Coronavirus outbreak isn't the first calamity the NFL has confronted

Billions of dollars are riding on it, along with the hopes of millions of NFL fans. Every indicator points to there being pro football games this fall, even in the midst of this country’s biggest health crisis in generations.

“If there's a way for a team to be on the field and play football, they're going to do it,” Hall of Fame quarterback Steve Young said. “All the rest of it, we can talk about it and wonder if it will be OK or not. But as long as it's legal, it's happening. You just know that.”

The NFL has experience with seasons derailed by black swan events, persisting through crises involving natural disasters or man-made meltdowns. There were the strike-shortened seasons of 1982 and ’87, with the Washington Redskins both times emerging as Super Bowl champions. Teams have been displaced or disrupted by hurricanes, fires, and snowstorms.

“My bet would be that the National Football League fully intends to play its games, and fully intends to have its postseason and Super Bowl unfold in whatever quantity they can get that done,” said Frank Supovitz, the NFL’s former senior vice president of events. “I would think they’d expect to get all 16 games in, even if they lose a few preseason games.”

Not everyone is so sure.

“We think we’ve got to take care of the fans, and OK, that’s great,” Rams tackle Andrew Whitworth said. “But one guy’s kid gets coronavirus, and they come back and give it to the team. I don’t care what kind of hygiene you do, that’s going to happen.

“We’re all in close contact, sweating all over each other to play football. Sweat, spit, blood, you name it. Until that’s solved, until there’s not a 14-day quarantine for people who get it or are in contact with it, there’s no possible way football can go on.”

The NFL has weathered some significant challenges before. In past years, with the most turbulent ones, trudging forward required some creativity and painful sacrifices by the league.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina turned the New Orleans Saints into nomads. Unable to use the Superdome, the Saints played four of their home games at Louisiana State’s Tiger Stadium in Baton Rouge, three at the Alamodome in San Antonio, Texas, and one at Giants Stadium.

With apologies to the Dallas Cowboys, the Saints were America’s Team that year, and the NFL strived to make them feel at home in East Rutherford, N.J. — at least for pregame. Giants Stadium was festooned with Saints banners. There was a jazz band, and an especially heartfelt rendition of the national anthem.

Then, the game started, the Saints fumbled the opening kickoff, the New York Giants recovered, and the crowd roared its approval. New Orleans players — Saints elsewhere — were booed the way any other visiting teams would be.

Charity only goes so far.

“Traveling out here was uncalled for,” New Orleans quarterback Aaron Brooks said in the wake of the 27-10 defeat. “Try not to patronize us next time and tell us it’s a home game. But those were the circumstances and we lost.”

In that case, the NFL found a way. And that’s what people are expecting this season, when new stadiums are scheduled to open in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, and the league is positioning itself for its next batch of multibillion-dollar media deals.

Even if it means games are played with no fans in the stands because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and potentially with simulated crowd noise augmenting the broadcasts, the NFL is ready to go to extreme lengths to cobble together a season.

The league released its schedule last month, and built in discreet escape hatches and contingencies in case entire weeks of games have to be moved or even scrubbed. That blueprint for an accordion of a season was created in 2011, when a player lockout jeopardized the prospect of games. That labor crisis was resolved in the summer, however, so the league never had to use its backup plan.

The situation was different in 1982. A players’ strike that started in the first month of the season lasted 57 days, putting the season in peril.

Not all players were upset about that. The late Dwight Clark had achieved superstar status in San Francisco the season before, making “The Catch” in the playoffs against Dallas to propel the 49ers to the Super Bowl, which they won. He had a new contract, and a luxurious, three-level condominium in the heart of San Francisco that he shared with quarterback Joe Montana. Not only were the bachelors not charged rent, they were paid to live in the place.

Clark later called that stretch “the most incredible 57 days of my life.”

“We play two games and then go on strike,” he recounted in 2018. “And I’ve got that place, money, notoriety, and a Super Bowl ring. It was like being Huey Lewis.”

