‘It’ll be brutal, man.’ Coronavirus has shut down Charlotte’s economy. Can it recover?

It was slow at first, then all of a sudden.

If you worked in a Charlotte restaurant, you noticed when reservations slowed the weekend of March 8. Then, as fear of the novel coronavirus spread, reservations were down by one-third the next weekend, according to data from the app OpenTable.

The next day, March 16, they were down two-thirds. A day later, Gov. Roy Cooper ordered all dining rooms across the state closed.

The coronavirus infecting the United States at an unprecedented rate has reshaped life for all North Carolinians.

Nearly 800 have the disease in North Carolina, with 259 of those located in Mecklenburg County as of Friday. There have been more than 500,000 cases globally, including at least 80,000 Americans.

While the pandemic has started to strain the healthcare system, actions taken to prevent widespread illness have shuttered much of the state’s economy, potentially harming it for years to come. Hotels, restaurants and shops closed en masse. Suppliers and manufacturers had orders drop and supply chains buckle.

With no idea of how long this would last, business owners have to ask themselves: Can I pay my workers? Can I make rent? Then, as the reality of the pandemic set in, they started to ask a third question: Is this it for me?

Since March 16, some 219,286 North Carolinians have filed for unemployment through Thursday. That’s more than any one month total in N.C. history, more than when the banks almost collapsed and more than when the mills closed.

We still don’t know what effect this wave of joblessness will have. We don’t know how long the pandemic will last. We don’t know how quickly people will go back to work when it does end or how fast hotels and restaurants will rebound.

But the shutdown already has had a dramatic impact on the economies of Charlotte and North Carolina. The data has yet to come in, but the state, and the country, is very likely in recession.

“If this is a four- to five-week event, then the damage to the economy may be quickly repairable,” said Barry Boardman, the top fiscal economist for the state legislature. “A prolonged event will result in cascading impacts across the economy both in the state, the nation and globally that could resemble the Great Recession.”

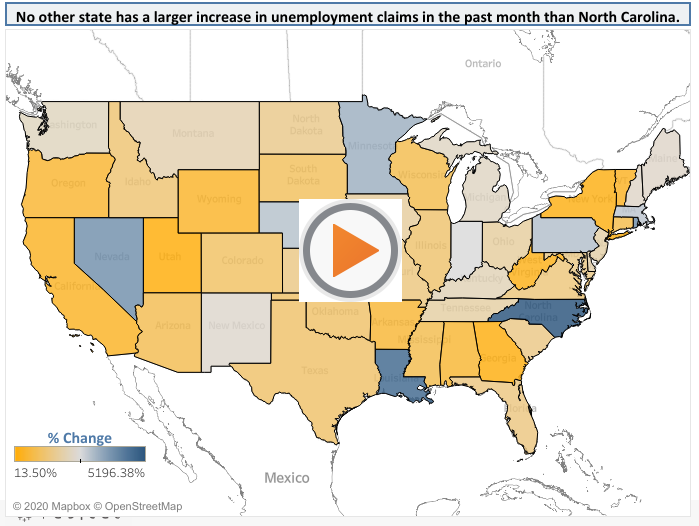

Already, North Carolina is becoming one of the states hardest hit by the economic contraction.

According to U.S Department of Labor data, no other state saw a larger increase in unemployment claims in the past month than North Carolina. Claims filed in North Carolina jumped 5,000% since the end of February, data show.

Interviews with more than 30 workers, business owners and government officials reveal how the coronavirus has already devastated the state economy, closing thousands of businesses, particularly restaurants and retailers, that might not reopen when the pandemic fades.

And the response from government officials, seen by some as limited, challenged and delayed, may stunt the coming recovery.

The front line

Restaurants, hotels and retailers were the first to suffer. Combined, the three industries employ one in five people in the greater Charlotte area.

