Cost, red tape and cultural barriers keep glucose monitors from widespread use among diabetics

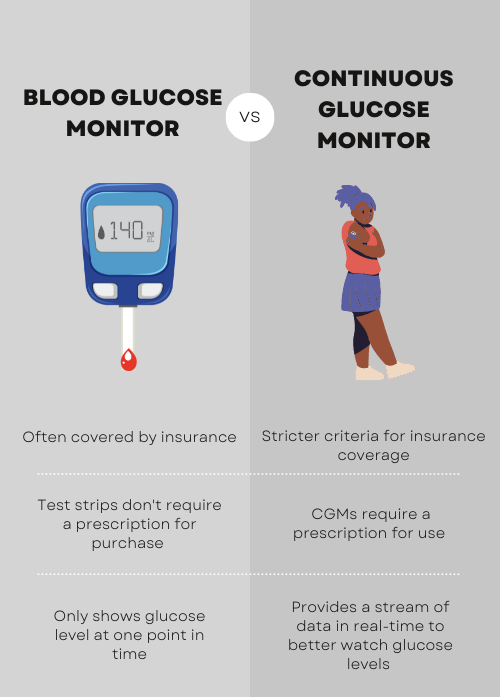

A continuous glucose monitor is a life-saving and revolutionary piece of technology: it collects much more useful data than other methods of measuring blood sugar levels.

For many diabetics, CGMs — mechanical devices that repeatedly measure the levels of sugar in a person’s blood — are a crucial tool. A small patch affixes to the skin on areas such as the arm or stomach, and the CGM transmits its readings to a sensor or phone, where the user can read real-time measurements.

They’re also expensive: Out of pocket, they can cost anywhere from $160 to $500 a month.

For the uninsured, CGMs can be nearly impossible to afford.

That’s part of a cycle of health inequities, according to Chinedum Ojinnaka, an assistant professor in the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University. Just because a device or treatment would make a difference to the patient doesn’t mean they are actually able to access that intervention.

“So you can imagine that an individual, for example, who is diabetic, goes to see a physician and has a medication prescribed for them. But they can't afford the medications, so they go back and they come back again with the same symptoms or worse symptoms,” Ojinnaka said.

“And you're prescribing the medication again without really addressing what the root cause of the noncompliance to treatment is. So at the end of the day, we engage in this vicious cycle where we're not really addressing the root cause and when the patient is progressively getting worse.”

While some insurance companies are moving toward covering CGMs for a broader group of diabetes patients, AHCCCS — Arizona's Medicaid program — covers CGMs when they are “medically necessary, cost-effective, and non-experimental,” according to Cliff Summerhill, a public information specialist for AHCCCS.

That means that for many on AHCCCS, prior authorization criteria limit CGM availability, which frustrates many health care providers.

“As of right now on Arizona Medicaid plans, on AHCCCS, it's very difficult and cumbersome to get coverage for a continuous glucose monitor,” said Casey Hilde, a clinical pharmacist who, along with 10 other Arizona practitioners, submitted public testimony in October 2021 urging AHCCCS to cover the devices for more patients.

Arizona's Medicaid program insures 20% of all diabetes-related hospital visits for inpatient treatment in the state and nearly a quarter of all diabetes-related emergency hospitalizations, according to statewide hospitalization data.

But care providers say CGMs make a significant difference in preventing hospitalizations.

“CGM makes a large (and) immediate difference in our patients' lives and is directly responsible for preventing hypoglycemic emergencies in several of my commercial patients. Not covering CGM is causing direct harm to diabetic patients and is a disservice to our patients and providers,” Hilde wrote in the testimony.

Lisa Beckett, a PharmD (advance practice pharmacist) who specializes in diabetes care at El Rio Community Health Center in Tucson, described another patient for whom a CGM is an essential, life-saving component of Type 1 diabetes management, but who does not have consistent housing.

“It is just a kick in the teeth trying to get this, because (the paperwork requires) a home address which she doesn't always have,” Beckett said. “I know it's gonna get approved. I know it's hopefully eventually going to get to her. (But) the journey is harder than I think it should be for AHCCCS patients across the board.”

