Stop pinning your hopes on coronavirus antibodies: 3 major issues mean they're no silver bullet

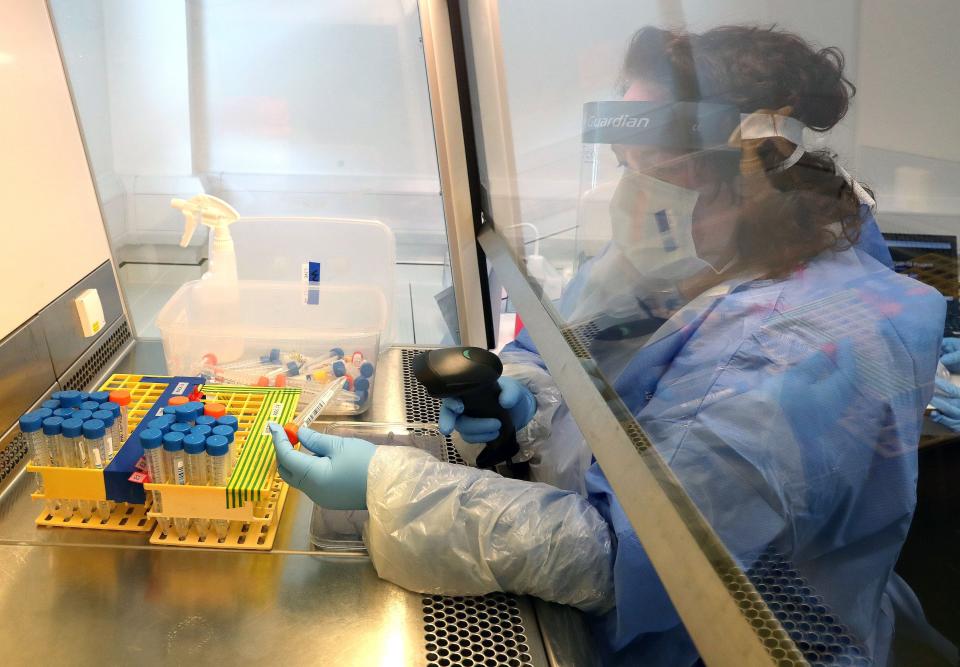

Many companies are developing tests meant to identify people who have recovered from COVID-19 by detecting coronavirus antibodies in their blood.

The presence of antibodies probably means someone is immune for at least some amount of time and could return to work safely, which is why some experts see antibody tests as crucial to helping countries restart their economies.

But there are lingering doubts about whether all coronavirus infections generate antibodies and how long the protection lasts.

Plus, antibody tests can be inaccurate, and many people are taking tests that lack authorization from the Food and Drug Administration.

We all want to return to a life without the specter of COVID-19.

It's what the protesters in Colorado, Wisconsin, and Michigan have demanded in their push to reopen nonessential businesses. It's the goal politicians and public-health experts have in mind when developing road maps to help states forge a safe path back to some level of normality.

But such plans require far more testing than the US is now doing, even after a recent ramp-up. Experts also still want a more accurate sense of how many Americans have been infected already.

For those seeking answers, antibody testing offers a tempting promise: Such tests are meant to identify whether a person already had COVID-19 — even if they never showed symptoms — and therefore is likely to have immunity.

At least 140 US biotech companies are racing to develop these tests; seven have gotten emergency-use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration, as has a test at New York's Mount Sinai Hospital.

Jens Meyer/AP

"Ultimately, this might help us figure out who can get the country back to normal," Florian Krammer, a virologist at Mount Sinai's Icahn School of Medicine, told Reuters in March. "People who are immune could be the first people to go back to normal life and start everything up again."

But "ultimately" is a long way off. As of now, we still lack several critical pieces of information about antibodies and immunity. Scientists don't know whether everyone who has recovered from COVID-19 develops antibodies, and they don't know the extent to which those antibodies protect us from reinfection.

"We expect people that are infected with COVID-19 to develop a response that has some level of protection — what we don't know right now is how strong that protection is, and if that's seen in everybody that is infected, and for how long that lasts," Maria Van Kerkhove, an expert with the World Health Organization, said at a press briefing on Monday.

Plus, antibody tests aren't always accurate.

Does everyone who gets the coronavirus develop antibodies?

Coronavirus antibody tests, also known as serological tests, use a few drops of your blood to determine whether your body has developed proteins that fight the virus. If it has, that means you've gotten infected, recovered, and may be immune. These tests differ from the diagnostic tests that determine whether someone has an active COVID-19 infection.