Eventually, the labor issues were resolved, and the NFL was able to squeeze in a nine-game season. The league devised a 16-team playoff tournament, with teams from each conference seeded 1-8 based on their regular-season records (and not how they did in their divisions). The Cleveland Browns and Detroit Lions made the playoffs that year despite losing records.

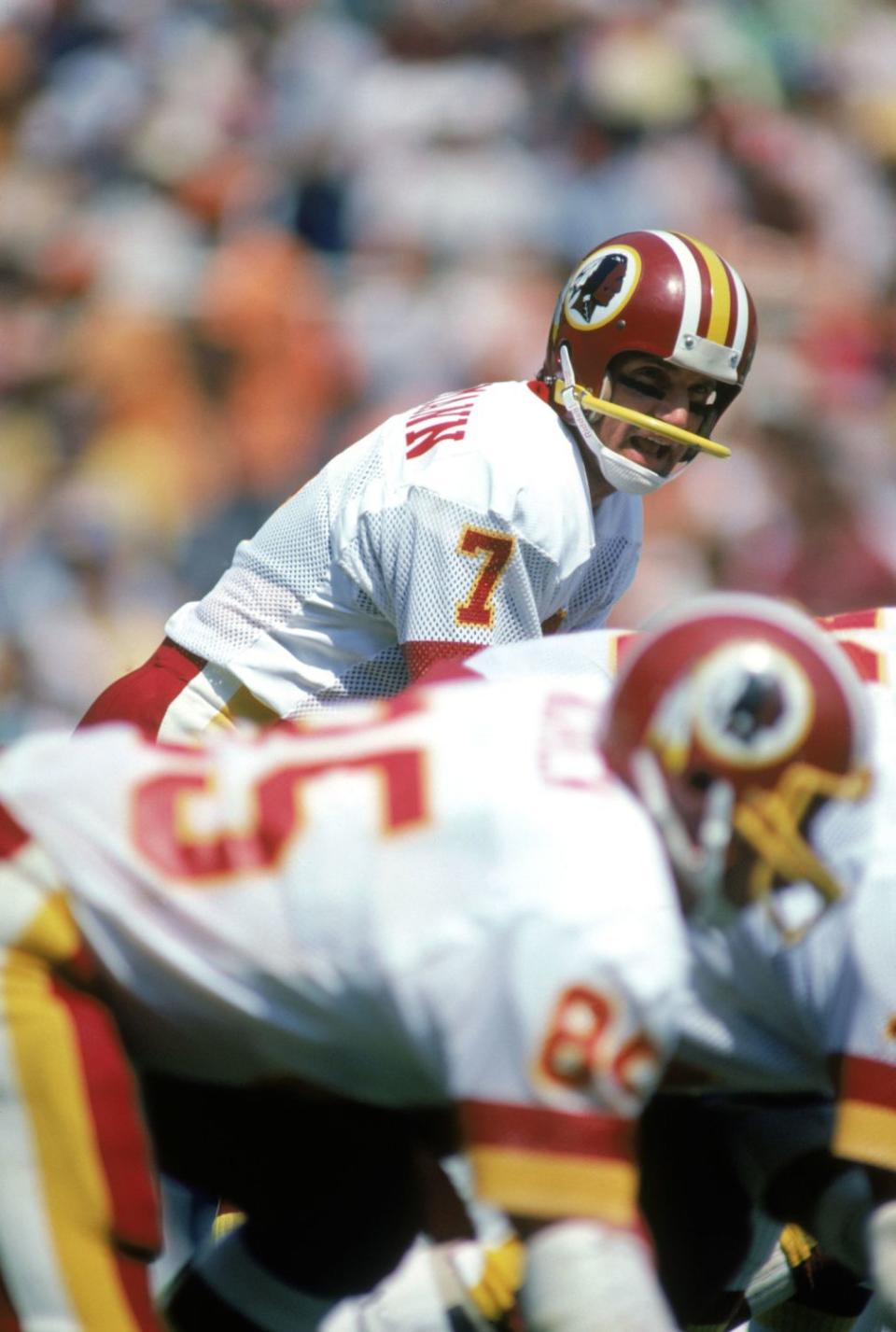

Despite losing all four preseason games, the ’82 Redskins went 8-1 in the regular season, losing only to the Cowboys. Then, they ripped through the NFC playoffs, beating three opponents by an average of 19 points. They finished the job with a 27-17 victory over the Miami Dolphins in Super Bowl XVII at the Rose Bowl.