Ernesto Huerta, of Avondale, has struggled for years to work with his insurance companies to provide CGMs for his wife and son, who both have diabetes.

Even with private insurance, Ernesto has spent hours on the phone trying to get access to CGMs in what he describes as a long and nightmarish process. The Huertas make too much to be on AHCCCS, but still can’t always consistently afford a CGM.

Blair Butterfield, a doctor of osteopathic medicine who also submitted public testimony, acknowledged that the financial barrier extends beyond just AHCCCS patients.

“Even patients with commercial insurance, a lot of them can’t afford or choose not to afford (their copay), and I understand. That’s a lot of money,” he said.

Sometimes, though, money isn’t the only factor affecting whether or not someone can get a CGM.

When money isn’t the only hurdle

David Grigsby spent much of his life monitoring his diabetes without a continuous glucose monitor. It took a particularly dedicated health care provider to persuade him to try the device that he says changed his life. But even after he realized how much he loved it, it wasn't always easy to access it.

Grigsby, a longtime resident of Tucson, was 22 when he found out he had diabetes. He had awakened one day with extremely high blood glucose levels, though he didn’t know it. He crossed the street to the 7-Eleven to get a Big Gulp.

After he drank it, he started feeling sick.

He called his mother, and she took him to the hospital. There, he says, he fell into a coma for about four days.

“When I woke up, I was like, ‘what's going on?’” Grigsby said. “And so the doctor was telling me that I'm a diabetic and things (are) gonna get kind of rough for a little while.”

Even after he was discharged, he was blind for over a week.

“I wouldn’t wish diabetes on my worst enemy,” he said. “Diabetes is nothing to play with. It can destroy you.”

Gradually, he got his vision back, but what followed was over 30 years of learning to manage his condition. And though continuous glucose monitors have been around for much of that time — the FDA approved the first “professional” CGM to be administered by doctors in 1999, and device companies were rolling out hyper- and hypoglycemia warning devices for diabetics’ personal use by 2004 — Grigsby didn’t start consistently using a CGM until last year.

There were a few things that made it harder for him to adopt the technology. When Grigsby first tried one, he still worked as a landscaper and he kept knocking the devices off while he was on the job. That frustrated him, so he gave up on the idea.

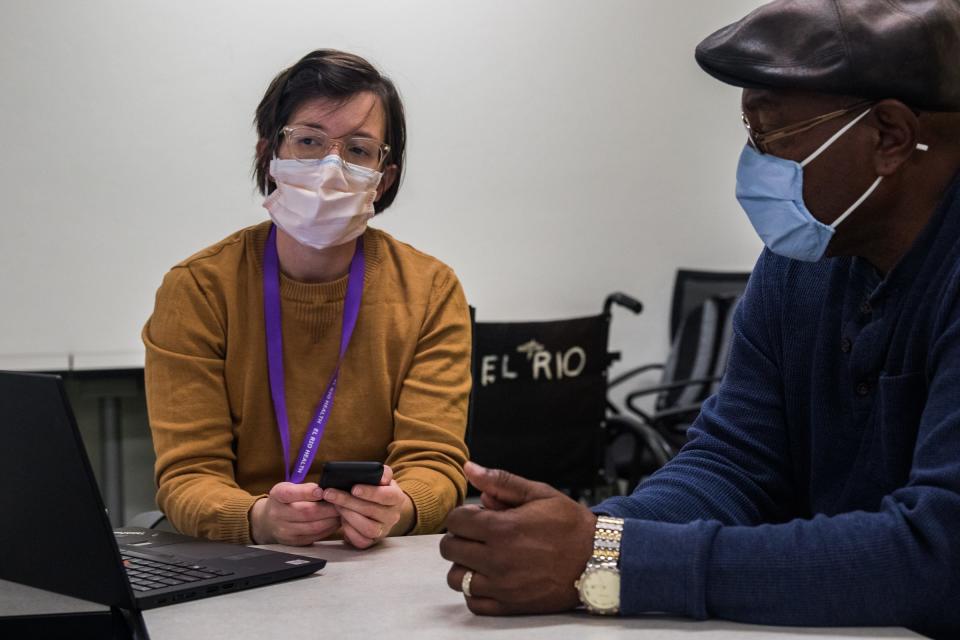

Grigsby was also skeptical of CGMs because he doesn’t use many electronics, and giving the CGM another try required the level of trust he had built up with his current practitioner, Beckett of El Rio.

