is an animal that's investigating something in its world.

Back on the dock…

Enric Sala: There is a treasure here…

Enric Sala says, it's that world he's trying to protect.

Enric Sala: Being in the water with sperm whales is a magical experience, there's something spiritual there, this is more than science and data.

Enric Sala: The sense of awe and wonder that is unavoidable when you are in the water with these gentle giants.

Produced by Michael Rey. Associate producer, Jaime Woods. Broadcast associate, Eliza Costas. Edited by Sean Kelly.

Sharks tracked off Atlantic coast by OCEARCH | 60 Minutes

Yannick Nézet-Séguin: The 60 Minutes Interview

Sperm whale protection focus of marine sanctuary creation in Caribbean | 60 Minutes