Coronavirus-killing silver, fake tests, CDC impersonators: Feds rush to stamp out scams

Among all the coronavirus scams that Joan Donovan has been tracking in the last three months, one has stuck with her: an app promising to detect contact with an infected person, but that actually froze the device and demanded a bitcoin ransom.

Donovan, research director of Harvard Kennedy’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, where she tracks disinformation campaigns, has seen her fair share of malware-related scams during her career. Yet this app seemed particularly cruel, given the country’s current widespread isolation.

“If you were to be a person whose lone source of connection in the world right now is through telephone,” she said, to be locked out of that at a time when you can't access support, and that you are feeling really alone, that could be potentially deadly.”

The malicious app is just one of dozens, if not hundreds of scams that have popped up as quickly as the coronavirus itself. Hucksters are hawking bunk cures — toothpaste, silver, essential oils. Fraudsters are shilling counterfeit masks. And most importantly, those coveted coronavirus tests are now available online — except they don’t work.

There is currently no approved cure or vaccine for the coronavirus, and for health authorities trying to contain the coronavirus, which has claimed more than 20,000 lives in the U.S. alone, these scams could lead to even more deaths. One wrong shipment sent to a hospital, one wrong miracle cure that goes viral, could undo weeks of effort to contain the pandemic — a consequence weighing heavily on government officials.

“There’s enough legitimate companies out there that are doing business and producing good high-quality medical equipment,” a senior Department of Homeland Security official told POLITICO. “What we don’t want [is] to send a doctor or a nurse into a situation where they think they’re wearing an N95 [mask], but it’s actually some bootlegged ineffective respirators and now they’re inadvertently exposing themselves.”

Justice Department leaders say they are focusing on efforts to stop coronavirus fraud. In a March 16 memo to U.S. attorneys, Attorney General William Barr wrote that DOJ has seen reports of phishing emails pretending to be from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and of people selling fake cures for Covid-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

“The pandemic is dangerous enough without wrongdoers seeking to profit from public panic and this sort of conduct cannot be tolerated,” Barr wrote, encouraging prosecutors to work with DOJ headquarters on cases related to the pandemic.

And in a memo sent the next week, Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen said the country faces “an unfortunate array of criminal activity” regarding the pandemic, which is “reprehensible and will not be tolerated.”

He listed a variety of reported frauds: robocalls claiming to sell nonexistent respirator masks, social media scams claiming to send people relief checks if they share their bank account numbers, even robberies of people leaving hospitals.

Imported items, meant to go to front-line workers, have also been caught in the hunt for scams. In recent weeks, the Food and Drug Administration, working with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, has found thousands of coronavirus tests and masks that, once inspected, turned out to be bootleg.

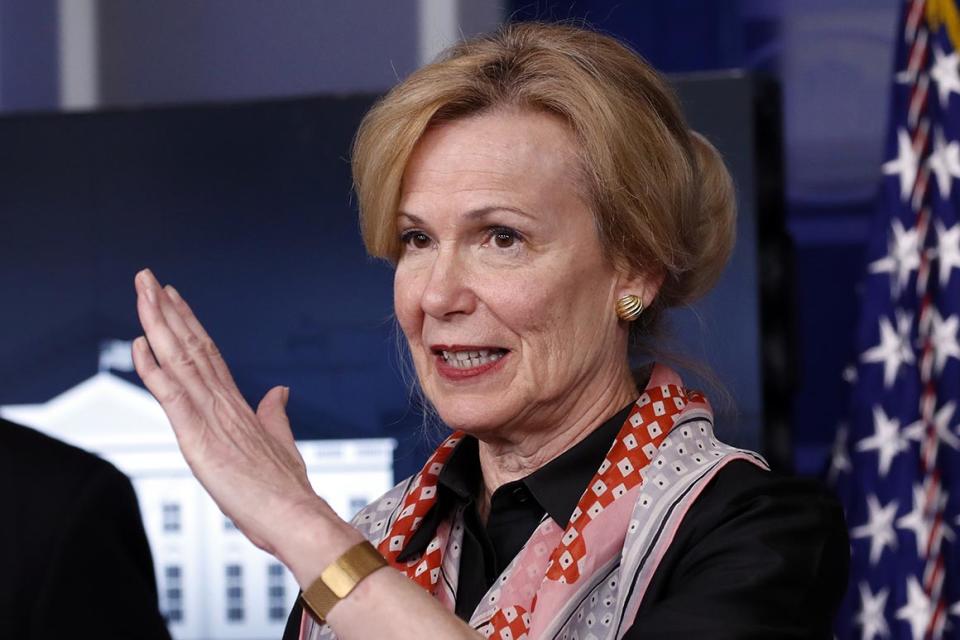

The problem has reached the highest levels of the White House’s coronavirus task force. In a recent briefing with reporters, Dr. Deborah Birx, one of the government’s top medical voices during the coronavirus crisis, warned Americans not to fall for fake companies promising tests.

“If you see them on the internet, do not buy them,” she said Tuesday. “Some of the tests available on the internet may have low specificity and give you a false reassurance they give you a false positive or false negative, implying that you may be protected.”

A rapidly spreading virus presents endless opportunities for scammers. There is little information about how to treat and control the disease, directions from governments are shifting regularly and there are troubling shortages of basic medical equipment. Some segments of the country are also distrustful of health authorities, creating a vacuum for alternative solutions.

Donovan has noticed that the more effective scams target the “worried well” — people who may not have coronavirus, but are terrified of catching it — such as the social-distancing app.

And with millions of Americans out of work, fraudsters “specifically targeting people who are financially insecure,” Donovan added, noting that she had seen credit card and government loan scams pop up.

“They do tend to happen after there has been a widespread outbreak of something or some other kind of tragedy,” she said.

Those types of scams flourished even before Covid-19 was deemed a pandemic.

Government officials went after Infowars’ Alex Jones for selling a toothpaste he claimed could kill coronaviruses and slapped down televangelist Jim Bakker for claiming his products containing silver could kill the virus on contact. They’ve also chased after countless others hawking essential oils, tinctures and teas.

Already, consumers have lost $12 million to these scams, according to Richard Cleland, an attorney in the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Consumer Protection.

Without stricter regulation of what can and cannot be sold in the U.S. to combat the coronavirus — as well as higher consumer awareness — Donovan warned that these scams will proliferate until a vaccine is developed, which will likely take at least a year.

“If someone's seeking information about symptoms and they're in distress already,” she said, “you can imagine how quickly that could go downhill.”

Daniel Lippman contributed to this report.