There Have Been Countless Elvis Movies, but There’s Never Been Anything Like Priscilla

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

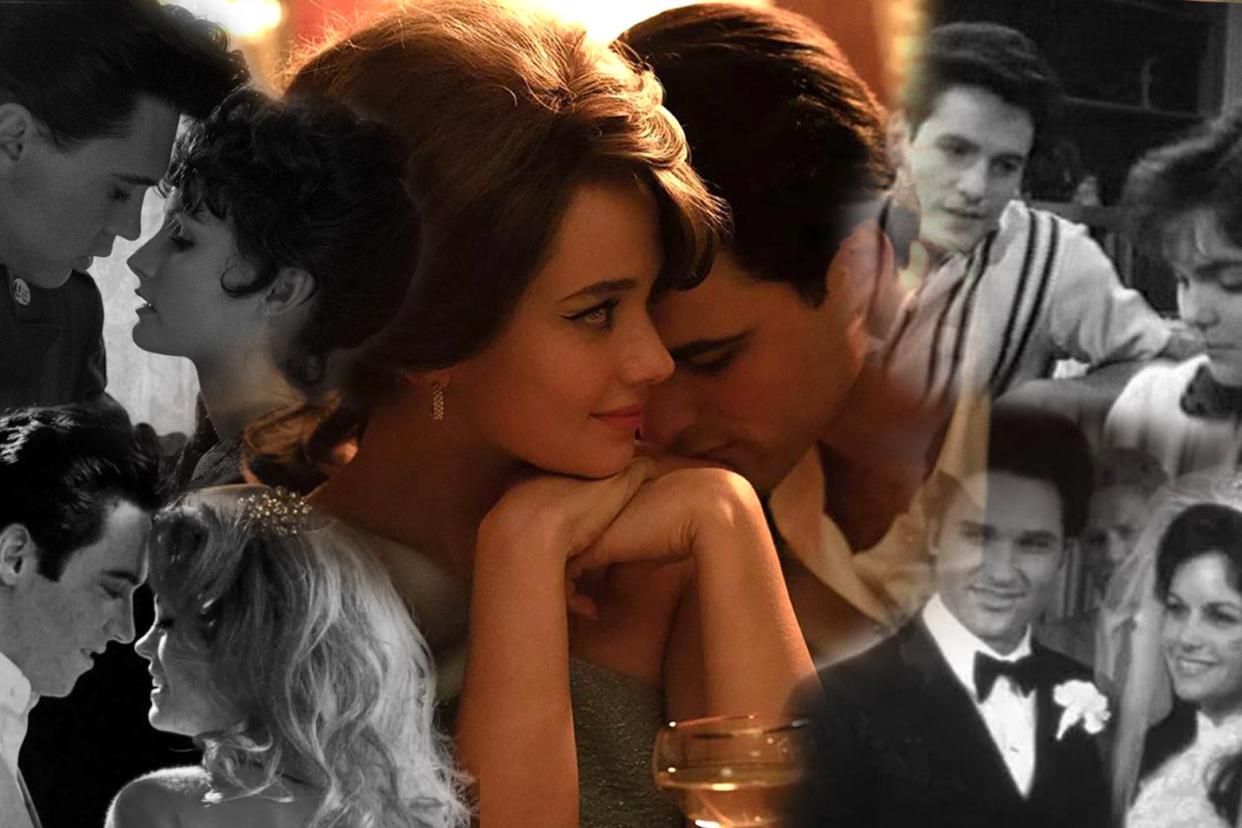

Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla is not the first time the story of the woman married to the world’s most famous man has been told, but it’s the first time she’s gotten top billing. Even in the 1988 TV movie Elvis and Me, which, like Coppola’s film, is adapted from Priscilla Beaulieu Presley’s 1985 memoir, she comes second, identified only through her proximity to greatness. Priscilla hews so close to Presley’s book that watching it next to the earlier adaptation is at times like seeing double—refracted several times over when you add in the many other filmed versions of Elvis’ story in which Priscilla ranges from co-lead to bit player. But the more versions you watch, the more Coppola’s stands out, both for its fidelity to Priscilla’s perspective and its resistance to treating Elvis like a myth instead of a man.

