Cops broke Heat fan’s eye socket after 2013 title game. He’s still waiting for justice.

His blood no longer stains the sidewalk, but Francois Alexandre can still point to the spot where police slammed him to the ground, beat him and broke his eye socket outside his apartment in downtown Miami.

It was June 2013, and the Miami Heat had just won their second straight NBA championship. Alexandre, then a 27-year-old college student, was celebrating with other fans a few blocks from AmericanAirlines Arena on Northeast Second Street when police forced them off the street. Alexandre complied, he said, by moving to the sidewalk.

But police kept pushing forward, yelling “Move!” as they held up their bicycles.

Alexandre started recording with his cellphone. He told police he was a taxpayer and that he knew his rights. He told the crowd they didn’t have to leave. Then without telling him he was under arrest, a lieutenant placed Alexandre in a “headlock around the neck” and pushed him against the wall, judges later concluded. Five other officers then drove him into the ground. Some beat him, officers admitted.

Much has changed since that summer night. The lieutenant is now a captain. LeBron James left Miami. But Alexandre, now 34, is still waiting for justice. He filed a civil lawsuit against those involved in 2016. Two of the officers involved in his arrest are scheduled to go to trial in January, facing allegations of excessive force and battery.

His is one of multiple cases of police violence in Miami that have been put back under the spotlight amid a national reckoning over police brutality brought about by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis by police there.

Standing on that same sidewalk seven years later, Alexandre cried. He then balled up a fist and pointed it to the sky.

Weeks of protests have given him confidence that the public is behind him in his fight. He is no longer a victim, he said, but a “revolutionary.”

“It’s not even better late than never,” he told the Herald. “It’s that the time is now.”

Take-down caught on camera

Just after 1:30 a.m., after Heat fans spilled onto the streets to celebrate the championship, a bicycle squad from Miami Police responded to the corner of Biscayne Boulevard and Northeast Second Street, where a small crowd had gathered.

A police report of the incident says that the police had responded to a report of people trying to overturn cars. Alexandre, who joined the crowd as he walked back to his apartment at Vizcayne Towers on Second Street, said that claim was never substantiated.

The bike squad was led by the since-promoted Lt. Javier Ortiz, the former president of the Miami police union who has in the past defended police accused of killing unarmed Black men — and even children, including 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland.

Ortiz, now a captain, has also been the subject of legal and formal complaints about his use of force on the job, including a 2013 lawsuit alleging that Ortiz beat a man over a glow stick at Ultra Music Festival. In January, Ortiz was suspended for telling Miami’s only Black city commissioner that he, too, is a Black man, despite being of Hispanic origin. He was the only officer who claimed to have seen anyone attempt to overturn a car in the area the night Alexandre was injured, judges later concluded.

Earlier that night, after the Heat beat the San Antonio Spurs to claim their second consecutive NBA title, fans blocked traffic on Biscayne Boulevard and some climbed traffic signs. As the group gathered near Alexandre’s apartment, police formed a line and slowly moved toward the crowd, pushing them west. Alexandre, who was born in Haiti and raised in Plantation, said he sensed that the police profiled the group because most of its members were Black.

In his gut, he said he felt like the police were pushing them toward Overtown, the historically Black neighborhood where they may have believed they belonged, he said. Most nights, however, he laid his head above theirs, on the 33rd floor at the luxury high rise overlooking the arena and the Freedom Tower.

That night, he wouldn’t sleep at all.

He cussed at the officers and told those in the crowd they didn’t have to listen to the orders. Then one of the officers appeared to push over a woman in the group, her body rolling to a stop at Alexandre’s feet. He grew louder and pointed the camera directly at Ortiz, whom he accused of the shove.

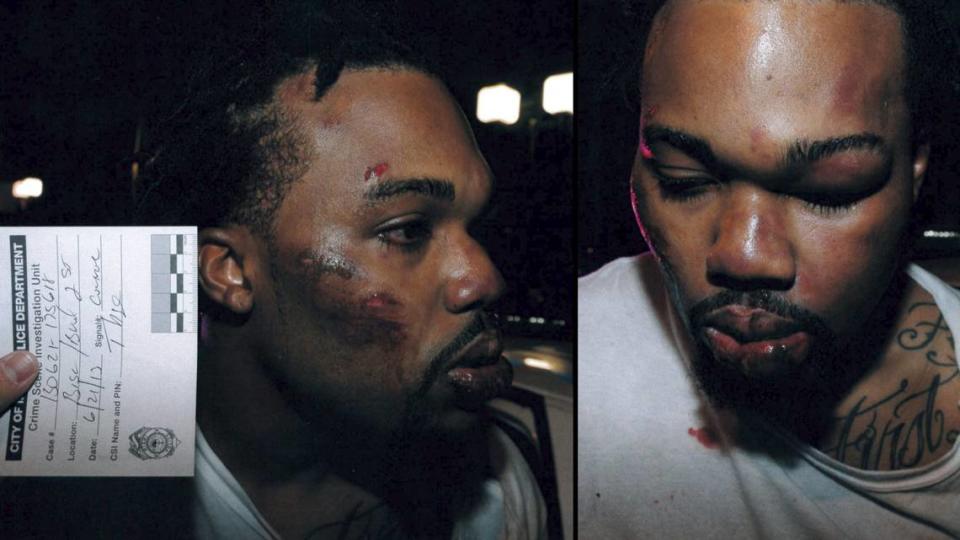

That’s when — according to photographs from the scene, surveillance footage and video from Alexandre’s phone — Ortiz grabbed Alexandre around the neck and shoved him into an alcove near the Vizcayne apartment complex. More officers helped slam him to the ground, where at least five then piled on top of him and pummeled him into submission.

