Convicted child killer faces death penalty once again in Broward. Is it the last time?

Decades after a convicted child molester killed two girls in Broward, a jury is deciding if he should live or die — for the third time — following recent changes to the death penalty.

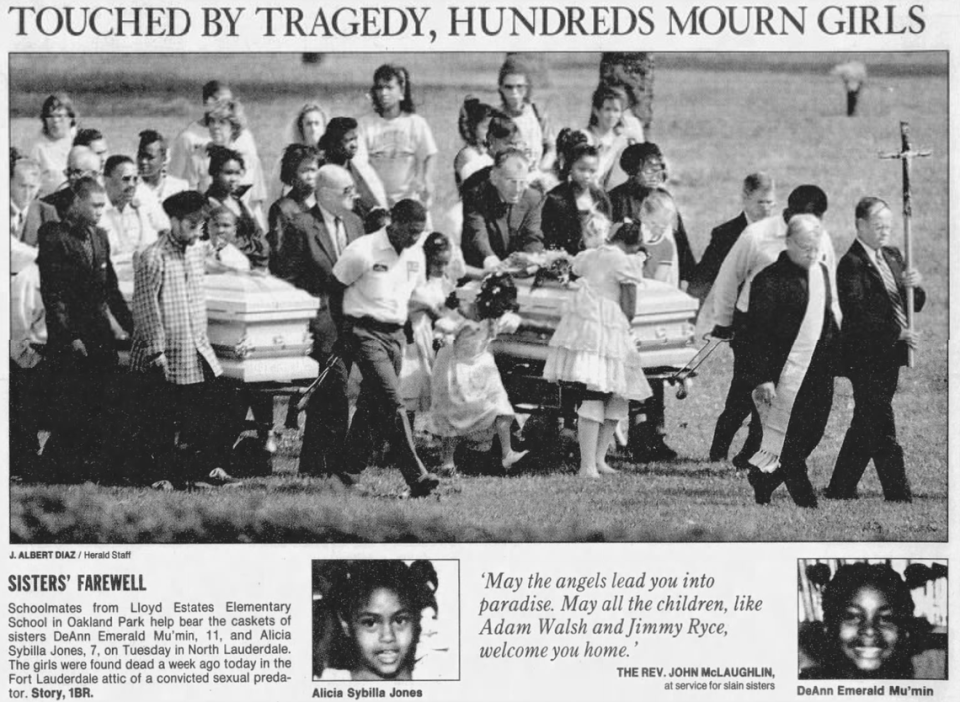

In 1999, Howard Steven Ault was convicted of raping an 11-year-old girl in front of her 7-year-old sister before strangling both girls and shoving their bodies in his attic. The 57-year-old is currently sitting through a resentencing for the 1996 murders of DeAnn Emerald Mu’min, 11, and Alicia Sybilla Jones, 7, whom he lured into his Fort Lauderdale duplex with the promise of Halloween candy.

Facing the possibility of being condemned to death row a third time, Ault’s fate depends on eight jurors after Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a law last April that allows juries to recommend a death sentence with an 8-4 vote instead of a unanimous vote. Florida now has the lowest threshold in the U.S.

DeSantis pushed for the change in law after the Parkland school shooter, who killed 17 in 2018, was spared from the death penalty. In late 2022, only nine of the 12 jurors voted for death.

READ MORE: DeSantis signs death penalty bill. It could have sent Parkland shooter to death row.

The latest changes the death penalty has undergone raises uncertainty about its future in Florida, said Craig Trocino, director of the Innocence Clinic at the University of Miami’s School of Law.

Resentenced for a third time?

In 2017, the Florida Supreme Court granted Ault, who was on death row, a new sentencing hearing after it found that Florida’s death penalty process was unconstitutional because it didn’t require that jurors make a unanimous decision.

The jury in the 2007 resentencing recommended Ault be put to death in a 9-3 and 10-2 vote for the murders of DeAnn and Alicia, respectively.

READ MORE: Convicted child killer sought to fire attorneys before third death penalty sentencing

Jurors in the original sentencing, which took place in 2000, opted to send Ault to the electric chair. But three years later, the Florida Supreme Court ordered a new sentencing over concerns about the jury selection process at Ault’s trial.

The order for Ault’s 2017 resentencing was brought on by the U.S. Supreme Court finding Florida’s sentencing scheme unconstitutional, Trocino said. And looking back at the case’s outcome may shed some light on what could be in store in the future.

U.S. Supreme Court weighs in

In the Hurst v. Florida case, the Supreme Court justices ruled that all jurors must find aggravating factors, or facts related to a crime, before handing down a death sentence. The court also found that Florida judges had too much power compared to juries in death penalty cases.

After the ruling from the nation’s highest court, Florida’s Supreme Court found the law unconstitutional and declared that death sentences must be determined by an unanimous jury instead of in a 10-2 vote.

“That raises the very real possibility that the United States Supreme Court can find that scheme unconstitutional, and we’re back to where we are now with Mr. Ault and many similarly situated people,” Trocino said.

Before Hurst v. Florida, Trocino said, a jury could have agreed on an aggravating circumstance — that the crime was heinous, atrocious and cruel or cold, calculated and premeditated — but it wasn’t known how many jurors voted for which factor.

Under current state law, a jury must unanimously find that prosecutors proved at least one aggravating factor beyond a reasonable doubt. They must also determine that aggravators outweigh mitigating factors, which provide context related to the defendant that could be used to help advocate against the death penalty.

Following the Hurst decision, the state had to determine which death row inmates would be eligible for resentencing, Trocino said. They did so by considering another case in which the U.S. Supreme Court weighed on the death penalty: Ring v. Arizona.

The court ordered that anyone on death row who was sentenced before the Ring decision in 2002 wouldn’t receive a resentencing. Though convicted in the ‘90s, Ault qualified under the criteria because of his second death penalty sentencing in 2007.

Death penalty cases, like Ault’s, can take decades from verdict to sentence. Resentencings can be costly, time consuming and emotional exhausting for a victim’s loved ones.

However, for Trocino, they’re also traumatic for the jury.

“I don’t think that’s discussed nearly enough,” Trocino said. “...The jury is sitting there listening to all of this, having to assess all of this, and then [they have to] vote on this ultimate sanction or not.”