Convict in decades-old Ocean County mob hit claims teeth hold the key to his freedom

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

TOMS RIVER A reputed soldier in the Lucchese crime family, in prison for decades on charges related to the 1984 golf-club beating death of a Toms River used car salesman, now claims he was at the dentist when the killing occurred, but only recently learned his dental records were secretly altered to destroy his alibi.

In a case rich with mob turncoats and crime families warring for control over boardwalk video poker machines, 72-year-old Martin Taccetta of Florham Park continues to claim he was framed by overzealous prosecutors for crimes he didn't commit related to the murder of Toms River auto dealer Vincent "Jimmy Sinatra'' Craparotta.

That is despite trial testimony from former Mafia underbosses that Taccetta told them he and an associate "whacked'' the victim "over some Joker Pokers'' and chose golf clubs rather than baseball bats to do the job because "bats break.''

Taccetta's contention that prosecutors framed him by eliciting perjured testimony from mob informants is nothing new. His attempts to get a new trial on those grounds have repeatedly failed in the decades since his conviction.

But now, Taccetta also claims the assistant attorney general who prosecuted him in 1993 hid from him an FBI report that concluded his dental records - which he says proved he was at his dentist's office an hour away when Craparotta was killed - were secretly altered to destroy his alibi.

Taccetta claims he learned of the FBI report in recent years through a Freedom of Information Act request, and he maintains that the potentially exculpatory evidence forms grounds for a new trial.

A hearing on his motion for a new trial is scheduled for Nov. 1 before Superior Court Judge Dina M. Vicari in Ocean County.

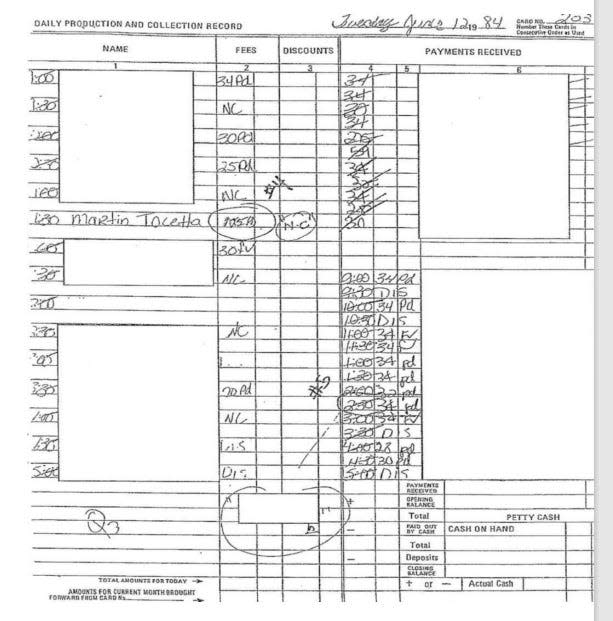

Craparotta, 56, was beaten to death by men with golf clubs at his Route 9 car lot on June 12, 1984, reportedly to scare his nephews into paying tributes to the Lucchese crime family from earnings on their video poker machines.

Craparotta in 1983 was identified by state police as a loanshark and bookmaker associated with the Lucchese crime family. His nephews, Pasquale "Pat'' and Vincent Storino, had amassed an amusement empire along the Point Pleasant Beach boardwalk and, with a third individual identified as an associate of the Bruno-Scarfo crime family, owned a company that made video poker machines.

Taccetta and two other reputed members of the Lucchese crime family were charged with Craparotta's murder. They stood trial in Superior Court in Ocean County in 1993, along with two other alleged mob associates charged with racketeering and extortion offenses.

Co-defendant Michael Ryan was acquitted of the murder, as was Taccetta, but the jury found Taccetta guilty of racketeering, conspiracy and extortion.

Toms River resident Thomas Ricciardi, described as a high-ranking enforcer for the Lucchese crime family, was the only one of the three charged with Craparotta's murder to be convicted of it.

Despite that, Taccetta received the harshest penalty of all the defendants - life plus 10 years in prison with no chance for release on parole before 30 years.

Ricciardi turned government informant days after the verdict and was released from prison into witness protection in 2001, a year before his earliest parole eligibility date.

Taccetta remains in prison.

