This courier had places to go, people to see so Day of Thanksgiving had to wait

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Courier James Wilkinson plodded along, his saddlebags enveloping important documents.

They detailed the British Army’s surrender that would help determine the course of the American Revolution.

It was mid-October 1777 in upper New York, and Wilkinson was ordered to deliver battlefield reports about the surrender of 6,000 British and Hessian soldiers to American forces at Saratoga. His orders didn’t say when they must be handed to an anxious Continental Congress, America’s legislative body meeting in York about 335 miles away.

Good thing he wasn’t given a delivery deadline, because he had places to visit and people to see along the way. First, the 20-year-old officer stopped in Easton to court Ann Biddle, daughter of a prominent Philadelphia family. This slow courier was better as a courtier, for the young woman later became his wife.

In Reading, he recklessly revealed part of a letter written by Thomas Conway, a disgruntled officer under Continental Army Commander in Chief George Washington. The letter, fueling a loose-knit conspiracy called the Conway Cabal, labeled Washington as a “weak general.”

American forces under Gen. Horatio Gates beat the British at Saratoga, and Washington’s Continental Army wasn’t scoring battlefield wins anywhere in those days. Some officers started to choose sides, and one of them, a Washington ally, learned of what came from Wilkinson’s loose lips and alerted the commander in chief.

As all of this was going on, unconfirmed reports of Saratoga success were reaching York.

But Continental Congress needed the confirmation from Wilkinson, wherever he was.

“We have spent three days soaking and poaching in the heavyest rain that has been known for several years …,“ Continental Congress delegate John Adams, impatient for official news, complained from York.

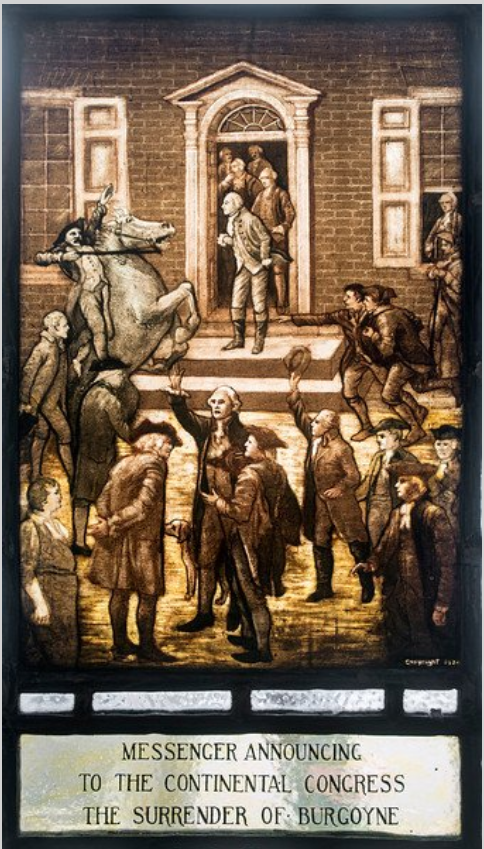

At last, after two weeks, Wilkinson arrived in York.

That set off a series of actions in Continental Congress, one of which established a National Day of Thanksgiving about 45 days later, on Dec. 18.

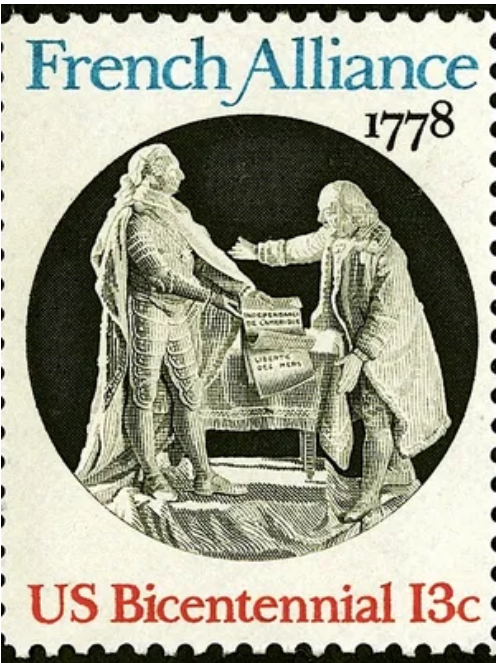

France comes on board

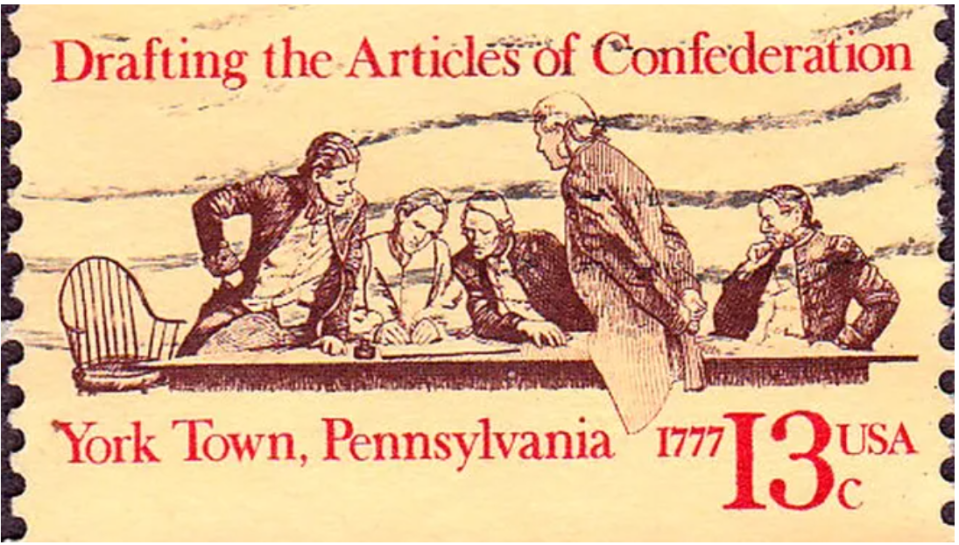

The documents pulled from Wilkinson’s saddlebags meant that the Continental Congress could tell Benjamin Franklin and other diplomats in France that American forces could actually win a major battle. Meanwhile, delegates in York were polishing the fine points of a constitution, the Articles of Confederation, that showed France that the 13 separate states could work as one.

