He was convicted of killing their dad. Now a Florida family is fighting to clear his name.

For decades, Patti Kreusler Ceravolo has been haunted by her father’s 1976 murder, never believing that the right man was convicted and fearing the real killer was still on the loose.

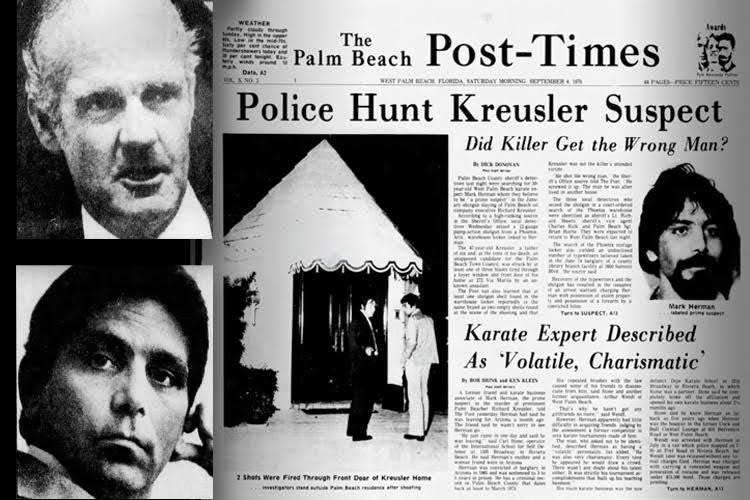

Enlisting the help of three of her five siblings, she amassed thousands of records that convinced her family that Mark Herman, a Florida karate instructor, shouldn’t have been found guilty of killing her father, Richard, a politically connected Palm Beach oil executive.

The three sisters have compiled charts, written reports and scoured the internet and the country for information, hoping to find out who and why someone wanted their father dead.

Now, nearly 50 years later, they believe they are closing in on the man who opened fire when the 47-year-old Kreusler answered the door of his home just north of the Palm Beach Country Club, a brazen and inexplicable slaying that gripped the community.

But even with that elusive prize within reach, the Kreuslers have put their investigation on the back burner.

Instead, they are focusing their attention on Herman, hoping to persuade authorities to officially exonerate him before it’s too late.

“Mr. Herman is 76 years old. We want to get him his pardon,” said Kathleen Kelly, a retired architect who joined her sister’s quest. “It destroyed his life, and we’re desperately trying to find someone to help us with this process.”

Two years ago, all six siblings took the unusual step of writing to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Cabinet, supporting Herman’s request to have his murder record wiped clean.

While they knew they would face strong headwinds, they were hopeful the voices of the victim’s children would carry weight with the state’s top officials, who serve as the Board of Executive Clemency.

Instead, without addressing the Kreuslers’ letter, DeSantis this year dashed their hopes.

Without any fanfare or even an official announcement, DeSantis quietly decided not to hear clemency requests from anyone convicted of murder, attempted murder or felony sex crimes.

“Accordingly, the governor has denied your request for clemency and your application has been closed," according to a form letter that arrived in Herman's mailbox in May. He was advised he can reapply in two years.

With that door slammed shut, the Kreuslers turned to Palm Beach County State Attorney Dave Aronberg, who two years ago created a Conviction Review Unit. Calling wrongful convictions “contrary to our mission in this office,” he promised to investigate claims from those who have exhausted their appeals but still maintain their innocence.

In 1992, Gov. Lawton Chiles and the Cabinet unanimously agreed to commute Herman’s life sentence. After serving 15 years in prison, he was set free.

But the Kreuslers insist that the 1992 decision didn’t go far enough. By law, Herman is still a convicted murderer, and they want that damning and unwarranted label removed before it’s too late.

“We owe it to him. We owe it to his family,” Ceravolo said. “His legacy is not what they said he was. He is not a murderer.”