He says a previous doctor was consistently late to his appointments. She often left him waiting in the exam room for over an hour, and when she did arrive, the time they spent together was brief — 10 to 15 minutes, at most. He wanted someone who made him feel valued and cared for.

“I don't like going to the doctor or the hospital, period, but it makes it easier to go if you know that … something's going to be done or somebody is listening to you,” he said.

Beckett and other health care professionals said that from their perspective, the time it takes to get someone access to a CGM, and then to help them learn to use it, is a significant hurdle.

“Time is a barrier, so it does take time to sit down and explain the devices how they work,” Beckett said.

But that time pales in comparison to the energy Beckett and other pharmacists and doctors must spend filling out paperwork to get CGM prescriptions approved. Even for patients who can afford it or do have insurance that covers a CGM, the process of getting one is complicated and burdensome, says Dr. Joy Mockbee, a family medicine practitioner at El Rio.

Mockbee says when she wants to prescribe a CGM, she has to navigate a wide array of confusing paperwork that is still often denied by insurance companies. It can take as long as 45 minutes on the phone trying to get prior authorizations approved. That’s valuable time that Mockbee says she can’t afford to lose.

“In the fast-paced clinic,” she said, “every minute counts as far as my ability to spend time with patients.”

Administrative hangups as well as historical patterns of discrimination and bias continue to plague the world of CGMs. Those patterns were recently exposed in depth in a study published by a team at Medtronic, a medical device company that makes insulin pumps and CGMs.

Over the period from 2017 to 2019, there was a significant disparity in access to CGMs between white and non-white Type 1 diabetics, said Dr. Robert Vigersky, an adult endocrinologist and chief medical officer of Medtronic Diabetes. What’s more, he said, his team found that the racial gap widened over those three years, even as more patients began using CGMs across the board.

Further studies will be needed to examine why the gap is widening, but Vigersky thinks the cost of the devices doesn’t capture the full picture.

“Cost is just one of the factors, and maybe not a major factor, in why there is this disparity in diabetes technology,” he said.

He suggested one reason might be a lack of endocrinology specialists.

“Endocrinologists are much more likely to use technology than those who are not specialists. And if (diabetes patients) don't have access to an endocrinologist because there aren't enough endocrinologists, you can understand why there might be a disparity,” he said.

Among physicians and in society at large, Heather Walker believes that unconscious bias may also be to blame. Walker, associate director of qualitative research at the University of Utah Health who has studied social elements of diabetes, said the stigma associated with diabetes, as well as weight-based stigma, intertwine with doctors’ expectations of their patients.

“Anti-fat bias and the idea that people with diabetes don't take care of themselves seem to originate from the same place. And they maintain each other also,” Walker said. "The main source of stigma comes from this idea that if you have been diagnosed with diabetes, it's because you don't take care of yourself. And if you have diabetes and you're not getting better, then you're continuing to not take care of yourself. And we have a ton of research that proves that narrative otherwise.”

That narrative plays into whether doctors will prescribe a CGM or believe that the intervention will work, she said, and cited recent research from a team at the Type 1 Diabetes exchange that found evidence of insurance- and race-based bias in the prescription of diabetes technology.

“Our medical system and our broader culture has very low expectations of people with Type 2 diabetes,” Walker said. “We don't expect that a person with Type 2 diabetes is going to utilize that (CGM) technology efficiently and in a way that's going to benefit them.”

And those factors are further connected to underlying or overlapping conditions. Devyn Thurber, a pediatric nurse practitioner who works with primarily Type 1 diabetics in Cochise County, said in the communities she serves near the border, intersecting social factors, including poverty and access to health care, coincide with greater mental health challenges.

“In general, mental health issues really tend to be more prevalent in the populations that we serve. And if you're depressed, you know, you aren't going to have that motivation to make lifestyle changes,” she said. “For the same reason, you're probably not going to have that motivation to be taking your medication every day and checking your blood sugar every day, too.”