At the trial, the state relied on "uncorroborated testimony'' of two government cooperators "who were trying to testify their way out of more than 10 murders and myriad other crimes committed by each,'' Taccetta's attorneys, Marco Laracca and Steven Duke, a former Yale University Law School professor, said in their motion for a new trial.

The government witnesses who implicated Taccetta in Craparotta's murder were Philip Leonetti, former underboss of the Philadelphia-based Bruno-Scarfo crime family, and Alphonse D'Arco, former underboss of the New York-based Lucchese crime family, whom the defense attorneys refer to as "cooperating serial killers.''

Leonetti, at the trial, testified about meetings between members of the two crime families in an ongoing dispute over which family would control the Storinos' video poker machine business and derive extortion payments from it.

Leonetti told the jury that during those meetings, Taccetta and Ricciardi both admitted killing Craparotta, according to the defense motion. Leonetti testified Taccetta explained they chose golf clubs over baseball bats to commit the murder "because bats break,'' the defense motion said.

D'Arco testified Taccetta told him, "both he and Ricciardi had 'a lot of heat' on them because 'we whacked this guy, Craparotta. We whacked him ...over some Joker Pokers with a golf club. We knocked his head in,'" the defense motion said.

Taccetta's lawyers now claim that suppressed evidence revealing Taccetta was at his dentist's office when Craparotta was killed shows those two witnesses were lying, not only about the murder for which the the defendant was acquitted, but about the state's entire case.

"Any evidence that defendant did not participate in the murder virtually destroys the credibility of Leonetti and D'Arco, who were the foundation of the state's entire case,'' the defense motion said.

"They both quoted defendant as saying he was a participant in the murder,'' it said. "If he was at the dentist's an hour's drive away when Craporatta was killed, however, he was very unlikely to have later claimed to be one of Craporatta's killers. He was also unlikely to have said that the murder was to help get control of Storino's joker pokers. If Leonetti and D'Arco lied about who killed Craporatta and why, they lied about an essential element of the prosecution's entire case, not merely about whether defendant was guilty of murder.''

The state, in a reply brief, takes a different position.

"Even if defendant were not present at the murder, though all evidence indicates he was, he still could have bragged about it to Leonetti and D'Arco, so it would not have affected the witnesses' credibility as to the other charges against defendant,'' Jaclyn R. Dowd, deputy attorney general, wrote in the response brief.

If the state did withhold an FBI report about Taccetta's dental records from the defense during the trial, "that non-disclosure was at most harmless error, and therefore should not impugn on the validity of defendant's convictions for extortion, racketeering and conspiracy,'' she wrote.

The defense attorneys in their motion say Taccetta was at his dentist's office, more than an hour's drive from the murder scene, at 11:30 a.m. on June 12, 1984. The murder occurred around 10:30 a.m. that day, the motion said.

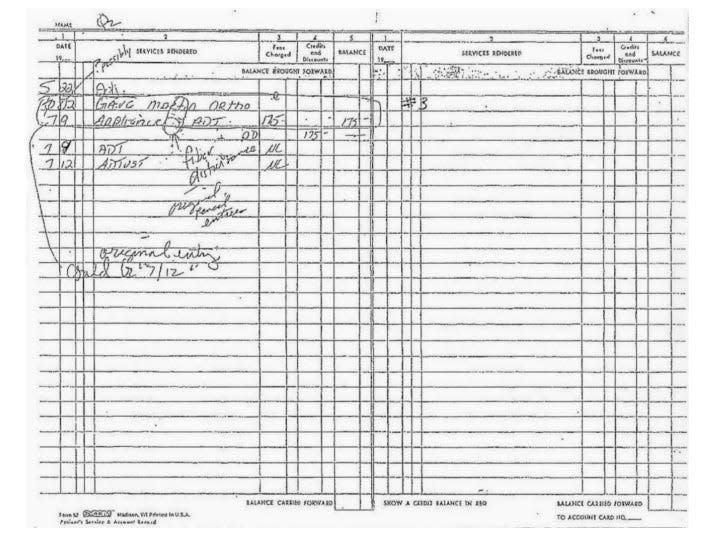

"His attorney gave informal notice of an intent to prove an alibi but discovered that the dentist's records had been altered to obscure the original record that defendant had been at the dentist at that time and place and had paid $175 for the procedure,'' the motion said. "It was therefore impossible to mount a credible alibi defense, and defendant did not pursue it.''