Palm Beach murder case was Palm Beach County's first live televised trial

The decision to commute Herman’s sentence was the culmination of decades of startling turns that punctuated the most notorious murders in the county’s history — one that snared national attention.

From the moment of his 1977 arrest, Herman insisted he had nothing to do with the shooting death of the influential businessman, who had just returned home from a reception for Democratic Gov. Reuben Askew, was working on Republican President Gerald Ford’s re-election campaign, went fishing with sugar baron Alfonso Fanjul and was about to join the Palm Beach Town Council.

At his arraignment on a charge of first-degree murder, Herman carried a hand-lettered sign: "I Am Being Framed. Perjury, Politics, Forgery." While he had a long criminal record for assault, drug sales, burglary and assault, he insisted murder wasn’t in his wheelhouse.

Despite his claims of innocence, Herman was convicted in 1978 after a nine-day trial that was the first in the county to be televised live and riveted residents from Boca Raton to Jupiter.

The evidence against Herman in the Jan. 16, 1976, fatal shooting was circumstantial. No weapon was found. Kreusler, who died 13 days after the shooting, never identified his killer. No one saw the shooter flee from the house after firing three bullets, one of which lodged in Kreusler’s stomach.

Instead, the prosecution team, led by then Assistant State Attorney Jack Scarola, relied primarily on testimony from four convicted felons, who claimed Herman confessed to the shooting when they shared a cellblock at the county jail.

They testified that Herman said he shot Kreusler by mistake. His real target was Billy Glocker, who was staying at his parents' house next door to the Kreuslers, they said.

Enraged that Glocker ripped him off in a drug deal, Herman decided to settle the score. Hopped up on morphine and Dilaudid, Herman went to the wrong house.

Dexter Coffin III, a Palm Beach heir to the flow-through teabag fortune who was awaiting trial on charges that he sold a $115,000 yacht he didn’t own, claimed Herman sent him a letter, confessing to Kreusler’s murder. Coffin read from it during the trial.

Later, Coffin told a Palm Beach Post reporter that he, not Herman, wrote the letter. Two of the others recanted their testimony in interviews with celebrity journalist Geraldo Rivera for the nationally televised show “20/20” on an episode titled, “A Killer in Camelot.”

The fourth inmate, who carried a Bible to the witness stand when he testified that Herman confessed to him, was a self-proclaimed mob hitman who was convicted of murders in Palm Beach and Broward counties and later Nevada. After the others recanted, he told a Post reporter he was sticking by his trial testimony because he hoped to use it to bargain for his freedom.

The inmates’ claims were also disputed by Glocker. He told Rivera that he never purchased drugs from Herman, contradicting the inmates’ and ultimately the prosecution’s claims that Herman wanted him dead.

Long before the inmates admitted they lied, the judge who presided over Herman’s trial said he had concerns about their testimony, which he described as “critical.”

Rejecting a death sentence sought by prosecutors, Circuit Judge Thomas Sholts noted that the inmates testified in hopes of winning reduced sentences for their own crimes. He described one as a “well-known manipulator” and another as an “admitted perjurer.”

“This court cannot send the defendant to his death based at least partly upon the testimony of such persons," Sholts wrote, when he sentenced Herman to life without the possibility of parole for 25 years.

Ceravalo, who watched the trial from her hospital room after giving birth to her first child, said she never bought the prosecution theory that her father’s death was a case of mistaken identity.

“It sounded ludicrous to me,” she said. “I never thought Herman did it. I was the black sheep of the family.”

But, her sisters said, they, too, doubted that Herman shot their father by accident.

Kreusler-Walsh said she and her mother, who died in 2012, initially tried to investigate what happened. But they uncovered little information.

It was a scary time, she said. Her mother didn’t want to speak out publicly, fearing those involved might return and hurt her family.

“She was petrified to go out and get the newspaper,” Kreusler said of her mother, who ultimately sold the Palm Beach house, seeking security in a gated North Palm Beach community.

