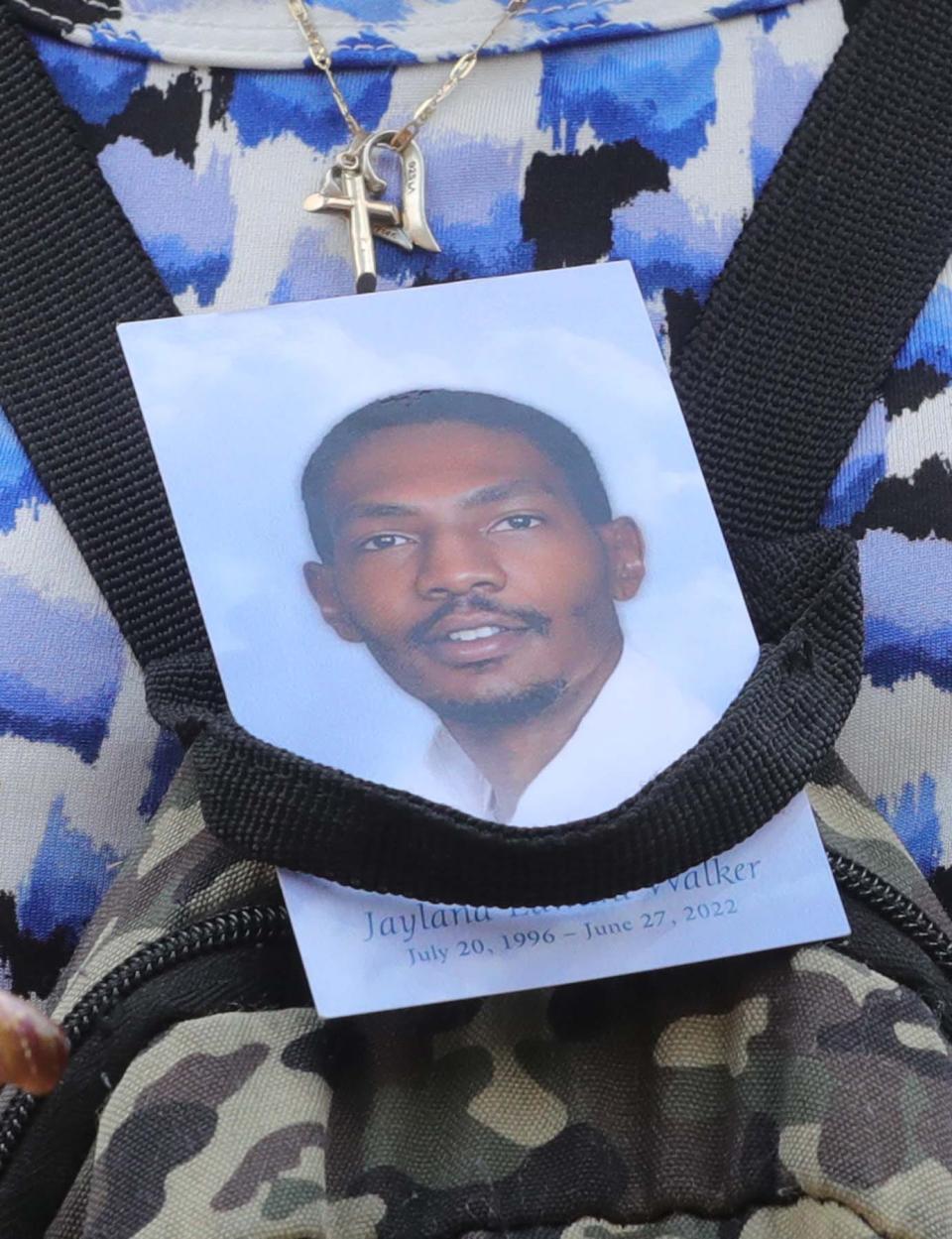

Could Cincinnati offer Akron a road map forward after Jayland Walker's death?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Timothy Thomas was shot and killed by Cincinnati police in 2001 when Jayland Walker was 4 years old in Akron.

Thomas was the 15th Black man or child killed by police in that Southwest Ohio city between 1995 and 2001.

No one knew it then, but his death and the riots that followed would forever change Cincinnati and how police there do their jobs.

Now, 21 years later, could Walker — who died last month in a barrage of police gunfire — do the same for Akron?

Cities across the U.S. in recent years — Chicago, Baltimore, Philadelphia and others — have tried to change how their police departments work and interact with their communities with varying success.

In Akron, some reforms targeting safety and transparency were already in the works after local and national outrage over the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police.

Akron's City Council passed new laws banning chokeholds and requiring Akron officers to intervene if they observe police misconduct. Voters approved a charter amendment requiring police to quickly release police body-camera video. And there’s a proposal now for a citizen’s review board, along with other measures.

