As the coronavirus curve flattened, even hard-hit New York had enough ventilators

As American doctors watched their Italian counterparts deny ventilators to senior citizens with coronavirus this year, they clamored for more devices and prepared to live out their greatest fear: denying a dying person the care they need because of a shortage.

But weeks after COVID-19 cases peaked in some of the hardest-hit U.S. states, doctors and administrators who spoke with USA TODAY say they are not aware that doctors turned away anyone for a ventilator. At the worst, some patients shared machines.

“There was a lot of discussion about what would happen if we got to a place like that,” said Michelle Hood, the chief operating officer of the American Hospital Association. “Clinical leadership teams went through the thought process of what would happen. To the best of my knowledge we have not had to make that rationing decision.”

Hospitals did not have to use the triage plans their states drew up to decide who gets ventilators during a shortage. Instead, clinicians used other devices to pump oxygen into gasping patients, to “prevent the vent” as University of Chicago doctors called it.

And, doctors say, the lockdowns and other measures to slow the spread of the virus helped hold down caseloads just enough to make it to the other side of the peak.

“It worked just in time in New Jersey,” said Shereef Elnahal, the CEO of University Hospital in Newark. “Had we (peaked) a week later or two weeks later, we would have seen an overwhelming overload of our healthcare system.

“The curve flattened just early enough for us to not have to make those agonizing decisions,” Elnahal said. “What it shows you, though, is that if we’re not vigilant, for example in the fall, about tracking these cases closely and taking action early … then we could face that easily.”

Now, as public health officials warn about a fall resurgence of the virus, the ventilator supply is getting bigger. A nationwide hospital association is helping hospitals share about 5,000 ventilators. And the federal government has ordered an additional 187,000, with the first batch coming by May 4.

Peaks were earlier and flatter

Hospitals in hard-hit areas needed fewer ventilators than expected, experts say, because social distancing and lockdowns meant that COVID-19 cases peaked earlier and at lower numbers.

The number of new coronavirus cases in New York showed signs of reaching a peak in early April. That’s nearly a month earlier than the early May summit that Gov. Andrew Cuomo had predicted in mid-March.

Elnahal said his New Jersey hospital’s COVID-19 admissions peaked on April 10, earlier than he expected. He said the timeline kept getting earlier every time state officials ran the models. “Over time that date crept up by about a week,” he said.

On April 15, New York sent 100 ventilators to Michigan and 50 to Maryland. The following day, New York sent 100 to New Jersey. That’s a sign that the state has extra – even though Cuomo originally wanted 30,000 and didn’t get nearly that amount.

Medical professionals aren’t faulting Cuomo for asking for so many ventilators because he was planning for the worst-case scenario.

“Responsible leadership at all levels needs to plan for the worst,” Elnahal said.

Sharing a ventilator

The worst situation has been reported in New York, where doctors say a handful of patients had to split ventilators.

Dr. Lewis Kaplan, a Philadelphia-based trauma surgeon and the president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, said he is only personally aware of two New York patients who shared one ventilator.

“The need to put more than one person on a ventilator that was anticipated to be a widespread problem, that hasn’t really surfaced,” Kaplan said. “I don’t know of any place that has said, ‘Sorry we can’t take care of you. You need to go to the palliative care wing.’”

Dr. Scott Braithwaite, a professor at NYU Langone Health, confirmed that splitting happened, but he wouldn’t give specifics.

“I don’t know to what extent that is still continuing,” Braithwaite said, and he said it’s unlikely that doctors or hospital administrators would discuss it publicly.

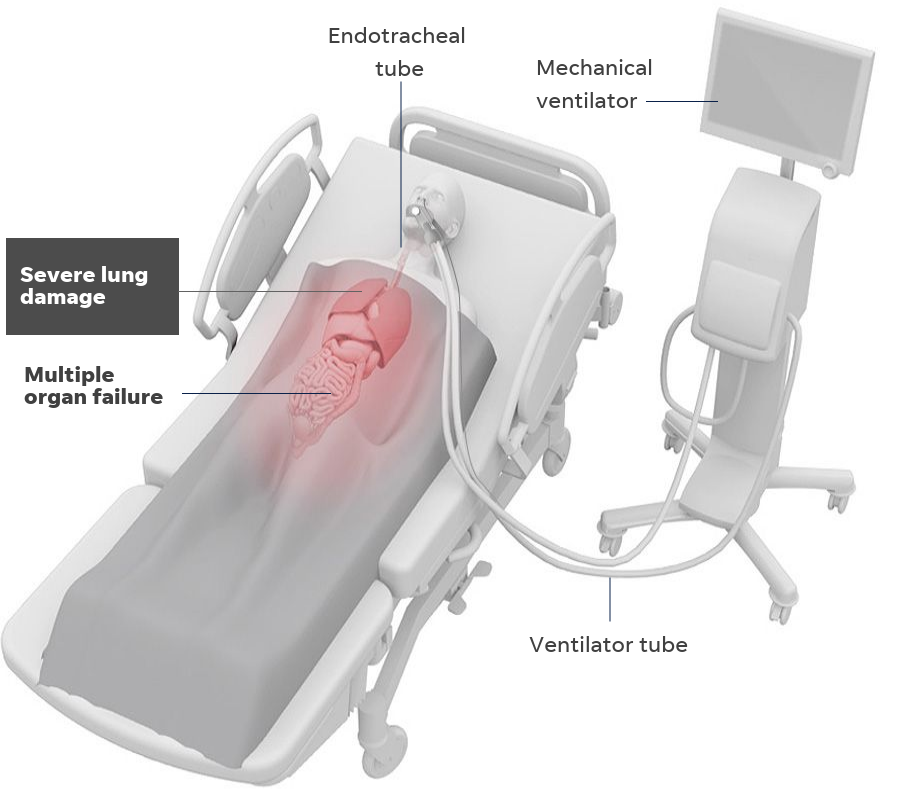

Splitting is a controversial and risky move that involves hooking multiple patients up to the same ventilator. It’s been proven in studies on artificial lungs and animals, but is considered a last resort in humans, used only when the alternative is denying someone a ventilator.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave emergency approval for splitting in anticipation of a ventilator shortage because of COVID-19.

