'I was considered less than' Black 81-year-old remembers 1960 DeLand lunch counter sit-in

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

DELAND — When Joyce Cusack was growing up in west Volusia County, Black and white babies were born in separate wings of Halifax Hospital, and skin color determined where people lived, went to school, worshipped, worked, dined, socialized, shopped and were buried.

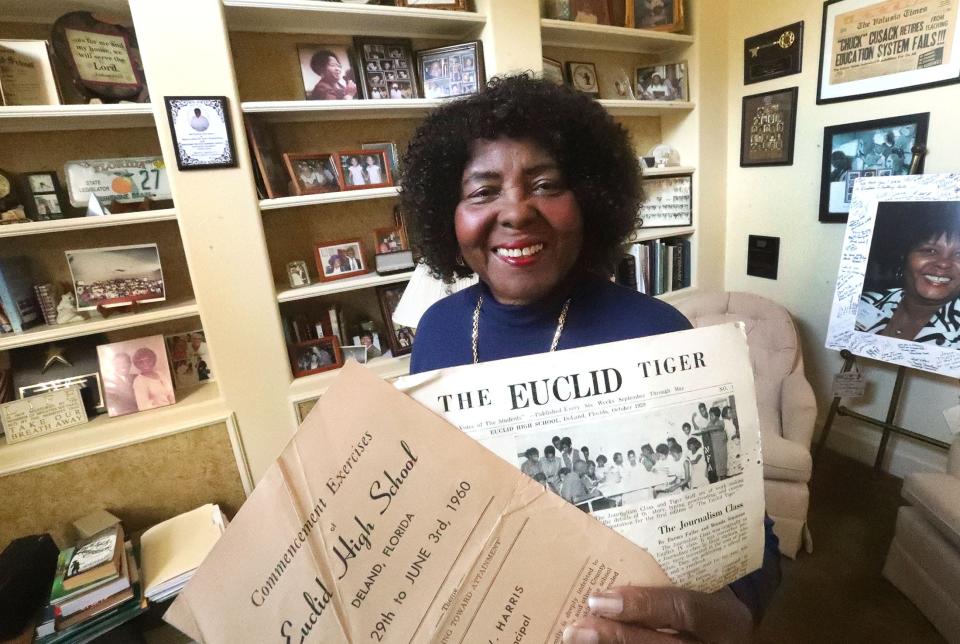

By early 1960, when Cusack was a 17-year-old high school senior at the only DeLand school Black kids could attend, she and dozens of her classmates were fed up with going to downtown lunch counters and being ordered to drink their bottles of Coca-Cola outside while white people were able to sit down inside and enjoy a chilled soda, milkshake or sandwich.

So about 25 or 30 of the Black teens gathered on Woodland Boulevard one afternoon, marched to the Woolworth's store, crowded around the lunch counter and tried to order something from the soda fountain that they could drink inside. It became their daily routine for a week in February 1960, being refused service while a line of police officers separated them from angry white people hurling racial slurs and urging police to let them deal with the kids who dared to break the rules of racism.

A few months later, the DeLand Woolworth's made the then-radical decision to let anyone, regardless of race, eat and drink at the counter or in one of the nearby booths. The young protestors had won.

"We did it to raise the consciousness of people that this is not right," said Cusack, who's 81 years old now and a grandmother. "I was considered less than. What does that do to your self-worth to be told you can't sit there?"

At noon on Feb. 25, Cusack and some of her fellow Euclid School protestors are going to gather again outside the still-standing Woolworth's building and another building across the street where they staged more lunch counter protests a lifetime ago. Some live in other cities and states now, but they'll come back to their hometown to witness the dedication of bronze plaques placed on each building to memorialize their brave actions that kicked down a local Jim Crow law.

"It's very important we document the history of this city, state and country," Cusack said. "I want it to be an event that bridges people to say 'this is part of the history of DeLand.' "

The Sunday afternoon reunion will also be a chance to talk about what else the protestors did over the past 64 years to break down racial barriers, what has changed in the world since then – and what's still the same.

Toppling more racial barriers

Despite 20th-century constraints on Black people and women attempting to hold down Cusack, she soared in life. She went to college, became a registered nurse, and in 2000 was elected to the Florida House of Representatives – the first time voters sent a Black Volusia County resident to Tallahassee to represent them.

She smashed that racial barrier with a constituency that was about 90% white.