All of these moves are in the right direction, some outside observers say.

But if Akron or any other city or town wants to change the fundamental relationship between police and the community — particularly with Black and brown residents — it needs to rethink the whole mission of policing, said former Cincinnati Police Chief Jeffrey Blackwell.

“What needs to happen in cities big and small, police departments need to return to community service over law enforcement,” he said. “When you get to know people, they start to trust you.”

And perhaps no other American city has tackled that like Akron’s neighbor 230 miles to the southwest, Cincinnati.

Long before George Floyd, there was Roger Owensby Jr. and Timothy Thomas

Former Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley remembers everything that led up to the 2001 riots that threatened that city’s future.

In 2000, while Cranley was serving his first term on Cincinnati City Council, tensions began rising in November when police stopped and searched Roger Owensby Jr. as he went to a gas station to buy an energy drink.

After 15 minutes, Owensby — a 29-year-old Black man who had served as a sergeant in the U.S. Army during the first Iraq war — ran from officers and was tackled, handcuffed and put into a cruiser before he died.

The Hamilton County Coroner said Owensby either suffocated from a chokehold or from officers piling on top of him.

Then, four months later, Cincinnati police shot and killed Timothy Thomas in an alley April 7, 2001.

Thomas was only 19, but he had already been pulled over by Cincinnati police 11 times and cited for 21 violations, mostly for not wearing a seat belt or driving without a license.

When Thomas ran from police that April, about a dozen officers followed him over fences and between buildings until he ran into an alley where a patrolman shot him.

The patrolman said he fired because Thomas reached for his waistband and he feared Thomas had a gun. But Thomas was unarmed and an investigation would later show he reached for his waistband only to pull up his baggy pants.

Protests followed and quickly evolved into three days of rioting.

It was the first wide-scale racial violence in a large U.S. city since the 1992 Los Angeles riots after a jury there acquitted police of beating Rodney King, a Black man who famously tried to calm his city by asking “Can we, can we all get along?”

By the time Cincinnati’s riots ended, about $3.6 million in damage was done. A national boycott of downtown businesses followed, causing an additional $10 million in lost revenue.

“I was 26 or 27 at the time and it was heartbreaking because the city I grew up in and love was just going through an awful time,” Cranley said. “Having grown up with plenty of advantages, I had to confront the reality of (the city’s) racial issues.”

Temporary solutions, or permanent policing improvement?

When cities face such uprisings, they often rush to find solutions, experts say.

“Police usually adopt a couple of programs that have been successful elsewhere to connect to the community, but the department itself doesn’t change,” said Brandon del Pozo, a former New York City cop and Burlington, Vermont, police chief who now teaches about the intersection of public health and public safety at Brown University.

Police reform in Akron: From George Floyd to Jayland Walker, here's where police reform stands in Akron.

Police reform scorecard: Where Akron stands on implementing recommendations

And even when the U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) steps in and mandates change with what's called a consent decree, reform can be be slow.

In Ferguson, Missouri, for example, after police shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed Black man in 2014, consent decree included anti-bias training for police -and changes to practices that discriminate against Black people.

Yet five years after the shooting, a study by the nonprofit Forward Through Ferguson determined little had changed in the police department’s culture or practices and pointed out that city had seven police chiefs during that time.

Cleveland, too, continues to struggle with a 2015 consent decree that came after the shooting deaths of Black residents Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams. More than 60 officers joined a 22-minute chase that ended with officers firing 137 shots into the car they were riding in, killing them both.

The consent decree, delivered just a little more than a week after Cleveland police shot and killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice, revealed that Cleveland police routinely violated peoples’ rights and used poor and dangerous tactics that placed officers in situations where avoidable force becomes inevitable, placing both officers and civilians at unnecessary risk.

Cleveland police were to make changes by 2020. However, the federal mandate has been extended with many of the reforms still not in place.

Akron, without a consent decree, has some opportunities for change, del Pozo said. In Vermont, where he served as chief, all police are trained by the same academy.

In Akron, police run their own training so the department can change how and what it wants its officers to know.

Generally, police do a lousy job training officers for stressful situations, he said, particularly when they’re touching others’ skin or feeling their sweat, which can trigger fight-or-flight impulses, he said.

The U.S. Army has great training for that because the cost of not having it, with the weapons soldiers routinely carry, can be devastating.

But training officers to avoid shooting situations altogether may be most important, del Pozo said.

“There’s de-escalation training that keeps both officers and people safe and that has been studied to scientifically work,” del Pozo said.

