'Constant reminder that you can overcome' Families of OKC bombing victims find ways to grow

![Kyle Genzer, principal of Mannford High School in Mannford, keeps a framed flag and fragment from the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on the wall in front of his desk in his office. He is the son of Jamie Genzer, who was 32 when she died in the 1995 bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City. [Photo by Pam Olson]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/oc.FxEcdMYzC_.6MqsBGAw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyNDI7aD0xNjU2/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-oklahoman/a4f53b6d4cb111f4714569deea9efea1)

From where he sits at his desk every day, Kyle Genzer, a principal at Mannford High School, can see a shadow box mounted directly ahead of him on the wall of his office.

The box is usually the first thing he sees when he sits down to work, and the last when he leaves his office at the end of the day.

Along with an Oklahoma flag, the box contains a small rock, a fragment of what used to be the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. His mother, 32-year-old Jamie Genzer, was one of 168 men, women and children who died as a result of the bombing of the federal building on April 19, 1995.

Instead of being reminded of the tragedy, Genzer said he's reminded of her life.

"It's the last place she was on Earth. ... It's a constant reminder that you can overcome anything you're dealt. It lets me know she's always with me, as well," Genzer said.

In the past, the word "trauma" was more often associated with military combat, physical and emotional abuse or sexual assault. Dealing with its consequences has emerged as a professional specialty in itself.

Oklahoma City's Dr. Pam Fischer, a licensed clinical psychologist with more than 30 years in practice, was one of the first mental health professionals to rush from her downtown office on the day of the bombing to a nearby church to volunteer her services. Family members had been told to gather at the church to await information on loved ones.

Fischer helped pioneer early research described as "post traumatic growth," or PTG, in survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing.

In those early years after the bombing, Fischer — now an OU clinical professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences teaching medical students part time — provided counseling to survivors and family members, and those closely involved in the bombing. Her work with that trauma led her to the VA for nearly 25 years.

Seven years after the bombing, she collated responses from 226 "participants" of the blast, ranging from survivors, family members, first responders and volunteers. Her research became a chapter in the "Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice," published in 2006.

Not everyone who goes through trauma experiences post traumatic growth, a term used to describe psychological growth or strengthening. But for those who do, many report a greater appreciation of life and a renewed sense of choices and possibilities, even while still feeling psychological distress. Both experiences can co-exist, according to Fischer's research.

"What we've learned is that once you've gone through this trauma, a change has taken place. Many people develop — it's more than resilience — it's a psychological strength, as a result of realizing what they've endured. They think, 'I'm stronger than what I thought I was.'"

In her research, Fischer found that survivors of the blast and family members, especially women, reported "significantly" higher positive psychological growth than others who were surveyed.

However, Fischer found that achieving this positive growth after experiencing a traumatic event — caused by the intentional act of another — doesn't necessarily result in forgiveness of the perpetrator.

In general, females — and family members who lost loved ones — scored lower on forgiveness of Timothy McVeigh, the convicted bomber in the 1995 event.

Explanations can vary, Fisher said. But likely the timing of the study was important.

Many of the subjects were feeling significant distress triggered by the events of 9/11. Others possibly think they felt that in forgiving, they were being disloyal to those who died.

Although they reported more distress, they still experienced higher scores on personal growth and major life changes.

"They become more religious, spiritual. They changed vocations, attitudes and reported a greater appreciation of life. They often developed more compassion for others," she said.

Some family members become advocates for change, like Genzer in Mannford.

"It's the only way we learn from hatred, is to share experiences and learn from it," said Genzer, who was 14 when his mother died.

Despite his grief, Genzer has flourished through the years. The father of three sons, ages 18,11 and 7, he's head coach for the high school girls' varsity soccer team and coaches boys in youth basketball and soccer. An active member of Our Lady of the Lake Catholic Church, he's also finished his course work for a doctorate. His wife, Sara, is a manager for corporate accounting for ONEOK in Tulsa.

Every year, Genzer talks to Mannford's freshman class — usually about 125 students — about the bombing, since all were born after the 1995 tragedy. Few students know much about it.

He said talking about it to the students, essentially re-living it every year to young people who are about the age he was when his mother died gives his life a special purpose.

"I tell them how I had to grow up in the flash of an eye. I went from a 14-year-old boy and then ... planning my mom's funeral, but still not really knowing for sure how she died," he said.