Omar Marques/Getty Images

Research so far indicates most patients develop antibodies: A small study from European researchers found that three coronavirus patients had antibodies less than three weeks after being infected. A March study in the journal Nature reported, similarly, that patients formed antibodies within weeks.

But a recent paper found that of 175 recovered COVID-19 patients in China, 6% didn't develop any detectable antibodies. About 70% of those studied developed high levels of antibodies about 10 to 15 days after the disease's onset, while a quarter of the patients developed low levels of the neutralizing proteins. The study has yet to be peer-reviewed, however.

We don't know how long antibodies confer immunity

Generally, once your body has antibodies to fight off a particular disease, you can't get it again. But some types of antibodies weaken over time.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has said it's unlikely that people would get the coronavirus more than once — at least within a short time period.

"If this virus acts like every other virus that we know, once you get infected, get better, clear the virus, then you'll have immunity that will protect you against reinfection," Fauci recently told the "Daily Show" host Trevor Noah.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

But scientists still aren't sure how long coronavirus antibodies last, since the virus has not been around for enough time to study long-term effects. Previous research on SARS, a closely related coronavirus, found that antibodies disappeared after two years.

Some reports have already described people who appear to have recovered and then tested positive for the coronavirus again later. This was the case for a Japanese tour guide who got sick, got better, and then tested positive three weeks later. Doctors aren't sure whether she was reinfected or had not fully recovered from the first infection.

The South Korean CDC also recently reported that 51 patients who recovered from the coronavirus tested negative and then positive again within a relatively short time.

Some tests don't accurately sniff out antibodies

Even assuming patients do develop antibodies that confer immunity, we don't yet have many foolproof ways to detect them.

In the US, the FDA has granted emergency-use authorization to eight antibody tests. The agency reviews data from the test manufacturers when considering these EUAs, but the green light is still "less rigorous than securing FDA approval for a new diagnostic test," FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn told Politico.

There are also plenty of tests that do not have any FDA approval. That's because the agency announced on March 16 that to afford test developers "flexibility," companies could begin distributing antibody test kits without authorization or any scientific review by the agency. Those companies are simply required to validate their own tests, warn anyone who takes them, and notify the FDA.

"The FDA does not review the validation, or accuracy, data for these tests unless an EUA is submitted," the agency said in a statement.

Hundreds of those unapproved tests have since flooded the market.

Andrew Milligan/AFP/Getty Images

But of course, tests that have not been vetted can yield unreliable information. Last week, two teams of California-based scientists reported the results of antibody surveys in Santa Clara County and Los Angeles County. The findings suggested that the number of infected people in the counties could be up to 85 times and 55 times the number of confirmed cases. But it turned out that the antibody tests those surveys used were not FDA-approved and had a false-positive rate nearly equal to the percentage of participants they found to have antibodies.

"Literally every single one could be a false positive," Marm Kilpatrick, a disease ecologist from the University of California at Santa Cruz, told BuzzFeed News. "No one thinks all of them were, but the problem is we can't actually exclude the possibility."

The concept of 'immunity passports'

Ray Chavez/MediaNews Group/The Mercury News/Getty Images

Even if antibody tests were perfectly accurate, and all recovered patients were confirmed to have antibodies that confer immunity, it may still be unrealistic to think recovered people would then kick-start our economy anytime soon.

Several countries, including Germany and Chile, are considering issuing "immunity passports" to recovered patients that would exempt them from lockdowns and social distancing. Fauci told CNN on April 7 that there could be "merit" to the idea of immunity certificates in the US.

"This is something that's being discussed," he said.

Mike Segar/Reuters

But WHO experts have discouraged governments from issuing this type of "immunity" certification. At this point in the pandemic, the organization said, there is not enough evidence to indicate that recovered patients develop antibodies that guarantee protection from reinfection.

"The use of such certificates may therefore increase the risks of continued transmission," the organization said in a scientific brief.

What's more, WHO estimates that no more than 2% to 3% of the global population has developed coronavirus antibodies.

An economy can't bounce back with just 2% to 3% of its workforce. Schools can't reopen with that small a sliver of teachers or students. So while accurate, robust, widespread antibody testing is needed, it's no silver bullet.

Holly Secon and Blake Dodge contributed reporting to this story.

Read the original article on Business Insider