How Cincinnati's community, leaders worked to change policing

In the months before the 2001 Cincinnati riots, a group of local activists called the Cincinnati Black United Front and the ACLU of Ohio had joined a federal lawsuit alleging police had discriminated against Black people in Cincinnati for decades.

U.S. District Judge Susan Dlott had asked those groups and the police, the FOP union representing police and city officials if they would try to mediate the issue of racial profiling rather than litigate.

Fighting in court, the judge told them, would be long and expensive, and would probably only make matters worse because nobody would end up being a winner.

Then, after the riots, Mayor Charlie Luken invited the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) to analyze Cincinnati Police, which was key in what happened next, Cranley said.

Usually, when the DOJ comes in, investigators do a civil probe to see if a police department engages in a pattern or practice of unconstitutional or unlawful policing.

If so, the DOJ negotiates a reform package with the police department to fix systemic failures and a federal judge signs off on the legally binding agreement, called a consent decree.

“It’s important to have a relationship with (DOJ) from day one..say ‘hey, let’s do this together, ’” Cranley said.

A two-prong approach emerged.

As the DOJ investigated police shootings and use of force in recent years, the Black United Front, the ACLU, the FOP and city leaders began separately negotiating how to overhaul general policing, transparency and trust.

Some feared the negotiations would fail, particularly because of police pushback early on. But the federal court’s involvement made all the difference, said Cranley and Iris Roley, an activist and founding member of the Black United Front.

“We needed the stick and the carrot” to get the agreement done, Roley said.

The “carrot,” she said, was to “come up with our own reforms together, things we would own.” The “stick” was the federal judge making sure it got done.

A year after Timothy Thomas was killed, Cincinnati ended up with two agreements in April 2002.

Instead of a consent decree, the DOJ issued a memorandum of agreement that would change dozens of police operations related to the use of force.

Meanwhile, the Collaborative Agreement — negotiated by the community, FOP, police and city — changed how officers are trained, created a citizens complaint authority and added cameras to police cars, which was new technology at the time.

It also adopted something called a Community Problem-Oriented Policing strategy, with police partnering with the Cincinnati community, other governmental organizations and institutions to identify dangerous situations and find ways to reduce them.

“Part of putting the city back together again was not just telling the cops what they couldn’t do … it’s demoralizing,” Cranley said.

Cranley said they needed to spend an equal amount of time on what cops should be doing.

A simplistic example, he said, is stopping a kid for violating curfew on his way home from a library.

“Arrest him and you’ll piss everyone off,” Cranley said.

The same thing can happen if officers arrest someone for smoking marijuana in a city park and make it hard for them to get a job.

Refocus instead on “locking the guns and shooters up and the community will cheer you,” he said.

‘What happened was terrible,’ former Cincinnati police chief says of Jayland Walker

Blackwell, the former Cincinnati police chief, doesn’t hedge when talking about the Akron police shooting of Jayland Walker or the city’s handling of the aftermath.

“What happened was terrible…and I think it was wrong,” said Blackwell, who was deputy chief in Columbus before being named Cincinnati's chief in September 2013, 11 years after the Collaborative Agreement.

Two years later, after earning national praise for spearheading community policing practices and programs connecting police to the city's youth, the city fired Blackwell, saying he had retaliated against and abused employees.

Blackwell, who still has the support of many in Cincinnati's Black community, denied the allegations. The city paid Blackwell $255,000 and reclassified his dismissal to a resignation.

Blackwell, who now works as a police consultant, said Jayland Walker's death has already changed the city of Akron, and it's now up to Akron's police department to change with it.

Walker was shot after Akron officers tried to pull his car over for an unspecified traffic violation and equipment issue. Walker didn’t stop, however, and led police on a chase across town.

Police say Walker fired a gun once out of his car window during the chase, but it is unclear why or if he was aiming at anyone.

When Walker did stop, his car was swarmed by screaming officers with guns drawn. As Walker tried to run, officers first tried to shoot him with a Taser and then, when Walker appeared to turn toward them, eight officers fired off about 90 shots. Walker had 46 entrance or graze wounds.

Police said they feared Walker was going to shoot at them, but they later discovered he was unarmed and said they found a gun in his car.

Akron police shooting: FOP president says Jayland Walker wasn't just pulled over for just traffic violations

What we know about the officers: Here's what personnel files tell us about 8 Akron officers who fatally shot Jayland Walker

Blackwell, as chief, said he visited the mothers of every person police shot immediately afterward and apologized for the loss.

“I wouldn’t say whether we did anything wrong or not,” Blackwell said.

Blackwell said he would have told Walker’s family that Walker's death will change how Akron polices its community.

“When you shoot at a person 90 times, I don’t know how you make that right,” he said.

Building trust between the Akron police and the community it serves is not going to be easy, he said.