Redskins quarterback Joe Theismann credits the work the players did on their own, during the nine-week strike, for keeping the team in tune and ready to hit the ground running when games resumed.

“I took the last game plan that we had, and we had organized practices three or four days a week,” Theismann said. “And for the first month, I had nigh on 40 guys show up. That’s the difference in a veteran football team. We went through basically a modified practice that coach [Joe] Gibbs would have held. We just did it on a high school field.”

The NFL has told teams that training camps this summer — if they take place — will be held at club facilities, as opposed to remote locales.

“The veteran coaches have a distinct advantage right now,” Theismann said, “because they don’t have to teach new systems, you’re not trying to change a culture. You basically have your playbook, and if you’re a veteran team, the players understand how to prepare. They’re professionals. Draft choices really don’t know what the game is about at that point.

“Guys like [quarterbacks] Joe Burrow and Tua Tagovailoa are going to be set back by this,” he said, referring to the top picks of Cincinnati and Miami. “Because they don’t have the offseason programs. And how much can you do on Zoom?”

There was another players’ strike five years later, but the league’s remedy was markedly different. Instead of wiping out games completely during the 24-day work stoppage, teams used replacement players. The third week of games was canceled, and the “scabs” played Weeks 4-6.

Approximately 15% of the regular players crossed the picket line to participate, including stars Montana and Roger Craig of San Francisco, Randy White of Dallas, Doug Flutie of New England, and Mark Gastineau of the New York Jets.

Buddy Ryan, in his second year as coach of the Philadelphia Eagles, urged his players to stick together, and they did, forming a picket line outside Veterans Stadium. Eagles replacements went 0-3, and the team wound up missing the playoffs despite a 7-5 finish by the real team.

Ryan opened a news conference after the scab portion of the season by presenting gaudy “scab rings” to team president Harry Gamble and his assistant, George Azar. It was a sarcastic gesture, a way of saying, “Thanks for nothing,” and Gamble felt Ryan embarrassed the franchise with the public shaming.

Unafraid of speaking his mind about upper management, Ryan referred to Eagles owner Norman Braman as “the guy in France,” in reference to the absentee Braman spending time at his villa there.

Dallas quarterback Danny White said the cumulative effect of the two strikes were a 1-2 punch that left Tom Landry’s Cowboys in shambles.

“I feel so strongly about this, that the strike had more of an effect of where our team went than anything else,” White told the team website in 2017. “Everyone wants to blame the draft for the deterioration of the Cowboys in the 1980s. I couldn't disagree more. It was the strikes, both in 1982 and 1987, how we handled them, and the fact that we never had a big team meeting afterward and aired out our feelings. We never patched things up. We were never a team again.”

Hall of Fame running back Tony Dorsett agreed.

“When the '87 strike started, we were one of the better teams in the league,” he told Cowboys.com. “We were thinking of another Super Bowl run. When we came back, we were nothing. We were broken.”

As for the Redskins replacements, they were all no-names — and they went 3-0, putting the regulars in prime position when the strike ended. They would go on to beat Denver in Super Bowl XXII in San Diego.

“We didn’t have a single player cross the picket line,” quarterback Doug Williams said. “I’ve always said, we might not have been the greatest team, but we were the best teams in terms of continuity. We believed in each other, and we stuck together through thick and thin, and that’s why everything worked out for us.”

The way Williams sees it, that Super Bowl victory is especially meaningful because of all the trials and tribulations he and his teammates had to endure to reach the mountaintop.

Whichever quarterback wins the Super Bowl at the end of the 2020 season might feel precisely the same way.