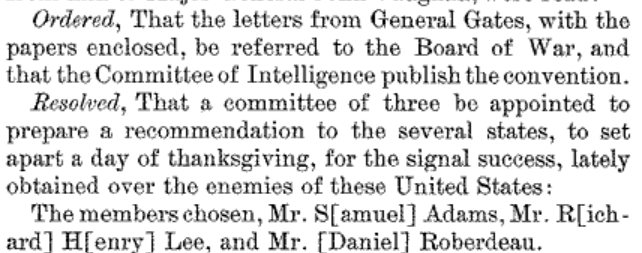

Congress, at ease after Wilkinson’s arrival, created a committee led by Samuel Adams to pen a proclamation of Thanksgiving and Praise. The committee immediately went to work and came back a day later with the finished proclamation. Perhaps the punctual Sam Adams should have been the one dispatched from Saratoga to York to deliver the important papers.

Anyway, Adams began the proclamation: “Forasmuch as it is the indispensable duty of all men to adore the superintending providence of Almighty God to acknowledge with gratitude their obligation to him for benefits received … .”

Henry Laurens, who just succeeded John Hancock as president of the Continental Congress, sent the proclamation of Thanksgiving and Praise to the states with this note:

“The Arms of the United States of America having been blessed in the present Campaign with remarkable Success, Congress, the 18th December next be Set apart to be observed by all Inhabitants throughout these States for a General thanksgiving to Almighty God.”

Thanksgiving as we know it today developed in stages, so it’s a mixed bag among scholars about the first such day.

About 150 years before the York proclamation, the Thanksgiving tradition in America originated with the Pilgrims’ celebration after a full harvest.

In 1676, the Council of Charles, Massachusetts, issued an early Thanksgiving proclamation reflecting a growing custom in New England to annually set aside such days.

Earlier in the Revolutionary War, Congress set aside days for all the colonies to observe “humiliation, fasting and prayer.”

The proclamation in York would be the first of seven such days of Thanksgiving and Praise in the American Revolution, effectively spreading the famed New England custom to all the states.

In 1789, President Washington proclaimed Thursday, Nov. 26, 1789, as a national Thanksgiving Day.

But Thanksgiving did not become an annual event across America until Abraham Lincoln declared in 1863 the last Thursday of November as a national Thanksgiving Day. It has been celebrated annually ever since. Congress changed it in 1941 to the fourth Thursday of November.

Chaplains hard at work

On the national Day of Thanksgiving and Praise — Dec. 18, 1777 — a cold rain fell at the Continental Army’s camp near Whitemarsh.

As directed by Washington’s order, chaplains held services with the officers and soldiers not on indispensable duty.

Later that day, one soldier told of holding a pig roast. Another soldier — one Pvt. Martin — did not savor such morsels.

“(O)ur country, ever mindful of its suffering army,” he wrote, “Opened her sympathizing heart so wide upon this occasion as to give … each and every man a half gill of rice and a tablespoon of vinegar!”

Day of Thanksgiving work

In York, Congress convened at 3 p.m. Dec. 18, though forgoing its morning meeting.

That session, Congress addressed a concern from Pennsylvania officials that Washington might set up his winter camp in Wilmington, Delaware, thereby not giving protection to eastern Pennsylvania from British foraging units and raids.

Laurens wrote a letter to Washington inquiring about the general’s plans.

The commander in chief settled in Valley Forge on Dec. 19, so the issue was decided by the time he received Laurens’ letter.

Washington explained his thinking to Congress but later compared his men camping “under frost and Snow without Cloathes or Blankets” with officials offering criticisms “in a comfortable room by a good fire.”

Courier is scoundrel

Back in York with those surrender documents in hand, Congress deliberated on the customary award for someone who delivered such good news.

Samuel Adams said the young gentleman, Wilkinson, should be gifted with a pair of spurs. But Congress showed the logic customary for politicians. The body promoted Wilkinson from lieutenant colonel to brigadier general.

Washington later prevailed against the conspiracy, if it really was that, to replace Washington with Gates.

According to some reports, Gates turned against Wilkinson in less than six months. After that, Wilkinson was the Forrest Gump of the American Revolution and its aftermath, specializing in schemes and controversies.

Seventy-five years after Wilkinson’s death in 1825, his legacy was such that President Theodore Roosevelt would say: "[I]n all our history, there is no more despicable character."

That said, this scoundrel unwittingly played a role prompting a national Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer.

Sources: James McClure’s “Nine Months in York Town,” National Park Service, Journals of Continental Congress.

Upcoming event

York County History Storytellers will host an evening in which local historians present about “Champs and Foes” in the county’s past. It’s set at 7 p.m. Dec. 7 at Wyndridge Farm near Dallastown. $10/ticket. Details: www.yorkhistorycenter.org/event/history-storytellers.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Courier had places to go so Day of Thanksgiving had to wait in York PA