There are movies about Elvis in which Priscilla does not appear at all, and others in which she’s just a fleeting presence. In 1997’s Elvis Meets Nixon, Alyson Court’s Priscilla shows up just long enough to nag the King of Rock ’n’ Roll about how he’s spending his money. But it’s hard to find a more pointed contrast than the one between Priscilla and Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis, released last year. Olivia DeJonge’s Priscilla shows up about an hour into Luhrmann’s sprawling opus, meeting Elvis (Austin Butler) when he’s a GI stationed in Berlin and she’s the 14-year-old daughter of an Air Force officer. And the movie leaps over most of their first decade together. One moment, it’s 1959. Five minutes later, it’s 1968.

If Coppola is uninterested in Elvis the legend, that’s practically all Luhrmann the inveterate maximalist cares about. Luhrmann’s version is framed not through Priscilla’s point of view but through the morphine-dilated pupils of Elvis’ manager, Col. Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), who, when it comes to the control of his protégé and meal ticket, views Elvis’ love for Priscilla as “the most dangerous thing of all.” The Colonel’s only goal is to maximize Elvis’ short-term profit, pushing him to star in cheesy Hollywood movies and record schlocky ballads as his audience’s attentions slip away. Priscilla, by contrast, just wants what Elvis wants. Her job is to keep one eye on his dreams, the other on his progress toward them. “I think if you dream it, you’ll do it,” she tells him at the end of their first scene. Thanks to a Colonel-imposed hiatus from live performance, it takes many years for her to see him sing in front of an audience. When she finally does, she is dumbstruck. “I don’t know who that was up there,” she tells him. “You were incredible. You were everything.”

Luhrmann’s Elvis skips over the moment Elvis and Priscilla first met, and with it, any reminder of how young she was when it happened. John Carpenter’s 1979 TV movie, also called Elvis, plays out that moment, as Season Hubley’s Priscilla walks anxiously through the door of his living room and instantly locks eyes with Kurt Russell’s Elvis. The movie, released 18 months after Elvis’ death in August 1977, elides any mention of her age—she was 14; Elvis, 24—and no amount of awkward fidgeting can make the 27-year-old Hubley seem as if she’s still in high school. Cailee Spaeny, who plays Priscilla’s title character, is 25, but Coppola never lets us forget how young Priscilla herself is. Escorted to Elvis’ party by an associate tasked with finding young women to keep Elvis company, Priscilla spies her pop idol holding court and is star-struck. But it’s hardly love at first sight. Elvis (Jacob Elordi) pegs her as a high school student, but an older one, asking if she’s a junior or a senior. She responds, “Ninth,” and when that takes him a moment to process, she awkwardly clarifies: “Ninth grade.” He chuckles and replies, “Why, you’re just a baby,” and while she bristles at the characterization, we know he’s not far wrong.

The scene plays out almost identically in Elvis and Me, the 1988 TV movie, right down to the layout of the room. (Priscilla Presley is credited as an executive producer on both projects.) The effect, however, is profoundly different. Susan Walters, then a year younger than Spaeny, makes a convincingly teenage Priscilla, especially in a shapeless sailor dress and ragged ponytail, and when she objects to being called a baby, her frustrated tears make her seem even younger. But after Elvis moves to the piano to croon “Are You Lonesome Tonight,” she’s smitten, and we’re meant to be as well. The camera’s focus goes soft as she looks at him, her face beaming with light, and he turns to meet her gaze. This is the real thing. This is love.

Presley’s book presents Elvis as a manipulative and controlling man who kept her isolated and unsatisfied, insisting that they not consummate their relationship before marriage because he viewed sex as “sacred,” while enjoying several high-profile affairs and keeping her existence a secret from the public. But she also portrays theirs as a true and enduring love, one that outlasted even their marriage. Coppola’s movie is faithful to those ideas, without necessarily endorsing both. We see Spaeny’s and Elordi’s eyes meet across the room, and we know that they’re lovestruck. But the camera keeps its distance rather than coming in for a gauzy close-up, and instead of bathing them in the glow of young love, the scene is washed-out and dim.