That’s part of why advocates say CGMs could have such a big impact, particularly for populations that are perceived as “noncompliant” with finger stick blood glucose checking. But that perception has its practical limitations, and providers must navigate the gray area of balancing the possible benefits of a CGM with the factors at play in a patient’s life.

Beckett admitted she was more hesitant to prescribe CGMs in the past than she is now.

“I think I do get intimidated by having to get it covered by insurance, and I sort of want to make sure that someone is interested in it as I am, because there's a lot of calls you have to answer,” Beckett said. Still, she added, “I think my experience with it is that I am a little bit (quicker) to offer it now than I was when I first started (at El Rio).”

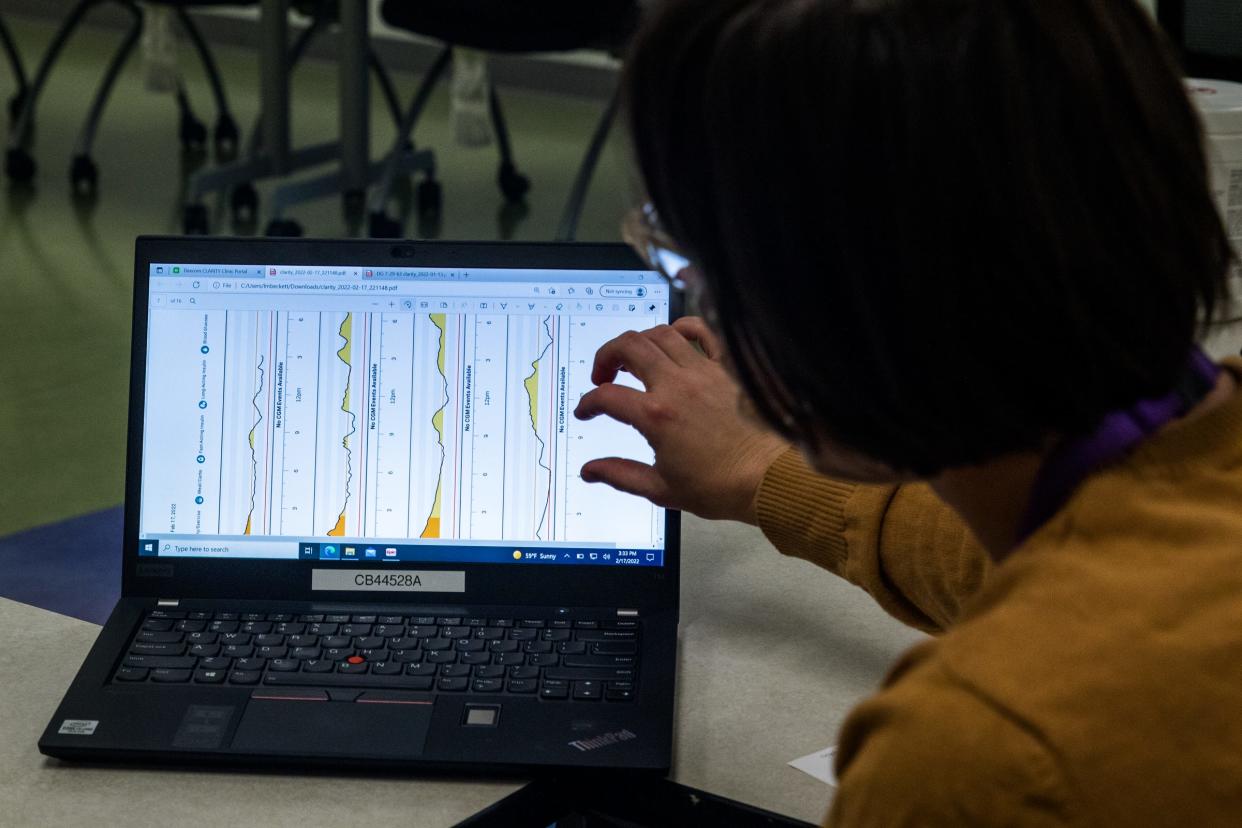

For the patients who can get CGMs, the wait is worth it: Grigsby said the past few months have been life-changing. At an appointment in February, in the glow of a computer screen full of CGM charts, he told Beckett that he’s working on eating “more vegetables, less bread.”

