Coronavirus antibodies remain in the blood for almost two months, study shows

Up to one in 12 people who have had coronavirus will not develop antibodies – but people who do still have them two months later, research suggests.

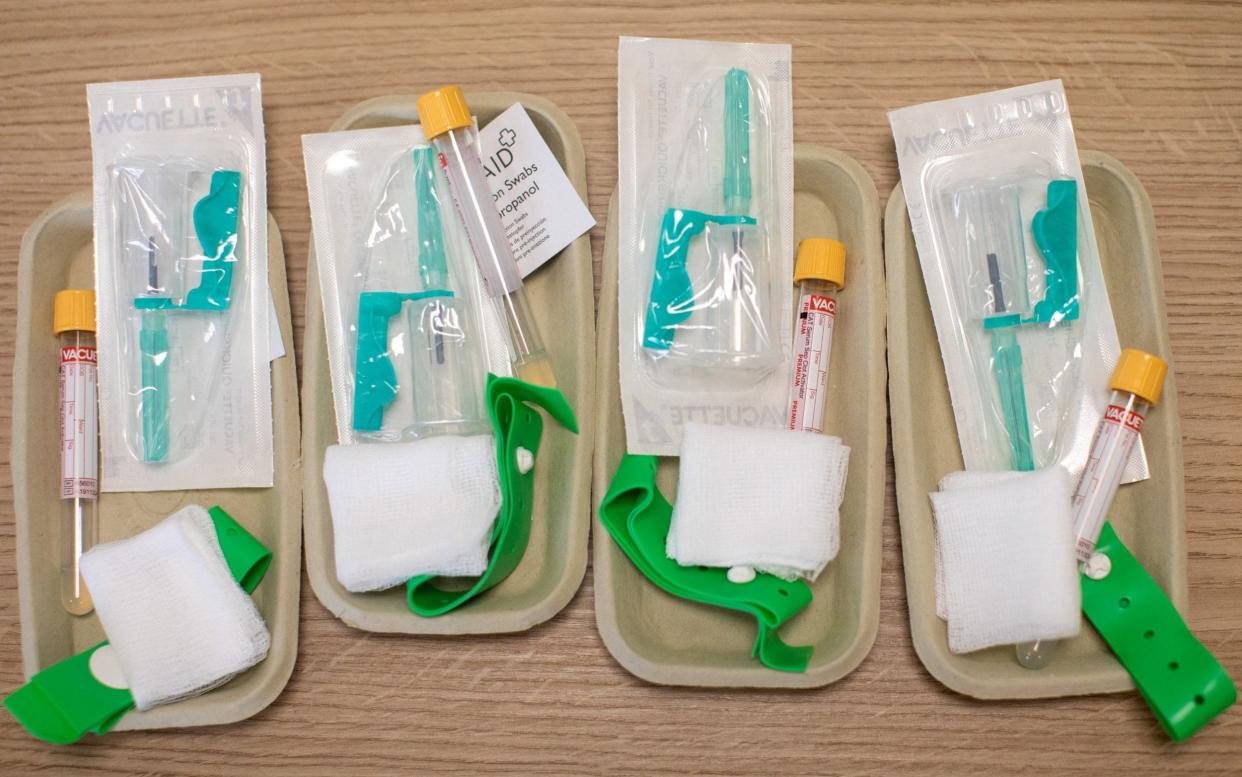

The NHS has begun rolling out antibody tests, which it is hoped will show who has previously had the virus and whether they have become immune to it.

However, scientists are unclear about the degree of protection and how long it lasts, meaning it has not so far been possible to develop "immunity certificates" showing who is protected.

The new study shows that Covid-19 antibodies remain stable in the blood of the majority of infected people for almost two months after diagnosis – and possibly longer – but it also found antibodies were not detectable in everyone exposed to the virus.

In the study, between two per cent and 8.5 per cent of patients did not develop Covid-19 antibodies at all.

Researchers said this could be because the immune response in these patients could have come through other immune response mechanisms, such as different antigens or T-cells. Alternatively, relatively mild infections may be restricted to particular locations in the body that are not picked up in antibody responses.

The study was led by researchers and clinicians at St George's, University of London and St George's University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust in collaboration with the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Mologic Ltd and the Institut Pasteur de Dakar, Senegal. It analysed antibody test results from 177 individuals who had previously been diagnosed with Covid-19.

The pre-print study, which has not been peer-reviewed, measured the levels of antibodies in patients exposed to coronavirus. It found that, in those patients with an antibody response, the levels remained stable for the duration of the study – almost two months.

Patients with the most severe infections with the largest inflammatory response were more likely to develop antibodies.

This may be due to antibody responses working in parallel with an inflammatory response to severe disease, or that a higher viral load could lead to greater stimulation of the inflammatory and antibody development pathways, researchers said.

Sampling by the Office for National Statistics suggests that at least 70 per cent of coronavirus sufferers are asymptomatic, and the new findings suggest such cases are less likely to develop an immune response.

Professor Sanjeev Krishna, corresponding author on the paper from St George's, University of London, said: "Our results provide an improved understanding of how best to use viral and antibody tests for coronavirus, especially when not every person exposed to the virus will have a positive response.

"We need to understand how best to interpret the results from these tests to control the spread of the virus, as well as identifying those who may be immune to the disease.

"With the number of infections in the UK going down, we now have the very welcome challenge of attempting to carry out more tests to understand whether other factors are associated with an immune response, such as viral load and genetic factors.

"We hope that, by sharing our data at an early stage, this will accelerate progress towards effective use of test results around the world."

The study also explored associations between different characteristics and antibody responses.

Being of non-white ethnicity was associated with a higher antibody response, which researchers said was likely to be because non-white ethnic groups were more likely to develop severe disease.

Older patients and those with other conditions, such as hypertension or being overweight, were also more likely to have an antibody response.