Could video gaming hold the key to better learning?

One might consider golf a silly sport. In simple terms, golfers get up early to hit tiny balls with big-headed sticks, then chase them long distances only to hit them again. They don’t develop speed, strength or agility. Mostly, they just walk and talk.

When you put it that way, golf sounds absurd. And yet, the National Golf Foundation estimates that nearly 40 million Americans played it in 2020. The reason: Golf is a brilliant game, argues Shawn Young, a former high school science teacher in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

Young offers three reasons why. First, there’s an objective; golfers count their strokes and try to improve their score over time. Second, there’s strategy; in order to reach their target, golfers have to choose which clubs to use and in which direction to aim. Finally, there’s socialization; golfers follow a dress code and congregate in clubhouses in search of community.

“Taking a ball and putting it in a hole is a pretty meaningless activity, but there’s all this other stuff around it — rules and structures that turn it into something people actually want to get up early on a Sunday to do,” explains Young, who says school should be a lot more like golf. “Educators are designing experiences that are meaningless to kids. They’ve designed school to control students when they need to design it to motivate them.”

To do exactly that, in 2013, Young co-founded Classcraft, a technology platform that helps teachers “gamify” their classrooms. Instead of extrinsic motivators that coerce students into positive learning behaviors — for example, grades — Classcraft nurtures intrinsic motivators like those inherent in video games. “Self-determination theory is the branch of psychology that looks at why we’re intrinsically motivated to do things,” Young says. “It’s been around since the 1970s, and game makers have become masters at it.”

Now is the perfect time for educators to also master self-determination theory, argues Barry Fishman, a professor of information and education at the University of Michigan, where he has built his own gamified-learning platform, called GradeCraft.

The COVID-19 pandemic, he points out, has ushered in a new era of online learning that will likely endure in some fashion for decades to come. But online learning is a “terrible game,” Fishman says.

“The reason it’s a terrible game is that it tries to replicate the basic elements of school but fails to recognize the added elements of difficulty,” explains Fishman, who specifies things like social isolation, ambient distractions, screen fatigue and poor connectivity. “Given the rapid shift to remote learning during the pandemic, it’s understandable that teachers tried to take what they were doing face to face and translate it to online. But moving forward, we have an opportunity to do things a little bit differently.”

Online and offline, education has come to a crossroads. If you ask Fishman and Young, the time has therefore come to game the system — literally.

What is Gamification?

Although games are a favorite tool in many classrooms, “gamification” is not about games. “Gamification is applying gamelike principles to nongame situations,” explains Stein Brunvand, associate dean and professor of educational technology at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. “For example, think about the rewards programs at your favorite retailers and restaurants. Their main goal is getting you to spend money, and they get you to spend money by giving you points that you can accumulate to get free stuff. It becomes a game without you even realizing it.”

Whether it’s a loyalty program at a restaurant or a math class at school, gamification at its best borrows the following principles from games in order to fuel intrinsic motivation:

Choice: Although most games have only one objective, there typically are many ways to achieve it. For example, different weapons, tactics or strategies to employ, or different challenges to pursue. What makes it fun is having the autonomy to choose how you reach the finish line. “A big part of gamification is providing choice,” Brunvand says. “Instead of giving 10 assignments that everyone must do, you can give a range of different assignments and allow students to pick and choose which ones they want to complete.”

Autonomy gives students the flexibility to select assignments that complement their learning style. “There are different ways to demonstrate mastery of knowledge,” Brunvand continues. “Some students might be inclined to do more writing-based assignments, while others may want to do something more hands-on, like creating a video animation or building a 3D model out of Legos.”

Competence: Games aren’t fun if they’re too difficult, if you don’t progress through them quickly enough or if you never win, notes Young, who says gamers and students alike are motivated by a sense of achievement — a feeling of competence.

“We’re motivated by our own progress,” he explains, adding that schools hinder progress by emphasizing grades over learning. “If I’m a C+ student, I usually get C+ grades. I’m still learning, but I never see my progress.”