"Those same folks (at the lunch counters in 1960) who were saying 'let me get to them,' their grandchildren were saying 'let me get to the polls and vote for her,' " Cusack said.

In 2006, during her third term as a Florida state representative, she served as the Democratic Leader pro tempore of the Florida House, which made her the number two-ranking Democratic member.

After eight years in Tallahassee that maxed out term limits, she served on the Volusia County Council in the at-large post from 2010 until 2018.

She has also been a delegate at four National Democratic Conventions, and she met former President Barack Obama at his 2009 inauguration. She also attended a Christmas party at the White House when Obama was president.

Scared but determined

Cusack was born in New Smyrna Beach in 1942, but she lived in DeLand from the time she was two or three years old. Her parents had split up, so it was just Cusack, her sister and her mother living with her grandmother.

They lived in DeLand's southwest corner, as many Black people in that city did in the early 20th century. Cusack's grandmother owned a popular restaurant called Smitty's Café that was in the heart of DeLand's Black business district.

Most kids walked to school, and the Black children who lived farther north had to pass through downtown DeLand to get to the first through 12th grade Euclid School at the corner of Euclid and Adele avenues. They were the ones who were most annoyed that they couldn't hang out at the lunch counters they strolled past every day, Cusack said.

Black people could shop and buy something in Woolworth's or McCrory's department stores, which were located across the street from one another on Woodland Boulevard at New York Avenue. But Blacks couldn't linger at those two stores' lunch counters once they paid for their food and drinks, Cusack said.

The kids were determined to stand up to the blatant racism, but they were old enough to know what could happen to a Black person who bucked things in the 1950s and 1960s South.

"I was scared as hell," Cusack said. "All these big white men were trying to get at us. They were yelling and saying 'let us get to those (n-word)."

Cusack and her friends had taken drinks from water fountains in JC Penney marked for whites only many times, and they would laugh as they darted away with a white person chasing them. But they had never staged a public protest.

Their parents and grandparents begged them not to do it. The adults were mainly afraid for the kids' safety, but some of the mothers were domestic workers for white people, and they didn't want to lose their jobs.

Booker T. Washington joins in

To protect their families and themselves, the teens never gave their real names if anyone asked during the sit-ins. They would instead give the name of an accomplished Black person, such as Mary McLeod Bethune or Booker T. Washington.

They defiantly sat down on the stools and in the booths inside the Woolworth's eatery, and after the lunch counter abruptly closed, the kids went across the street to McCrory's and did the same thing.

"The staff was in an uproar," Cusack said. "They had no idea we were coming. It was the buzz of the time."

Even more teens joined in on the second and third days of the protests.