The story of a young woman imprisoned by her privilege, Priscilla resonates most strongly with Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. But where that movie is flush with its subject’s carefree luxury, Priscilla is heavy with the weight of unmet promises, the dream of a life that’s never quite realized. Compared to the sprawling, sunlit Versailles, Graceland is gloomy and closed off, too cramped to give Priscilla and Elvis a moment’s privacy when the house is crammed with hangers-on, even more confining when he hits the road and she’s left alone. After Elvis persuades Priscilla’s parents to let her finish up high school under his roof, she moves into Graceland for good, but his father wastes no time laying down the law: “No strangers at Graceland,” he tells her, meaning no friends of her own. She’s a queen without a court.

Even the versions of Priscilla’s story that aren’t officially taken from her book repeat its incidents, like the exchange where Elvis phones in to ask her to “keep the home fires burning,” and she, fed up with his absences and his lack of attention, responds, “The flame’s burning on low.” But the accounts don’t always stay with her perspective. In Elvis and Me, Presley writes about an incident in which Elvis asks for her help evaluating a stack of demos for his next album. After growing increasingly frustrated with the songs the Colonel and his record label are sending his way, Elvis finally finds one he likes, but for Priscilla, it lacks the “catchiness” that had made her a fan in the first place. Elvis flies into a rage, hurling a chair in her direction, and although she manages to step out of the way, one of the records that had been piled atop it flies off and hit her in the face. He apologizes within seconds, but by now she is beginning to see his mood swings as a tool and not just an inevitable result of inheriting his mother’s temper.

The confrontation shows up in Carpenter’s 1979 movie, but the focus is on Elvis’ frustration, not his physical intimidation. Instead of a chair, he flings a lamp to the floor, and she immediately rushes to comfort him, advising, “You can’t keep it inside. You gotta let it out.” In the 2005 miniseries, once again called simply Elvis, the threat of violence is actualized, but Priscilla isn’t even in the room: In a fury over losing teenage fans to the British Invasion, Elvis (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) hurls a pool cue at a woman who suggests that his music might be a bit behind the times. The cue breaks her ankle, but Elvis’ victim stays anonymous, identified only as the wife of a man in his entourage.

Priscilla tones down the violence slightly, in that Priscilla emerges from the incident unscathed. But you can still feel the threat as the chair bounces off the padded wall near her head, the impact forceful enough to leave a pronounced divot. It’s the only portrayal to place the emphasis on Priscilla’s vulnerability rather than Elvis’ rage, to the extent that when the chair hits the wall, he’s not even on screen. The power differential is inherent in every shot where the 6-foot-5 Elordi looms over his 5-foot-1 co-star, but Spaeny’s Priscilla doesn’t comfort him after his outburst. She learns that the best way to counter his aggression is to deflect it rather than rise up against it. Elvis abruptly proposes a trial separation when she’s several months pregnant with their first child, and instead of reacting with the expected outrage, she simply asks how soon he needs her to leave. She’s barely left the room when he calls out down the hallway that he’s had a change of heart.

There’s no separating Priscilla’s story from Elvis’, and although she has lived nearly 50 years after his death, the tellings tend to stop when he does. Even Elvis and Me, which devotes 15 minutes to Priscilla’s pre-Elvis childhood, ends with a montage of Elvis photos—what’s an “and me” without its famous precursor? But when Priscilla is done with Elvis, Priscilla is too. After she leaves him in a Las Vegas hotel room, a stray tear hanging from his nose, we never see him again. She packs up her things alone, and as she drives away from Graceland, we sense that this is the beginning of a story, not just the end of one. Like Luhrmann, Coppola scores their farewell to Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You,” a song that Elvis wanted to record but never did, because Parton refused the Colonel’s demand to sign over half her songwriting royalties in exchange. (Parton’s resistance, like Priscilla’s, paid off: The song reportedly earned the singer $10 million in the 1990s alone.) Luhrmann uses it as a pledge of undying fealty, with Elvis whispering the refrain to Priscilla as they part for the last time. Priscilla hears Parton’s verses as well as the chorus, the ones that explain why this pledge must also be a farewell. “Bittersweet memories,” she sings as Priscilla passes through Graceland’s gates, “that’s all I am taking with me.” She will love him forever, but she has to do it on her own.