In gamified classrooms, progress can be measured in points or other “additive” forms of recognition. “In traditional school, you start with 100 percent and try to maintain that,” explains Fishman, who says scoring anything less than 100 percent on assignments and exams subtracts from your total, which is punitive. “In a gameful system, you start at zero and earn points for everything you do. It focuses on what you’ve accomplished instead of where you’ve fallen short, which gives students a sense of progression.”

Community: Gamers like playing games not just because they’re fun, but also because they’re social, points out Matthew Farber, assistant professor of technology, innovation and pedagogy at the University of Northern Colorado.

“Kids want to feel like they belong,” Farber says. “If you watch TV shows like WandaVision or Bridgerton, they have huge online communities. When you’re done watching them, you can go online and read about all the Easter eggs, then share memes with your friends. That’s belongingness, and games do that really well.”

In gamified classrooms, then, learning often is a team sport. “School by design is very competitive, but we want to make it a more inclusive and collaborative experience,” Young says.

Turning Lessons into Quests

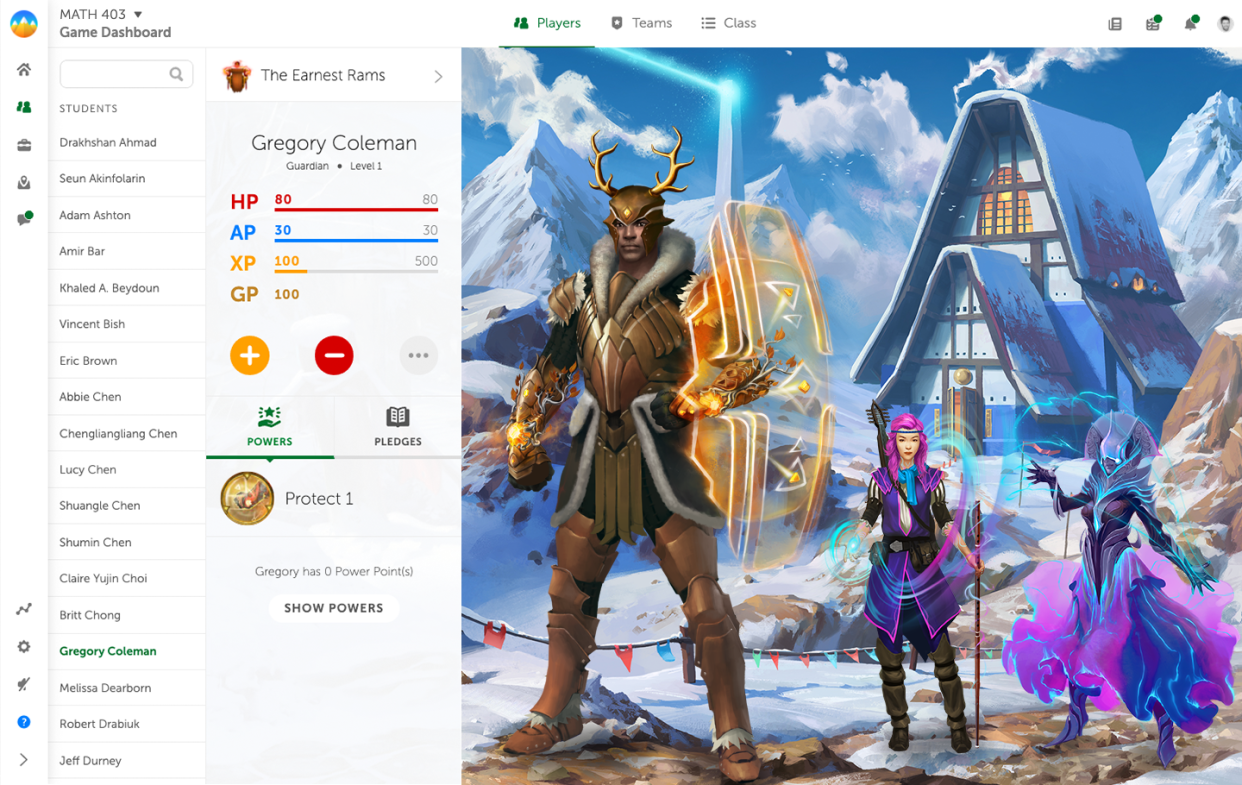

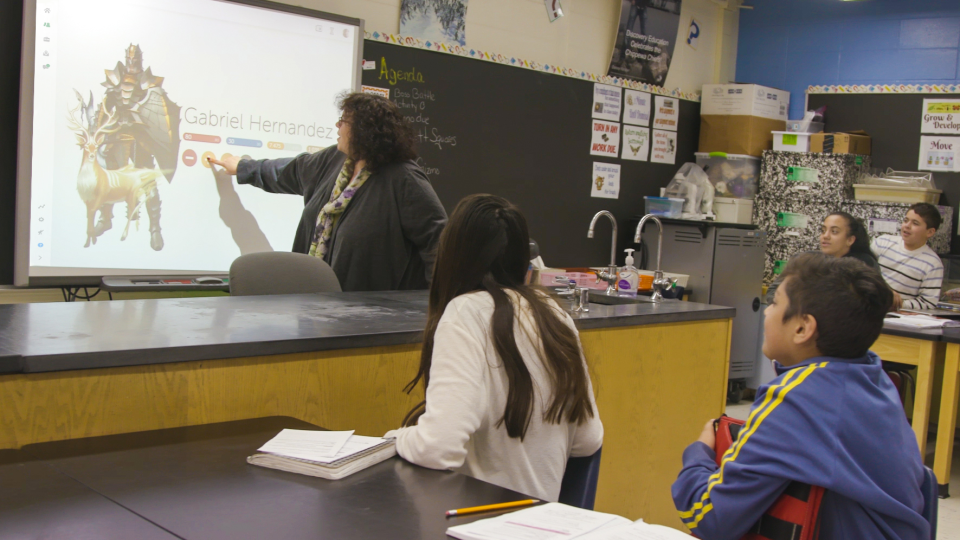

Michele Haiken, an English teacher at Rye Middle School in Rye, N.Y., has been using Classcraft to gamify her classroom since 2015.

“My entire school year is gamified. I have a storyline that drives my curriculum, and each unit the students engage in is a quest with different missions that they have to complete in order to practice their critical reading and writing skills,” explains Haiken, author of Gamify Literacy: Boost Comprehension, Collaboration and Learning.

Haiken awards points to students when they complete assignments and other activities, which they can subsequently cash in for prizes or special classroom privileges. “The more points my students earn, the stronger they become as readers and writers because of all the practice they’re getting.”