For a time, Kelly said she, her mother and other family members thought Herman might have been working with others. But, they said, over the years, it became clear Herman wasn’t involved.

“By the time she passed she absolutely believed he didn’t have anything to do with it,” Ceravalo said.

'A punk . . . but no killer': Prosecution's case against Mark Herman unravels

The admissions from Coffin and others that they lied and Glocker’s claims that he didn’t know Herman were just the beginning of large holes that were ultimately blown through the prosecution’s case.

Faced with a public records lawsuit, then-State Attorney David Bludworth in 1985 finally released the results of an investigation he ordered a year after Herman’s conviction. Concerned about growing claims that Herman was wrongfully convicted, Bludworth ordered Assistant State Attorney Joel Weissman to review the case.

Weissman, who left the prosecutor’s office in 1979 and was then in private practice, told reporters he concluded that Herman was innocent. In the report, he said Herman and a man named John Crotty may have been accomplices.

But Weissman said he didn’t believe that Herman was involved. He said he mentioned Herman’s name in the report only because he had been convicted of Kreusler’s murder.

"Herman might be what we call a punk. … But he's no killer,” said Weissman, who is now one of the county’s leading divorce attorneys.

By the time the report was released, Crotty had long since disappeared. There is no evidence Bludworth pursued him.

In the years after Herman’s conviction, his defense attorney was also discredited. Alfonso Sepe, who didn’t call a single witness to testify in Herman’s defense, went on to become a Miami-Dade Circuit Court judge.

In 1993, he was arrested as part of Operation Court Broom, a sweeping investigation into corruption on the bench. Acquitted by a jury, he ultimately pleaded guilty to accepting $150,000 in bribes to fix cases.

Kreusler-Walsh said it wasn’t one thing that finally convinced her that Herman wasn’t responsible for her father’s murder. It was the sheer quantity of information that came to light.

“I’m a recent convert,” she admitted. “But I feel sorry for him. I never thought I’d say that.”

Their youngest siblings, who were living at home at the time of their father’s murder, were latecomers, too. Unlike their older sisters, who were away at school, the two youngest were at home when gunfire erupted and a third returned home shortly afterward.

“The younger kids suffered more,” Kelly said. “It is still emotional, especially for the youngest ones — very emotional.”

Still, after reading the information their sisters gathered, they, too, agreed that Herman deserves a pardon.

Richard Kreusler's family believes his murder 'had to do with business'

The family’s investigation occurred in stops and starts over the years.

“We’d bring it up, it would become emotional, and we’d have to put it away or we’d hit a dead end and put it away,” said Kelly.

Bill Hagler, a private investigator who had long believed his friend was innocent, finally got in touch with them and shared the information he had.

The advent of the internet helped immensely, Ceravolo said. It gave her easy access to newspaper clippings not just about her father’s murder and Herman’s trial but about the political climate at the time of her father’s murder.

“It was the Wild West,” she said.

Ceravolo and Kelly tried to keep their emotions from influencing their investigation. They referred to their father only by his initials, RGK.

During the trial, there was talk that Kreusler was having an affair with a stripper and his murder may have been connected to that indiscretion.

“We knew we could find things we didn’t want to find out,” Kelly said. “So we made it impersonal.”

The murder came as the nation was reeling from a gas crisis that was began with the 1973 Arab oil embargo and was fueled by continuing unrest in the Middle East. Competition among oil distributors was fierce, according to a report that Kelly and Ceravolo prepared.

Kreusler, whose company Richard Oil Corp. sold gas to Amoco service stations and operated retail stations, was in the thick of it. He served as a spokesperson for an association of gasoline dealers. He advised the County Commission on rationing, their plans to raise gas taxes and how to use tax receipts to figure out how much gas was sold in the county.

At the same time, organized crime had infiltrated the gasoline business and its tentacles reached South Florida.

During their research, the sisters learned about a strange meeting their father had with two men just days before he was murdered. At the conclusion of the meeting, an office worker overheard Kreusler telling the two men “not to do business with the son-of-a-bitch or he wouldn’t do business with them.”