Prisma Health, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, distributed a Y-shaped pipe to split ventilators to 35 states, 94 cities, and 97 agencies. The company said in a statement it is not aware that the device was used to treat patients.

At SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, where one of the hospital’s emergency medicine doctors did the research proving splitting is possible, a spokesman said the hospital never hooked more than one patient to a single ventilator.

Getting creative

Instead of denying ventilators, many doctors changed the settings on anesthesia machines to pump air instead of the sleep-inducing medicine, hooked patients up to sleep apnea devices and cranked up the air pressure, and attached tight-fitting masks to oxygen tubes to keep people alive.

That’s in part because the Society of Critical Care Medicine in March recommended creative use of non-traditional types of ventilators. New York, for example, ordered 3,000 BiPAP machines – traditionally used for sleep apnea – to convert them into ventilators.

“We found innovative ways to meet this need,” Kaplan said. “We found ways to manage things, but it begs the question, ‘Should we not have been far better prepared than what we were?’ and I think the answer to that is unequivocally, ‘Yes.’”

Major U.S. hospitals including Johns Hopkins Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Veterans Administration ordered helmet-style ventilators, according to Advisory Board, a health-care consulting company. The devices surround a patient’s head like a space helmet and provide oxygen.

In the method they call “prevent the vent,” UChicago Medicine doctors pumped oxygen through tubes inserted in 24 patients’ noses and also flipped the patients on their stomachs to help them breathe. Only one patient ended up needing a ventilator, the hospital said in a statement. The procedure spared others any harmful side effects from sticking tubes down their windpipes.

The method is still risky because the oxygen tube can spray the coronavirus around a room as a fine mist. UChicago Medicine said it was able to use this method because it had enough specialized rooms to contain the contamination.

Dr. Lewis Nelson, the head of emergency medicine at University Hospital in Newark, New Jersey, said his hospital wasn’t able to use sleep apnea machines because it didn’t have enough isolation rooms. But the hospital bought more ventilators and borrowed from other places.

“There’s not this excessive supply of ventilators,” Nelson said. “We were able to get enough and share and borrow and repurpose and get from the stockpile. We clearly never ran out, which was great, because that would be quite catastrophic.”

More ventilators are coming

Now that demand for ventilators in New York and New Jersey is on the decline, hospitals in other areas are starting to brace for a surge in the coming days. There’s anxiety, but a better feeling of preparedness.

Hood, at the American Hospital Association, said the Washington, D.C., area, including Maryland and Virginia, have later peak dates. States out west are also expecting later peaks, she said.

Hood said her organization is working with group purchasing organizations, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on a new ventilator reserve that backs up the Strategic National Stockpile.

The federal government sent out about 8,000 ventilators from the stockpile in March and the beginning of April.

Who got help? Rare look at stockpile handouts shows which states got ventilators, masks amid coronavirus

The dynamic ventilator reserve is designed to back up the stockpile. Hospitals and health systems will list their available ventilators in a database and then lend ventilators to one another across the country. Providers in an area with increasing coronavirus cases will be able to tap into the database for help.

The idea is to make sure ventilators don’t sit idle in one place while hospitals in other areas are stretched beyond their ventilator capacity. In total, the inventory has about 5,000 ventilators, Hood said.

“We feel much more confident today than we were two or three weeks ago,” Hood said. “We have been adding to the national emergency stockpile as there’s been purchases made from existing stock both in the U.S. and North America and across the globe.”

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has ordered more than 187,000 ventilators at a cost of about $2.9 billion. The department expects to receive 41,000 by the end of May. The first batch is due May 4.

By that day, all but four states – Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota – will have seen their peak days for ventilator use come and go, according projections as of Monday from a model from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. The model projects that the country will need only 7,228 ventilators on May 4.

Still, Nelson, from Rutgers, said 187,000 is the right amount for the whole country because you can’t have too many ventilators. “We have no idea what we’re going to need, and if it’s easy enough to make them, and it is, I think it’s a good thing,” he said.

Braithwaite, at NYU, said there will still be ventilator demand because the peak doesn’t fall quickly. “It’s not a sharp peak,” Braithwaite said. “It’s more like a gentle hump. So we’re starting to descend on a gentle hump.”

Doctors and public health officials all over the country also are warning about case increases that could come if Americans stop practicing social distancing measures such as working from home and avoiding crowds.

“Now is not the time to relent,” said Kaplan, from the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “You are now starting to see the fruits of your labors but it’s taken this long to see it.

“How many hundreds of thousands of people are positive that we know of?” Kaplan asked. “How many don’t we know of? So, yes, I have concerns. And in this I am not alone.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Coronavirus: Hospitals avoid ventilator shortage as the curve flattens