Taccetta's dentist did not have an independent recollection of the date and time of the dental appointment without referring to the records, said Duke, one of the attorneys now representing Taccetta.

Taccetta and his codefendants weren't charged in the Craparotta case until April 1991, almost seven years after the murder.

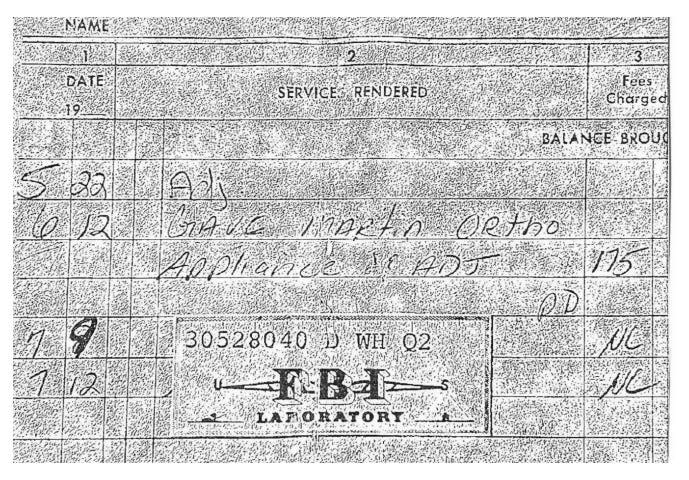

At the time of the trial, the defense was unaware that Special Assistant Attorney General Robert Carroll, who was in charge of the prosecution, sent a copy of Taccetta's dental records to the FBI in Washington, D.C. to analyze them and determine if and how they had been altered, the defense motion said.

Carroll relayed Taccetta's claim that he was at the dentist on the day of the murder and expressed concern that the date and time of the dental appointment "may have been tampered with,'' Laracca and Duke wrote in the defense motion.

"He expressed the hope that the FBI lab's analysis would not only prove that the records relating to that date had been tampered with, but that it would provide evidence on that subject that would incriminate the defendant,'' the motion said.

Carroll sent the records to the FBI less than a week before testimony in the trial was set to begin, it said.

Carroll's investigators traveled to Washington, D.C. 15 days later to obtain the results of the FBI's analysis, it said. That was six days after the results became available and eight days after the start of the trial, the motion said.

"Among those results was the photographic removal of writing over the original record, beneath which clearly emerged an entry recording that defendant received a dental appliance in the office for which he paid $175 on June 12, 1984, the day of the murder,'' the motion said.

The records sent to the FBI for analysis had an entry that said "Gave Martin Ortho,'' the motion said.

"The visible date for 'Gave Martin ortho' is 8/12, although it appears that the month on the original entry was obliterated, and 8 was substituted,'' it said.

That entry was followed by an entry in July, so the entry of an 8 for August above it "appears to have been an awkward attempt to disguise the true date of 6/12,'' the motion said.

"This was confirmed by the FBI who uncovered the obliteration and found a 6 underneath it, thus restoring the original record that the device was delivered on 6/12,'' the motion said.

"Immediately underneath the 8/12 entry was a 7/9 entry, apparently inserted to suggest that the appliance was obtained on that date,'' it said. "The FBI determined that that first 7/9 was not on the original but had been added by the tamperers.''

The dental records indicated some fees were generated by an 11:30 appointment for Martin Taccetta, but the amount of the fees was obliterated, the motion said. The FBI produced a blowup of the entry revealing "NC'' written over 175, it said.

Taccetta's attorneys claim in their motion that the prosecutor's suppression of the FBI analysis of the altered dental records "was a blatant violation'' of the 1963 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brady vs. Maryland, which requires prosecutors to turn over potentially exculpatory evidence to the defense.

The FBI's restoration of the original records "supported the defendant's alibi, and the alteration of those records was a criminal obstruction of justice,'' the motion said.

"An evidentiary hearing might reveal whether it was a member of the prosecution team who defaced the dentist's records,'' the motion said.

"The defendant had no motive to deface the dentist's records,'' it said. "No one other than state or federal law enforcers had a motive to destroy the defendant's alibi defense.''

The defense attorneys suggest in their motion that Taccetta and the others were charged in the case in retribution for the embarrassment caused to law enforcers when, in 1986, he and 19 other purported members of the Lucchese crime family were acquitted of all counts in a 21-month federal trial on drug, gambling and other charges.