“We went from 100% operational to zero,” said Katy Kindred, who owns the restaurants Kindred and Hello, Sailor with her husband, Joe. She’s cut her staff of more than 100 down to six. “This has affected us in a major way, and we were sort of first to bear the brunt of it.”

The average small business holds only about 27 days of extra cash, according to a JPMorgan study from 2016. Restaurants hold less, only 16 days on average.

Those 16 days are everything for a business.

Every restaurant in Charlotte is trying to make those days of cash stretch as far as they can. They can lay off workers, try to amp up delivery and maybe get a loan to tide things over. If they’re lucky, a restaurant might be able to make it through the pandemic before those 16 days expire.

But for many, that clock will run out.

“When we come out of this, we won’t see a lot of our favorite places, whether it’s a small brewery or a boutique,” said Janet LaBar, CEO of the Charlotte Regional Business Alliance, the top business advocate in the city.

“I am faithful that this community is resilient. But the uncertainty of how long we’re going to be in this is nerve-racking for businesses.”

One-third of Charlotte’s businesses said they couldn’t afford to operate without new sales for a month, according to a survey conducted by Labar’s group last week.

‘Nothing I can do’

While the community hunkers down, the layoffs have begun.

Some 815 people were let go by the vendor for the food tenants at Charlotte Douglas International Airport. The uptown steakhouse BLT Steak laid off 57. The uptown Hilton let go 162.

“There’s nothing I can do, there’s nothing I can control,” said Daniel Asbury, who was a bartender at Middle James Brewing Company in Pineville until he was laid off mid-March.

He and his wife only have a few months of savings, but it’s enough to make the mortgage on the house in Mint Hill and the car payment for a little. The longer the economy remains in stasis, the smaller those savings get.

Asbury applied for unemployment the day he was let go, but that application is still pending. N.C. workers are entitled to some of the most scant and restrictive unemployment benefits in the country.

While Cooper has eased some restrictions, the (Raleigh) News & Observer reported that only about 10% of people who applied for benefits actually qualified last year, and the average person received $264 a week for eight or nine weeks.

Still, some are able to weather the contraction without much difficulty.

On Thursday, March 12, Stratifyd, a Charlotte tech company with 108 employees, told its people that everyone had to work from home. That weekend, the company was pushing out one of its biggest system upgrades to clients across the globe.

But CEO Derek Wang knows he’s the exception, not the rule.

“The fortunate thing for us is that we are a tech company,” operating on a license basis, not by volume, he said. He worries about the small or medium-sized firms in Charlotte’s nascent startup ecosystem.

“It’ll be brutal. It’ll be brutal, man,” Wang said.

Daniel Levine, a Charlotte property developer, said some construction in Charlotte scheduled to start in the spring was delayed, while other projects continued as normal. But if the virus persists for months, he can’t imagine how the city will be affected.

America’s approach

Diseases like COVID-19 spread exponentially: one person can infect three others, who then infect nine people, producing a sharp curve of new infections.

If left unchecked, a disease that spreads this way can jump from a few thousand cases to a few million in weeks. That would destroy any healthcare infrastructure.

So, most decisions that cities and states have made as the coronavirus spreads — sheltering-in-place, closing dining rooms — have been, in part, to limit the number of interactions in society and flatten the shape of that curve.

There is another curve Americans have probably seen before: the U.S. unemployment rate. It slopes up and down through recessions and recoveries.

Many countries, like the U.K. and Denmark, are managing this curve by guaranteeing employees’ wages if companies don’t fire them. The U.S. is not doing this.

The stimulus package that passed Congress Friday injects an unprecedented $2 trillion into the economy and includes provisions that should discourage more layoffs and encourage some re-hiring. But it’ll come after the largest mass layoff in American history has already started.

Estimates range, but economists think that 20 million or more will lose their jobs in this recession. Last week, nearly 3.3 million people filed for unemployment nationwide, according to federal data. Many of those workers will lose employer-sponsored healthcare too.