Like they would in a multiplayer video game, students work in teams, have characters and can “level up” as their learning progresses. When they master a concept, standard or skill, they can advance to new missions and earn badges that represent their progress.

“What I love about gamification in the classroom is that it creates a growth mindset,” Haiken says. “When they’re playing a video game, and their character doesn’t make it to the next level, kids don’t quit and say, ‘I’m done with it.’ They go back and try to figure out what they can do differently to get to the next level.”

Better Experiences, Better Outcomes

The benefits of gamification might be even more apparent in virtual classrooms than in physical ones.

“The problem with Zoom and many other tools we use for remote learning is that they mimic lecture-based classrooms, and lecture-based classrooms are not the best form of teaching because they make the teacher the focus instead of the student,” Farber says. “Gamification is learner-driven learning.”

What’s more, gamified classrooms can be customized to promote different learning behaviors, which can help students adapt to new learning environments like virtual school.

For example, teachers can award points to students not only for completing assignments, but also for showing up on time for video lessons, participating in online forums and discussions and communicating effectively through digital means.

“Kids don’t know how to be good distance learners, so we need to teach them what that looks like,” explains Young, who says scholars studying Classcraft have linked gamification to increases in student participation, improvements in grade point average and declines in behavioral problems.

“Whether it’s online or offline,” Young concludes, “the experience of school is core to student outcomes. If we can design that experience to be empowering and meaningful for kids, it will motivate them to do the things they need to do to be good learners. And that will lead to better academic outcomes.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How some teachers are gaming the education system