All the while, he yelled that he was not resisting. They told him to “shut the f--- up.”

There was “no reasonable need” for the police to throw Alexandre down and “strike, kick or smother him,” U.S. District Judge Darrin Gayles wrote in a 2018 order mandating that Ortiz and two officers — Josue Herrera and Magdiel Perez — stand trial in civil court for violating Alexandre’s Fourth Amendment rights by exerting unnecessary force and state law by committing battery against him.

“The battery was severe enough to fracture [Alexandre’s] orbital bone and to cause facial lacerations and bruising,” Gayles wrote. “The [officers’] use of force, on a non-violent man for what amounts to a misdemeanor, simply is not proportional to the need for that force.”

After standing him up, police walked Alexandre to a squad car, where Alexandre said he would remain handcuffed for multiple hours before being taken to Jackson Memorial Hospital and later to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, where his orbital fracture was reviewed.

One of his arresting officers can be heard on a hot mic from Alexandre’s still-recording phone mocking him for his bloodied lip.

“You have lipstick on you, sir, now you need heels,” the officer said.

Police later accused him of inciting a riot and resisting arrest, charges that were later dropped. Of the six officers named in Alexandre’s lawsuit, only two — Herrera and Perez — will stand trial in January after a combination of legal loopholes and logistical problems whittled down the list of defendants.

Ortiz, who led the take-down, won an appeal in 2019 after U.S. Appeals Court judges in the Eleventh Circuit determined that the trial judge erred in not granting Ortiz so-called “qualified immunity,” an infamous legal protection for public officials that shields police from civil lawsuits unless they can be proven to have violated “clearly established” constitutional rights.

Alexandre said his rough arrest was more than a beat down. It was an attempt to silence him.

“I decided to speak up,” he said. “They assumed that I was a threat and they neutralized the threat, according to their words. But they beat me up. This was the first time I ever got arrested.”

Face of a movement

At the time, Alexandre was less concerned about his injuries than about graduating from Florida International University. He was worried that the arrest would disqualify his enrollment.

“I didn’t care about what happened to my face, what happened to my eye,” he said. “I just cared about finishing college. I cared about making sure that I can get up in society.”

Alexandre blamed himself for what happened and fell into a depression, finding lessons in the melancholic music he listened to, like Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror.”

As his injuries healed, and the passage of time eased his trauma, he tried to move on with his life. He graduated with a degree in international relations, formed a social service organization called Konscious Kontractors Inc. and became a father.

At the time of Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis, Alexandre was in full coronavirus-response mode, organizing food distributions in Little Haiti.

The video of Floyd’s death, under the weight of the knee of a white police officer, rattled him and brought back the pain of what happened to him. After protesting the killings of Michael Brown in St. Louis and Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Alexandre felt compelled to protest his beating by Miami Police. So he created a petition and printed posters displaying his gruesome injuries and a haunting message: “Do I have to die before I matter?”

“I could be on my soap box and get upset as to why somebody didn’t support me yesterday [or years ago] but the time is now to ignite everybody to be on the same page to talk about justice,” Alexandre said. “Not just for me but for everybody else that’s on that platform.”

Whether it be marching in Little Haiti or South Beach, Alexandre said he has felt energized by the weeks of protests organized in Miami against police brutality. He has lent his voice to the broader cause, catalyzed by the high-profile killings of unarmed black men and women in the U.S., while younger activists have shared their spotlight with him.

“What’s really striking for me that would even bring me to tears is how good I feel, how good I feel being out there with them,” Alexandre said. “And knowing that this change is not something that’s going to break or something that’s just going to stop. This feels genuine.”

While his lawsuit has advanced irrespective of the Floyd case, Alexandre said the changing tides of public opinion mean more people like him will get the recognition their cases merit in real time — not seven years later.

“It sucks that George Floyd had to die for my case to be resurrected, but the only thing we can do now is leave a legacy that George Floyd would be in solidarity with,” he said. “That means peeling back all the layers of oppression to start anew. The only way you can do that is to amend some of these wrongs.”

Jonnie Gartrelle, the 31-year-old leader of some of Miami’s recent protests, said by shining a light on local cases of police brutality demonstrators can pressure government leaders to do more than condemn racism as a concept or tweet support for the families of a slain individual once every few years.

“Cases like Francois’ are something that happens every day in the Black community,” Gartrelle said. “You have to put the pressure on [government] and that’s why this localization is important. Now is the time to hammer them and set a precedent.”

Alexandre’s lawyer, Leonard Fenn, said that Miami Mayor Francis Suarez and Police Chief Jorge Colina — who have spoken out against Floyd’s killing — should review the footage of his client’s violent arrest and reassess their future press statements.

“The chief of police and the mayor are now voicing words to the extent that this is going to stop and we’re no longer going to have bad cops,” Fenn said. “They should put their money where their mouth is.”

Alexandre seeks monetary damages for his “pain and suffering, his prior medical and legal expenses and his emotional distress,” Fenn said. If the case goes to trial, assuming the city’s attorneys do drop out of the case, Fenn said he will seek attorney’s fees and costs as well as “punitive damage.”

Even if Alexandre wins the case, the officers will again be able to appeal and seek qualified immunity.

“The defense in these cases is well aware of the uneven playing field set up by the doctrine of qualified immunity and use it to dictate unfair settlements,” Fenn said in a statement. “Francois refused to be bullied and settle. Francois’s case is a textbook example of the unfair delays and advantages for the police baked into the system. As has often been said justice delayed is justice denied. Francois is still seeking justice.”