Controversial law punishing doctors who spread COVID misinformation on track to be undone

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Tucked into a state Senate bill revising aspects of the Medical Board of California is a brief but unambiguous clause undoing a controversial law that was intended to curb “dissemination of misinformation or disinformation related to COVID-19.”

If the bill passes as expected this week, it will put an end to the saga of Assembly Bill 2098, a well-intentioned, poorly worded and ultimately doomed effort to curb the most flagrant cases of COVID-related falsehoods by people wielding medical licenses.

“We are happy that the Legislature is attempting to address the defects in last year’s legislation,” said Chessie Thacher, a senior attorney with the ACLU of Northern California, which filed amicus briefs in four separate lawsuits related to AB 2098. “As we argued in court, that bill was dangerously overbroad and confusing.”

AB 2098 applied to conversations between patients and their doctors about the patient’s care.

“When someone blatantly provides misinformation, totally inaccurate information — especially with intention — that harms patients,” then-Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), a pediatrician and co-author of the measure, said in October. “That takes away the patient’s ability to make appropriate decisions.”

Read more: Doctors fear California law aimed at COVID-19 misinformation could do more harm than good

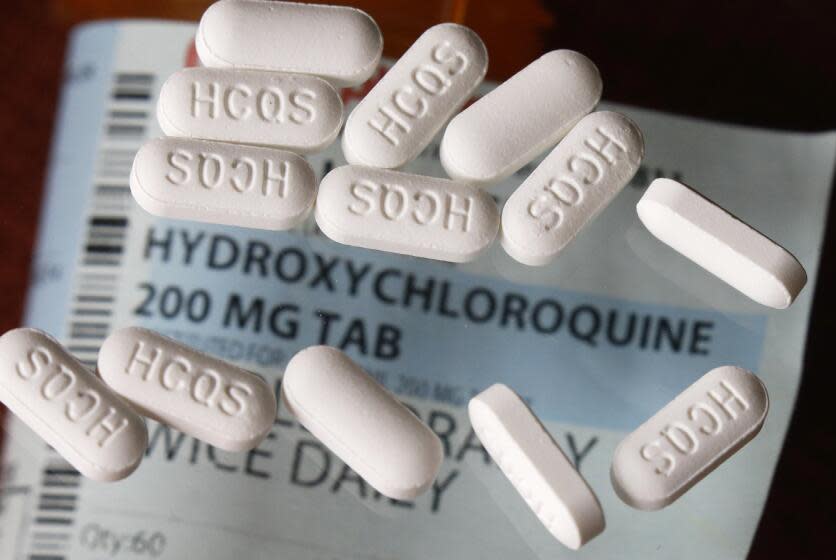

The bill was written with extreme examples of irresponsible rhetoric in mind, Pan said at the time, such as that of Dr. Simone Gold, the Beverly Hills physician who founded the anti-vaccine group America’s Frontline Doctors and promoted debunked COVID-19 treatments. (Gold’s medical license was suspended last year after she pleaded guilty to unlawfully entering the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. It has since been restored.)

But the final text did not apply to any fringe claims aired in public forums such as social media or the Capitol steps. Such provisions would probably not survive a 1st Amendment challenge in court, a legislative analysis of the bill found.

It was endorsed by the California Medical Assn., which represents nearly 50,000 physicians throughout the state.

Gov. Gavin Newsom expressed some unease about the bill’s wording in his September 2022 signing statement, writing that he was “concerned about the chilling effect” of legislating doctor-patient conversations.

However, he was satisfied the law was “narrowly tailored to apply only to those egregious instances in which a licensee is acting with malicious intent or clearly deviating from the required standard of care.”

Read more: Law aimed at doctors who spread COVID-19 misinformation is put on hold by judge

Other readers pointed out that the text of the measure contained no clear definition of such egregious instances, and contained passages immune to clear interpretation.

In granting a preliminary injunction in January in two related cases that challenged the law’s constitutionality, Judge William Shubb of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California ruled that the law’s “unclear phrasing and structure” could have a “chilling effect.”

The final text defined misinformation as “false information that is contradicted by contemporary scientific consensus contrary to the standard of care.”

“Put simply, this provision is grammatically incoherent,” Shubb wrote. “It is impossible to parse the sentence and understand the relationship between the two clauses.”

The bill’s vague wording gave critics from all corners room to stretch it to fit their purposes.

Misinformation purveyor and Democratic presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy Jr. seized on AB 2098, bringing suit against the bill and hailing Shubb’s ruling as a “Huge win ... in this battle for freedom.”

Read more: California lawmakers pass reforms to doctor discipline cases, giving patients a voice

Even staunch opponents of medical misinformation found the bill a flawed weapon in the fight against falsehoods. California law already bars doctors from lying to their patients or dispensing shoddy medical advice that fails to meet the standard of care for all diseases, including COVID-19, they noted.

“We do not need an extra bill in this state to regulate medical practice,” said Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease specialist at UC San Francisco and director of the UCSF-Bay Area Center for AIDS Research, or CFAR. “I think it is prudent to repeal this bill.”

Assemblyman Evan Low (D-Campbell), one of the bill’s original authors, also seemed unbothered by AB 2098’s looming disappearance from state code.

“Fortunately, with this update, the Medical Board of California will continue to maintain the authority to hold medical licensees accountable for deviating from the standard of care and misinforming their patients about COVID-19 treatments,” Low said in a statement.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.