And he told her that he had gotten engaged to his longtime girlfriend, Linda. They were married on Mother’s Day.

“The last year has been my best year ever since (using the CGM from) Dexcom,” he said.

But for a few weeks this June, Grigsby said, he wasn't using a CGM. That’s because every year, providers have to renew prior authorizations, and due to a lack of clear communication between the medical supplier and the insurance company, Beckett said she had to start from scratch on getting Grigsby’s prescription approved.

“It feels pretty frustrating,” said Beckett, adding that she wishes insurance companies would acknowledge in their prior authorization criteria that diabetes can be a lifelong condition rather than something that changes every year.

Grigsby has a CGM again, but the time he had to go without one was still significant to him.

“I’m missing part of my life,” he said of time period when he had to go back to finger pricks. “If I’m using this machine to better my life, why are you playing with me?”

Cultural perceptions of CGMs

Wendy Andrade says a continuous glucose monitor saved her dad’s life, not just because it could provide biological data on his blood sugar levels, but because of the cultural issues it helped address.

Andrade, a pharmacist and realtor whose family is originally from Morelia, Mexico, and who now lives in Chicago, said her father Dagoberto was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes while she was still in pharmacy school in St. Louis. When she came home to Chicago to visit him, she found his blood glucose test strips unused, still stapled in the package from the pharmacy.

Dagoberto’s doctor had asked him about his blood sugar levels, but Andrade says that her father had been telling the doctor that his numbers were “good” despite his hesitance to use the finger prick device, an issue compounded by his fear of needles.

“He didn't get the proper education, as he should have from a pharmacist, on how to use it. That led him to noncompliance," Andrade said. "That led him to get dehydrated, to faint, to (be) hospitalized.”

So Andrade took matters into her own hands. She started researching continuous glucose monitors, and found that her dad’s private insurance would cover the device. Then she showed her dad how to interpret the blood sugar data. He started using a CGM in February 2020, and over the next year, she says the change was clear.

“When we were in Mexico, my whole family's telling him, ‘No, you eat all the tortillas you want,’” Andrade said. “And he was like, ‘No, I saw the numbers. I sat there and I ate and I’ll show you right now.’”

By modifying his eating habits and lifestyle, Dagoberto altered the course of his diabetes. Andrade says he had been experiencing vision problems that ceased when he was able to keep his blood glucose levels under control. She credits the CGM for improving not only her father’s health but also her experience as a caretaker.

“I think it is extremely life-changing. I think anyone should have it,” said Andrade. While she and her father had a combination of education and insurance that made getting the devices possible, she knows that many others do not. “Unfortunately, a lot of the (people) within the communities in the Hispanic-dominant (pharmacies) that I worked at did not have the opportunity to purchase or have access to the continuous glucose monitors.”

It’s a story familiar to David Marrero, the director of the Center for Border Health Disparities at the University of Arizona. Marrero says a combination of genetic, cultural and social risk factors — including access to health care, concerns over documentation status and cultural perceptions of illness — contribute to a higher prevalence of Type 2 diabetes in the Hispanic population. Diabetic patients of Mexican origin are also far less likely than those from other eligible groups to use CGM technology.

Marrero wants to know why. “Is it (an) issue with providers who don't want to prescribe it for whatever reasons? Or is it something that is a cultural-ideological issue for the Mexican-origin community? Is there something about this technology?”

With funding from Dexcom, Marrero is piloting a six-month study for patients with a history of poor diabetes control. While he is an advocate of the technology and believes that CGMs hold promise to help prevent or delay many complications of diabetes, Marrero said early hurdles associated with older versions of the technology, such as high cost and lower reliability, have shaped the thinking about who should have access.

While more insurance companies are beginning to cover CGMs for Type 2 diabetics, AHCCCS maintains prior authorization criteria at the health plan level, which is subject to AHCCCS oversight. In other words, approval may vary, but nationally recognized criteria factor in. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services still require that patients take insulin three or more times a day to qualify for the devices, which does not apply to many Type 2 diabetics who are not on insulin.

