'It couldn't have snowballed at a worse time': 2020 US census under threat from coronavirus

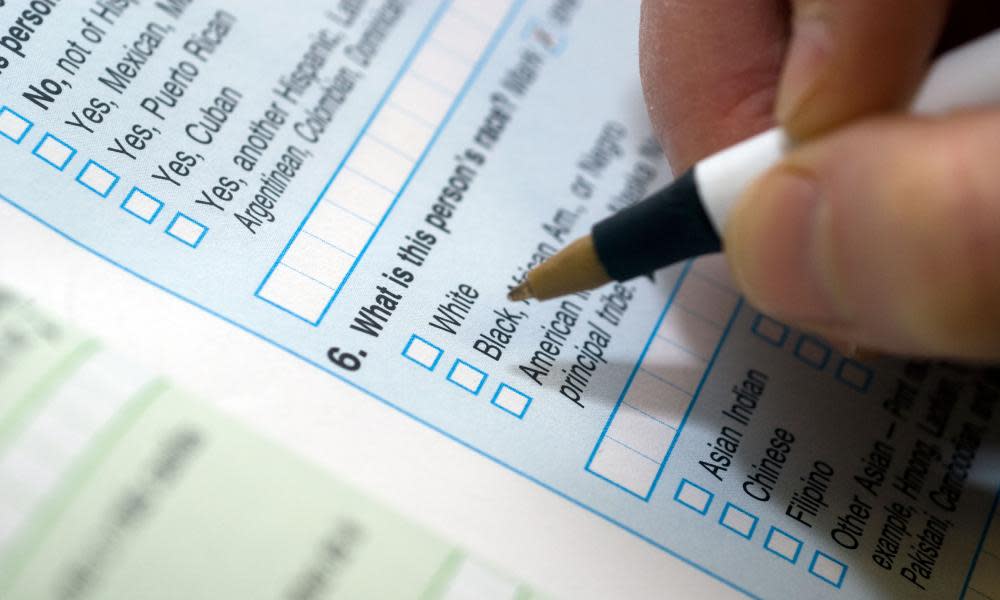

The coronavirus is upending the 2020 census, disrupting an already fragile operation that faced immense challenges in counting minority populations and other groups in the US before the outbreak of a global pandemic.

Americans started receiving invitations to respond to the census online, an option never offered before, or by phone on 12 March, just as governors and mayors started shutting down businesses and telling people to stay home. While the US Census Bureau is already delaying some of its operations, the US constitution mandates a decennial census and it cannot be cancelled. Federal law also sets 1 April as census day – the date at which the government must try to get as accurate a count of the US population as possible.

There are certain populations already vulnerable to going undercounted in the census, including minorities, immigrants and the poor. The outbreak will make it even harder, especially if the government is forced to scale back critical door-to-door operations to count people later this year. There is an ongoing push to get people to respond online now while they are quarantined at home, but swaths of the American population without reliable internet can’t do that. These issues build on persistent distrust among immigrants of the Trump administration, fueled by its unsuccessful attempt to add a citizenship question to the survey.

For now, elected officials and advocacy groups will have to find a way to persuade them to respond and to ensure they get counted without face-to-face contact.

“It couldn’t have snowballed at a worse time,” said Terri Ann Lowenthal, a consultant who works on census issues with lawmakers and advocacy groups. The further away from 1 April that the bureau counts people, she said, the more difficult it will be to collect accurate data, and 21% of US households have responded to the census so far.

An inaccurate count would have severe consequences. The data from the census is used to allocate $1.5tn in federal funds and determines where governments build hospitals, roads, public transportation and other infrastructure. It’s also used to draw political district lines in place for the next decade and determine how many representatives in the US House each state gets by 31 December. Depending on how severe delays are because of the Covid-19 outbreak, the Census Bureau may have to ask Congress to change federal law to extend that deadline, said John Thompson, the director of the Census Bureau from 2013 to 2017.

The Census Bureau is already pushing back some of its programs, including an operation to dispatch workers to heavily trafficked areas to help them fill out the census and another to count the homeless population as well as people living in nursing homes and prisons. The bureau also announced earlier this month it was delaying the final deadline for the count from 31 July to 14 August.

The bureau has also delayed the start date of a critical door-to-door count from mid-May to late May following up with people who don’t respond on their own. The program is critical to getting traditionally hard-to-count populations to respond to the survey. It is unclear how the bureau would proceed with that operation if current social isolation practices are still in place then.

This is “uncharted territory”, said Margo Anderson, a historian who has extensively studied the census. While the bureau plans extensively for emergencies, and has $2bn in contingency funds, it has never faced a pandemic during its peak operations. There is already concern that it will be increasingly difficult to count college students, who are supposed to be counted where they live and sleep most of the time, because many schools have closed their campus for the semester.

The lack of in-person interaction will probably make it more difficult for organizers to build trust in vulnerable communities. At the Arab-American Family Support Center, which serves immigrants and refugees throughout New York City, organizers planned to host in-person workshops about filling out the census. Those workshops are no longer happening, and the center is focused on the 1,300 people who signed pledge cards to fill out the census.

“It’s a level of being able to read a person and what their comfort level is and whether your message is getting through or not,” said Howard Shih, director of research and policy at the Asian American Federation. “It’s that face-to-face thing.”

In New York City, where 29% of households lack broadband internet, officials planned more than 300 “pop-up” centers – libraries and other public facilities – where people could use a computer to fill out the census online. But census organizers scrapped those plans and are now focusing on reaching people through text-a-thons and phone banking. Meanwhile, officials scaled back their subway advertisements as New Yorkers were discouraged from using public transportation and shifted to digital advertising.

“It makes it extremely difficult,” said Julie Menin, who is leading the city’s census efforts.

But New York officials have also realized that Covid-19 concerns can be channeled to highlight the importance of the census, and how it is used to get funding for healthcare services and hospitals. 23.4% of households in the city have responded so far, according to the Census Bureau. Nationwide, 33.1% of households have self-responded.

One of the biggest challenges facing the census now is simply getting messaging about it out at a time when news about the coronavirus is crowding everything else out.

So far, elected officials and advocacy groups have largely praised the Census Bureau’s efforts to mitigate the effects of coronavirus on the count’s operations. But the census, the largest peacetime mobilization of the federal government, is a carefully calibrated effort. The more changes there are, the greater the risk to its accuracy.

“It’s a little like Jenga. Every time you pull out a piece the structure becomes a little less stable,” Lowenthal said.