“The workers are going to suffer a loss of earnings and wealth over that time period that will take years to recover from,” said Mark Vitner, senior economist at Wells Fargo. “If the Senate and House could have passed this package even quicker, businesses would have been able to hold on to workers.”

What can Charlotte do?

For the most part, Charlotte’s leaders have been waiting for the federal government to act, which will clear the way for state governments to act, then for cities and counties to act. That could lead to economic relief coming too late, some government officials, economists and business-owners warn.

No economic relief packages have been proposed at either the county or city level as of Friday. Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles said in a press briefing Wednesday that the city’s response to the economic crisis will be based on the federal government’s package.

“We will examine it for gaps and try to close those gaps,” she said. Property tax cuts and other spending are being considered, she said.

George Dunlap, chairman of the Mecklenburg County commissioners, was wary of cutting property taxes, which support county services like the health department handling the pandemic response. Dunlap, a Democrat, didn’t want to “bankrupt the government,” he said in an interview.

Still there’s concern among elected officials that local government has been too slow to act, and that serious economic damage has already been done.

“I want something in place last week,” said Mark Jerrell, a Mecklenburg County commissioner. “Every day that goes on is another day that someone has to close their doors, another employee gets laid off and another business is close to shutting their doors forever.”

There isn’t an economic relief framework in place yet, Jerrell said Thursday, although he was meeting with county officials Friday to discuss the issue.

Some counties are already moving ahead with large spending projects. On Monday, Gaston County announced a $50 million economic aid and relief package to combat the economic downturn from the coronavirus.

Charlotte officials, though, have yet to publicly discuss spending packages. Last Monday, City Council donated $1 million to a relief fund run by the Foundation for the Carolinas and United Way of Central Carolinas.

“Right now, we’re really in a mode of reacting to events as they are happening. We’re really not looking that far ahead and it’s hard to not just practice damage control,” said City Council member Ed Driggs.

Driggs, a former banker at Goldman Sachs, worries that it might not be possible for local government to effectively create a recovery plan because so much is up in the air.

“Where are we going to be a month from now? Who knows? Or three months from now?” he said. “In order for us to have a lot of future planning, we would need to have a trajectory.”

The SBA

One relief option for small businesses is a disaster loan from the Small Business Administration.

The loans can be used to cover regular costs that aren’t going to be met when a business is forced to shutter temporarily. That program, though, is straining under incredible demand.

The page to apply for disaster loans was so overwhelmed that it was taken down for maintenance, Eileen Joyce, a North Carolina SBA official, said in a presentation to small business owners this week.

Conrad Hunter, owner of Foxcroft Wine Co., a wine bar with three locations in Charlotte and one in Greenville, S.C., is familiar with the SBA application, having weathered the 2008 recession. He was three hours into the process on March 23 with more to still do.

“The site is overwhelmed and there’s no alternative,” Hunter said. An SBA loan will help him be able to start back up quickly, he said. Hunter said he laid off 108 of his 120 workers.

Joyce recommended business owners work on their applications on the site from 10 p.m. to 8 a.m., when traffic is lower. It will, though, take a couple weeks to get approved for a loan, she said. Longer still for the checks to arrive.

What’s next

While policymakers debate what to do, April 1st looms.

Rent’s due. Everyone from the soap shop in the mall to a freshly fired bartender will need to come up with rent or their mortgage unless they can get it deferred.

Many with a mortgage will be eligible for a payment deferral or forbearance, and some landlords have forgiven or deferred rent payments. The government’s plan to send out checks to Americans also will help some make do.

But to many, talk is just talk. They need help now. They want to make this work.

George Sistrunk, owner of Town Brewing in Wesley Heights, wants his brewery to survive. But he doesn’t have the cash stockpile that big businesses have.

“What I know is that we don’t have that backstop,” he said. “We don’t have a whole bunch of cash reserves to pull from in order to get through this.”

Observer reporter Alison Kuznitz and database editor Gavin Off contributed to this report.