"I tell them the sorrowful part, but then I focus on all the positive things that have happened, such as getting to go to OSU and Mount St. Mary Catholic High School in Oklahoma City (from which his mother graduated) on scholarships, some of which were available as the children of survivors."

Genzer — with a resilience that likely is admired by all — moves forward with his life.

His mother, Jamie, a member of the internationally known Sweet Adelines women's chorus, would sing to her two children every morning to wake them for school rather than setting an alarm.

Her son, now 40, still heeds the advice she gave on the last morning of her life, when she softly sang to him and his sister for the last time.

Never forgetting the words, he sings softly in his office, and lives by its final message.

"Good morning to you!... We're all in our places ... with bright shiny faces. This is the way to start our new day!"

Dealing with grief

Is it too late to tell someone you're sorry about their loss?

"It's never too late," Fischer said.

There's no timeline on grief, regardless of the cause of death. However, deaths that are sudden and unexpected present complex grief issues, Loved ones often died alone, there was no time to say goodbye, and it was unexpected, she said.

She stresses not to avoid talking to someone just because you don't know what to say.

"You don't have to say much. Just be there with them," she said. "But don't quiz family members about the details of the death, unless they want to tell you. And refrain from giving suggestions on how they 'should' cope."

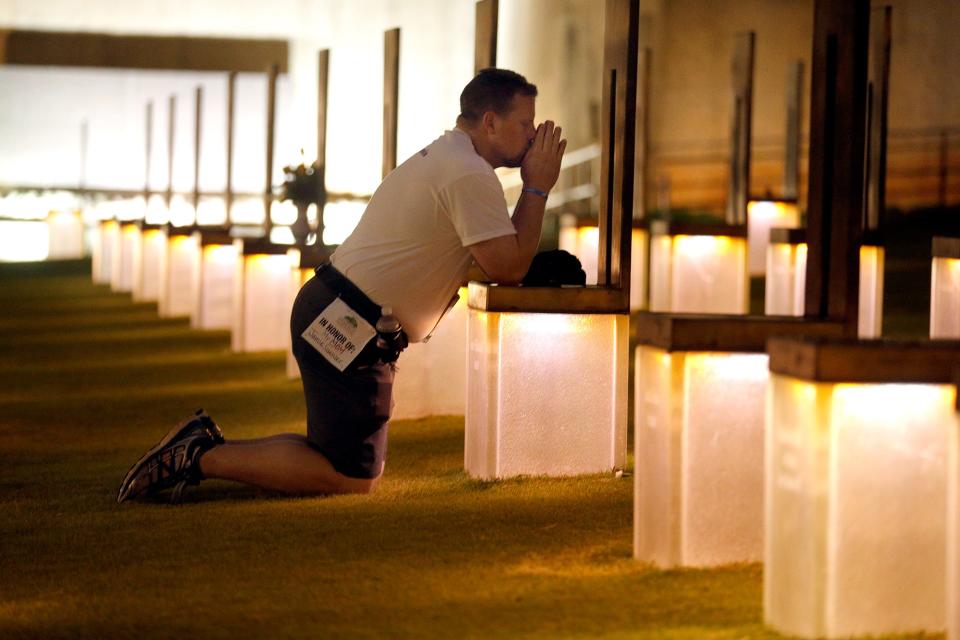

The Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum — with nearly 120,000 items collected from the fence and the 168 chairs since the bombing — has emerged as one way people find a catharsis, not just for the families who lost loved ones, but for those who live here.

"The storytelling means that the people who are mourning not only share their grief but also shape meaning in the community," said OU assistant professor, Dr. Darcie DeAngelo, a medical anthropologist who has conducted public health research at Harvard Medical School. "What values do we share? How do we know who is good?"

More personal than many museums, Oklahoma City's memorial is unique because it focuses on the victims killed rather than the perpetrator of the crime, and DeAngelo said the families become the spokespersons for these narratives.

A shadow box in the foyer of Genzer's home contains an earring and the watch Jamie Genzer was wearing when she died. The items helped identify her after the blast.

The shadow boxes aren't the only tributes to his late mother, though.