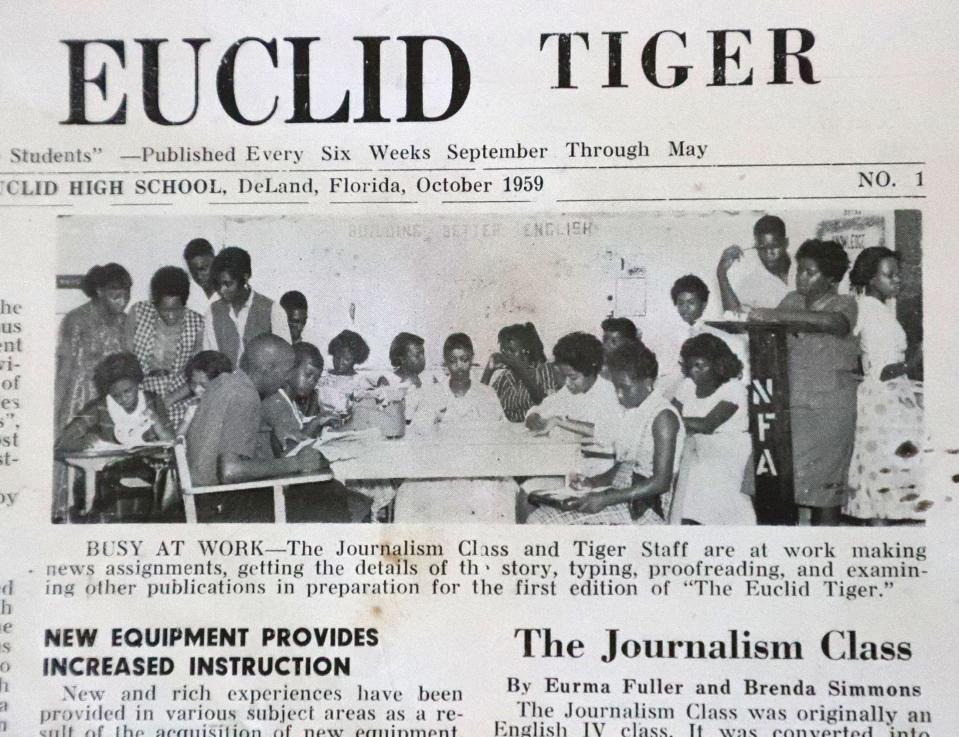

A few kids stopped going to the daily sit-ins, but Cusack was among those who finished what they started. Cusack was a member of her high school's student government, serving as president at one point, and she was the managing editor of the school newspaper.

"I was a leader and I didn't even know it," she said.

The history of lunch counter sit-ins

The west Volusia County teenagers were not the first in Florida or the United States to stage a lunch counter sit-in. Some credit the July 1948 drug store protests in Des Moines as the first.

Baltimore held lunch counter protests in 1953. In July 1958, young Blacks held sit-ins for weeks at the Dockum Drug Store in Wichita, Kansas. A month later more drug store sit-ins were held in Oklahoma City.

In September 1959, both white and Black people began sit-ins at Miami department stores that refused to serve Black patrons at their lunch counters.

On Feb. 1, 1960, college students began non-violent protests at the Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., that persisted for six months and made national news.

The DeLand protests came next, beginning on Feb. 9, 1960. Shortly after that, students at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee began lunch counter sit-ins.

The protests were spreading across the South in early 1960, and on March 2 a dozen Bethune-Cookman College students staged a peaceful lunch counter sit-in at the Daytona Woolworth's on Beach Street.

It was mainly Black college students holding the sit-ins, some of whom were guided by the Congress of Racial Equality, a civil rights organization that pioneered the use of nonviolent activism.

"They were young, and they were all hyped up with the freedom movement," said Leonard Lempel, a retired history professor who taught at what became Bethune-Cookman University and Daytona State College. "They were tired of going into town and not being able to do what they wanted. Older people accepted it. They challenged it, and it became a very effective tactic."

Daytona Beach's Black educators, businessmen, church leaders and political operatives preferred less confrontational approaches to achieve integration, Lempel said.

The local NAACP chapter wanted to organize an economic boycott of downtown department store lunch counters rather than support sit-ins. But Bethune-Cookman's president, Richard V. Moore, negotiated behind the scenes with the mayor, police chief and other city officials to integrate the lunch counters quietly, Lempel said.

"President Moore convinced these officials that the spectacle of police dragging students out of department stores would damage Daytona's tourist image," Lempel said.

An agreement was in place by early August of 1960 for small groups of Black students to sit at four major downtown department store lunch counters, order and be served, and then leave. After five consecutive days of nonviolent demonstrations, the lunch counters were open to people of all races.

'Changing things that are not right'

Several organizations, including the West Volusia Historical Society and DeLand Quakers, have worked together to raise $4,000 for the bronze plaques that will commemorate DeLand's lunch counter sit-ins inside the two buildings on Woodland Boulevard.

The former Woolworth's building at 100 N. Woodland Blvd. is now the home of the Museum of Art. The McCrory's Department store building at 101 N. Woodland Blvd. has become rented office space.

For years after the lunch counters integrated, Cusack would go back from time to time to enjoy her right to have a drink or meal like anyone else could. Sometimes she brought her two daughters.

"It was a feeling of accomplishment to take my kids to the lunch counter," Cusack said. "I preach to them all the time about changing things that are not right."

Daytona neighborhood remains troubled: Midtown, Daytona Beach's historic Black neighborhood, struggles to find a better future

While the ugliest chapters of segregation are more history than reality now, Cusack said there can still be subtle things that make people of color feel unwelcome in parts of DeLand.

"Even today you have folks watching you," she said. "These are undocumented prejudices."

Cusack said the United States still has "miles to go."

"To this day, many minorities don't feel comfortable in downtown DeLand," she said. "That's why I put my legislative office downtown. We've got to fully integrate it. We've got to raise conscientiousness of how we treat each other."

You can reach Eileen at Eileen.Zaffiro@news-jrnl.com

This article originally appeared on The Daytona Beach News-Journal: DeLand commemorating 1960 lunch counter sit-ins that sparked change