Dowd, in the state's reply brief, said there is no basis for the defendant's claim that the state sought to keep the FBI's report about Taccetta's dental records from him, or that the records were defaced by an investigator.

"It is just as, if not more, likely that the dental office may have made the markings,'' the state's reply brief said.

Throughout the dental records "are many similar cross-outs, circles and other notations,'' likely made by the dentist's staff, and other unreadable portions not related to Taccetta's defense, the reply brief said.

Most notably, the top of one page "clearly reads 'Tuesday, June 12, 1984,'" the brief said.

"If someone defaced the dental records solely to prevent defendant from mounting his alibi defense, it is entirely unclear why this date would be left untouched,'' the state's brief said.

"The state submits that there is no basis for the defendant's claim that any federal or state agent tampered with and/or suppressed these records,'' it said.

"Additionally, ...the dental records would not have provided a complete defense, as the appointment was after the time of the murder and, therefore, defendant could have gone to the dentist afterward, especially given the fact that Ricciardi is the one who actually committed the beating that ended the victim's life,'' Dowd wrote in the reply brief.

"It is, of course, possible that (Taccetta) could have participated in the Craparotta murder and then rushed to his dentist's office an hour away and sat quietly in the dentist's chair while a device was installed in his mouth,'' the defendant's attorneys wrote in response to the state's reply brief. "But that is not an argument that the state wanted to have to make to the jury. Altering the records rendered that somewhat farfetched argument unnecessary.''

Neither the state's brief or the defendant's motion stated where the office of Taccetta's dentist was located.

Taccetta's attorneys also contend in their motion that prosecutors knew shortly after the trial that Ricciardi and Taccetta were innocent and that Leonetti and D'Arco offered perjured testimony at the trial. That information came after Ricciardi and another defendant, Anthony Accetturo, began cooperating with the state, the motion said.

Less than three weeks after the verdict in the Craparotta case, Ricciardi pleaded guilty in federal court to racketeering and conspiring to murder nine named individuals, Craparotta not among them.

In 1995, he also pleaded guilty in state court to conspiring to murder nine individuals, including Craparotta.

Ricciardi told fellow inmates in protective custody at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York that he and Taccetta had been falsely accused of Craparotta's murder, the defense motion said.

A number of inmates submitted affidavits swearing to that, among them Salvatore "Sammy the Bull'' Gravano, former underboss of the Gambino crime family.

Gravano, whose testimony put Gambino crime boss John Gotti behind bars, advised Ricciardi to "quit complaining and get with the program,'' and told him, "You are part of Team America now,'' Taccetta's motion says.

"It doesn't make any difference whether you killed nine people or 10, as long as you tell the truth,'' Gravano swore he told Ricciardi, according to the motion.

Dowd said in the state's brief that Taccetta's claims of perjured testimony were previously considered by lower court and appellate judges and found to be without merit, and do not now warrant reconsideration.

With his perjury claims discounted, Taccetta in 2005 went forward with a hearing on a claim that he received bad advice from his trial attorney, David Ruhnke, and turned down a plea bargain as a result, only to be found guilty by the jury.

Subpoenaed to appear at the hearing in Ocean County, Ricciardi - by then Taccetta's bitter enemy - briefly came out of witness protection and testified that Taccetta turned down the plea bargain because he was confident he would be acquitted of all the charges

Asked by Duke at that contentious hearing whether he had told Taccetta not to worry about mob informants because they were liars, Ricciardi responded, "I have never met a guilty gangster in my whole life."

Superior Court Judge James N. Citta in 2005 granted Taccetta a new trial on the basis of ineffective assistance of counsel and ordered him released from jail.

The state Supreme Court reversed Citta's decision in 2009, reinstated Taccetta's conviction and ordered the defendant back to state prison.

The Asbury Park Press reached Taccetta by telephone before authorities showed up at his home that day to return him to prison.

"I'm innocent of these charges, and they want to put me back for life,'' he told the Press.

"I know this is organized crime, but what about the Constitution?'' he said.

Taccetta remains housed at East Jersey State Prison in Woodbridge. His earliest parole date is Feb. 5, 2027.

Kathleen Hopkins, a reporter in New Jersey since 1985, covers crime, court cases, legal issues and just about every major murder trial to hit Monmouth and Ocean counties. Contact her at khopkins@app.com.

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: Convict in 1984 Ocean County mob hit says teeth will set him free