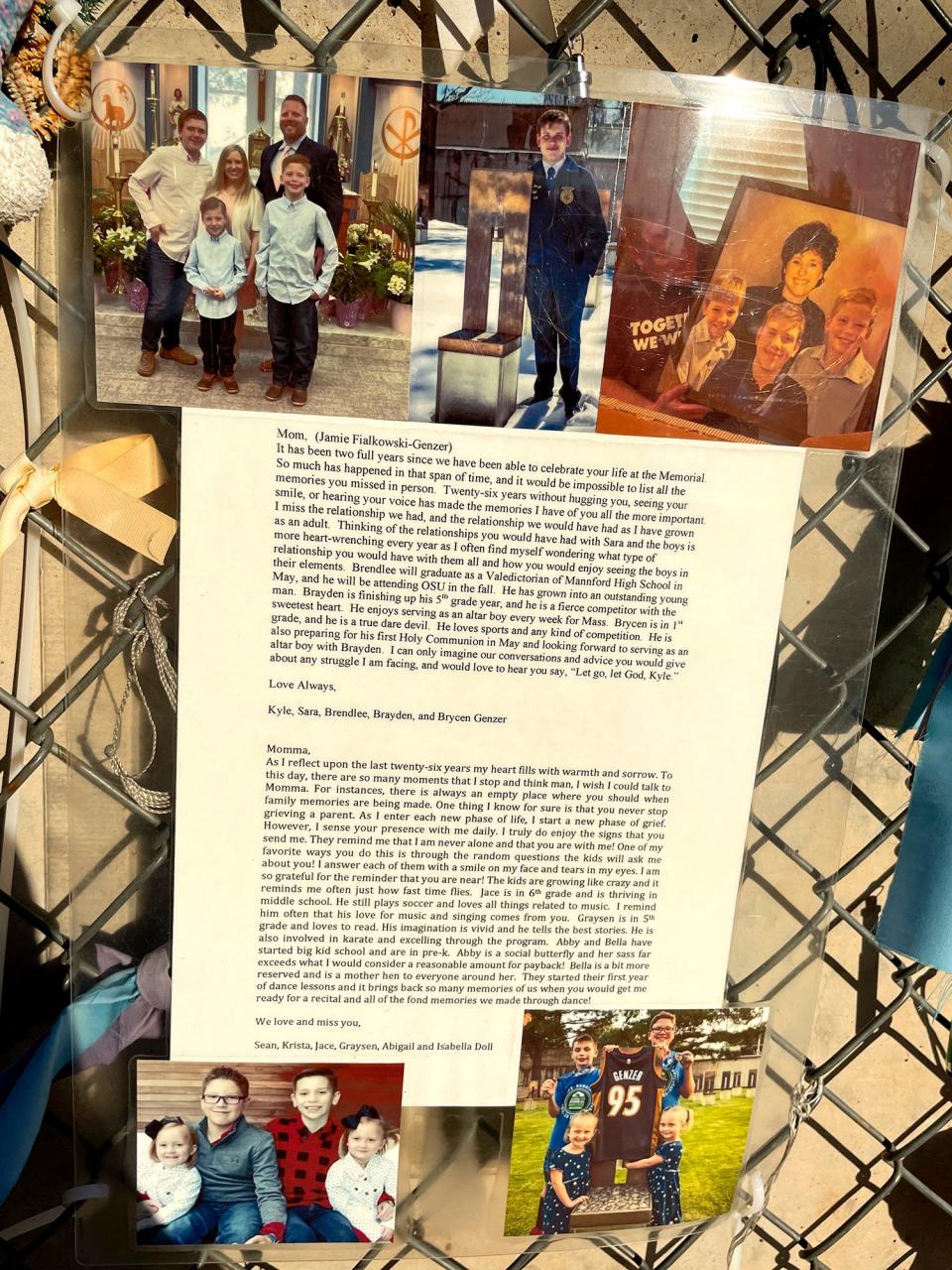

Led by his sister, Krista Doll, both have written love or "life" letters to their mother, complete with family updates and photos nearly every year for the past 13 years or so. Three of the laminated letters — much like a holiday newsletter — remain firmly attached to the fence at the Oklahoma City memorial.

"It's priceless ... allowing us to leave things up (on the fence). It allows us to keep telling our story," he said.

However, not everyone wants to post a photo or teddy bear. Others may not want to speak of the bombing again. And that's OK, too, Fischer said.

Kari Watkins, the museum's executive director, said she doesn't think Oklahomans "grieve differently than others, although faith plays a larger role than it might in other communities."

"I do think that Oklahoma City has shown the world that in memorializing ... the contemporary way of 'memorializing' is leaving something of yourself behind (at the fence). Everyone remembers differently. This is how people stop to do it," she said.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Families of OKC bombing victims find ways to grow through their grief