Since diabetics who are not on insulin can make do without frequent blood glucose data, Marrero said, Medicaid and Medicare have been less inclined to see the potential future benefits of granting CGM access to a wider demographic.

“The problem is that most of these complications are long-term consequences. You know, so I have diabetes now, but it may be 20 years before my eyes get crappy. And that's a weird paradigm, especially for people trying to cover costs,” he said.

But Andrade said the CGM helped her dad make immediate connections between diabetes and his own health, as well as the health of his community.

“He saw within our community of his friends, (someone) getting their feet amputated — like he physically saw that happen to somebody from diabetes," she said. "My aunt passed away from kidney disease, and she (had) ended up going blind because of the long-term, untreated diabetes."

Seeing her own risk factors led Andrade to decide to try a CGM for herself, alongside her dad. In a TikTok with 4.3 million views and over 500,000 likes, Andrade explained her dad’s condition and demonstrated how a CGM works.

As she tells her dad’s story in the video, she takes the CGM out of the box, pulls the cap off the plastic applicator, and takes a deep breath. Then she pushes the applicator against her arm, depositing a small white disk with the sensor inside. She gestures to the monitor and smiles.

In the comments, hundreds of people responded, many asking where they could find a CGM. “I wish we as Type 2 can get these two since it’s hard to check my sugar too due to my limitations,” one user said. “I need one how much is it I’m prediabetic,” another commented. Nearly 300 users liked that comment.

Andrade said she hopes to work with one of the CGM device makers, Abbott, to create more educational videos about CGMs. She said she has seen firsthand how the language barrier prevented her father from establishing a foundation of trust with his medical provider, and how her intervention helped him better understand his own condition.

“My dad just couldn't really explain or speak for himself” when he was at the doctor, Andrade said. “The language barrier is something that continuously is a problem.”

She has seen a lack of representation and mentorship in medical education as a first-generation Mexican-American. While she recognizes that CGMs are designed for people with diabetes, she said the experience helped her gain a new sense of empathy for her dad and her patients. And beyond helping her communicate to others about CGMs, using one allowed her to see the effects of specific foods and activities on her body, which she says gave her key information to help lower her own risk of developing diabetes in the future.

“Statistically and scientifically, I am high risk,” she said, citing her ethnicity as well as her family history for her one-time use of the device. “The benefit of this product is … you're going to see for yourself exactly what you're doing and what's happening inside.”

It’s a benefit other people without diabetes have begun to notice. As advocates push for the democratization of CGMs, some companies are making the devices accessible to a wide range of consumers, including non-diabetic athletes, fitness influencers and wellness junkies.

Not everyone is on board with that idea. Even on Andrade’s TikTok, some users pointed out that the device is intended for diabetics, and noted how some diabetics struggle to access CGMs. “I hope this doesn’t become a ‘trend’ so people who actually need it don’t have to struggle accessing it,” one comment reads. “Genuinely these are so expensive I’m (not) sure how you can afford to have them casually? That’s a privilege,” another says.

Andrade says her goal was to be a positive source of representation and education, and that the video serves a need. “Here's my experience, and here's maybe how it can help somebody else,” she said. “It’s always a mission to just give back and help others through sharing my story.”

But other non-diabetics are starting to use CGMs regularly, and not just as an educational tool. Some hope to find holistic solutions to a wide range of medical conditions. Others want to use the tracker as a weight loss tool. Still others want to “optimize” their athletic performance or create highly personalized meal plans for their unique bodies.

The science is new, and the claims are bold. But the mass adoption of CGMs may still be out of reach — and whether that’s a worthy goal is still up for debate.

In the next story: Monitors gain popularity among fitness enthusiasts while diabetics struggle to get one.

Republic data reporter Justin Price contributed to this article.

Independent coverage of bioscience in Arizona is supported by a grant from the Flinn Foundation.

Melina Walling is a bioscience reporter who covers COVID-19, health, technology, agriculture and the environment. You can contact her via email at mwalling@gannett.com, or on Twitter @MelinaWalling.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Cost, red tape, culture prevent diabetics from using glucose monitors