After he was shot at his front door, Kreusler said: “The son of a bitch got me," The Post reported.

Ceravolo and Kelly were reluctant to talk about all of their findings, saying they want attention focused on Herman and his pardon. But, they said, the reasons for their father’s murder were obvious if police had properly investigated at the time.

“Investigators never ever looked at his business,” Kelly said. “We were like, 'Are you joking?'”

They said they hoped Aronberg’s investigators would use the information they gathered and, using subpoena power of the office, finally find their father’s killer.

“We truly believe it had to do with business,” Ceravolo said.

If they are wrong, they said they wish someone at the State Attorney’s Office or the clemency board would tell them why they continue to believe Herman is guilty.

“What do you know that we don’t know?” Ceravolo said. “We haven’t found one thing to tie him to this. Not one thing.”

Mark Herman pins exoneration hopes to clemency request

Herman, who has spent the past 30 years of his life in Phoenix, said he is happy to have the Kreusler family’s support. But, he said, he has been disappointed so many times, he doesn’t get his hopes up.

His appeals to overturn his conviction were rejected by more than 20 different state and federal judges before an Orlando lawyer he never met filed papers seeking clemency for him.

Six years after attorney Sharon Stedman filed the petition, Chiles and the Cabinet voted unanimously to commute Herman’s sentence.

After reviewing court records and Herman’s spotless prison file, Chiles said he had “serious concerns” about Herman’s guilt. But he and the Cabinet stopped short of giving him a pardon.

Quoting a letter Sholts wrote on Herman’s behalf, Chiles said that “showing mercy by granting this petition will not impugn the jury verdict nor impair the administration of justice.”

Herman said Chiles told him he could apply for a pardon if he stayed out of trouble for a year. But, he said, he had his mind on other things.

“It was such a fight to get clemency,” he said during a telephone conversation from his home in Arizona. “I wasn’t in that mode at all. I was just enjoying life, spending time with my family. I was free.”

Further, he said, Stedman had represented him for free. “I didn’t feel right asking someone to spend further time on me,” he said.

It wasn’t until two years ago, at the urging of Hagler, the support of the Kreuslers and the help of Stedman, that he decided to try again.

But instead of filing a straight-forward petition, outlining the facts, Stedman wrote a blistering letter. She aimed particular venom at Scarola, who left the state attorney’s office decades ago and is one of the county’s leading civil litigators.

Kreusler-Walsh said she was appalled when she learned what Stedman had written. “I didn’t want her to take that tack,” she said. “It was a diatribe. It was a rant. It was awful,” she said.

Scarola responded by writing a letter to the clemency board, describing Stedman’s claims that Herman was the victim of a wide-ranging conspiracy as “fantasies.”

“The crusade to challenge that conviction is at best misguided and at worst a platform for personal publicity,” he concluded.

By turning Scarola into an enemy, Stedman’s letter hurt, rather than helped, Herman’s hope for a pardon, Kreusler-Walsh said. Stedman has since retired and is no longer eligible to practice law in Florida. She didn’t return a phone call for comment.

Shortly after he applied for the pardon, Herman said he learned Aronberg had started the Conviction Review Unit and decided to try that route as well.

Steve Shepherd, five-time world kickboxing champion who was friends with both Herman and Aronberg, agreed to help, Hagler said. Shepherd, who trained at Herman’s karate studio decades ago, died in May 2021.

“When Steve died, communication with the state attorney died with him,” Hagler said.

But, the Kreusler family said, they will keep pushing.

“We’re just trying to find out what happened,” Ceravolo said. “He didn’t do this. I don’t care if he was a badass and made some bad decisions. He isn’t a murderer.”

Jane Musgrave covers federal and civil courts and occasionally ventures into criminal trials in state court. Contact her at jmusgrave@pbpost.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: A Florida family's clemency bid for dad's convicted killer Mark Herman