“Once the house is on fire, it’s too late to run out and get a bucket of water,” Blackwell said. “They need to really pivot.”

Trust mostly happens over time, he said, but there are some simple things Akron police could do immediately, like releasing the names of the eight officers who shot at Walker.

“The only thing (withholding names) does is sow the seeds of mistrust even deeper into the soil,” Blackwell said. “It reeks of 'big me, little you' politics. Police say ‘do what we want, we’ll tell you what we want and you just have to wait for information to be disseminated.’”

Akron’s Chief Steve Mylett has said he is withholding the names after the FBI received credible threats against the officers. But the Akron Police Department is also withholding the names of officers involved in other fatal police shootings where no threats appear to exist.

Blackwell emphasized it’s not just the community that needs to trust police. He said police need to find people in the community they can trust — residents who can help them be guardians of the neighborhoods.

Ninety-nine percent of the time, Blackwell said, police everywhere are chasing bad guys. Only about 1% is devoted to the good people who live there.

When Blackwell was a Columbus police commander, he said he made a point during roll call to ask officers if they could name a single person they dealt with on their beat or in their district.

“But they don’t know Ms. Brown who sits on the corner and drinks iced tea," Blackwell said.

“We’ve turned the police into a response force answering calls for service…and that doesn’t do anything to prevent crime or enhance community/police relationships,” he said.

Moreover, he said police need a better understanding of the deep-seeded fear of police, pointing out that policing has roots in Civil War America. Militia-style groups at that time had the power to control and deny access to labor, wages, voting rights and general freedoms of freed slaves.

Race and police relations: 'Fear is a real thing,' for Blacks when having to deal with the police officers

In the 1900s, police also enforced Jim Crow segregation laws.

“So that 16-year-old giving officers shade or disrespect because he’s been told by his great grandfather, grandfather and father that police will hurt you," Blackwell said, "so he’s afraid."

Cincinnati police 'a work in progress'

This summer, as protesters in Akron marched demanding justice for Jayland Walker, Cincinnati was hosting events celebrating the 20th anniversary of its Collaborative Agreement and how it has shaped police-community relations for the past two decades.

“This was the most important decision we made in my life in the city,” Cranley said of the agreement.

Not only was it the right thing to do, he said, the agreement also helped launch a Cincinnati renaissance.

Cincinnati, he said, is the only Ohio city of 100,000 or more other than Columbus that has had population growth since 1950. It also reduced poverty twice as fast as the rest of the state.

Roley and Cranley caution, though, that even 20 years later, the city policing model is still evolving and hasn’t fixed all issues.

Cincinnati’s Black residents, for example, continue to be disproportionately arrested and tension remains between some in the Black community and police.

“It’s not a utopia for Black people and police…Black people are still getting shot, so we’re still very much a work in progress,” said Roley, who was hired this year by the city of Cincinnati as the sustainability coordinator on issues related to refreshing the Collaborative Agreement.

Yet she and Cranley say there have been moments where they see just how far Cincinnati has come.

In 2001, the year of the riots, Cranley was a young city councilman and did a police ride-along and hung out with street cops after to find out what they were thinking. The officers told him “if they were able to do sweeps and roundups” or “crack some skulls” they could get crime under control, he said.

In 2014, 12 years after the Collaborative Agreement was signed and a year after Cranley was elected mayor, there was a crime spike. Cranley said he was in a meeting when another elected official suggested that police do sweeps and roundups to push back.

One of the cops who had been blowing off steam with Cranley in 2001 was also in that 2014 meeting, now as a high-ranking officer.

“He said, ‘In all due respect, I think that would be a mistake because it would set back our community relations’,” Cranley recalled the officer saying.

“You could have knocked me over with a feather," Cranley said. "I was rejoicing inside. It was such a sea change.”

For Roley, progress started revealing itself about five or six years after the Collaborative Agreement when people changed the way they talked about police and what they expected from them.

“If there was a police-involved shooting, they expected a press conference with information. If there was a problem, they knew there was a citizen complaint board…or that they could ask for a police supervisor if there was an issue,” she said.

After Jayland Walker's shooting, Roley said she’s talked to an Akron pastor and to the local NAACP about Cincinnati’s efforts, though she’s not sure how Akron leaders plan to move forward.

Meanwhile, Roley said she battles on in her own city.

Every day, before she leaves home, Roley said she has a silent conversation with Timothy Thomas, the man whose death led to riots and change..

“In my head, I ask him, are we doing well?,” Roley said. “He answers, ‘you just make sure that you don’t leave it…saving one life is better than saving none,’”

Beacon Journal reporter Amanda Garrett can be reached at agarrett@thebeaconjournal.com.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Can Cincinnati teach Akron about police reform after Jayland Walker