Cover it? Move it? What experts suggest could address coal ash at Claxton playground

For more than 20 years, the children of Claxton have played on a playground that was built on top of fill material that included coal ash, a waste that has come under scrutiny for possible health impacts.

Knox News spoke to seven scientists who offered suggestions for how the community could keep kids safe, even while the full risks of coal ash are still being studied.

Coal ash is the waste left over from the process of burning coal, which leaves a concentrated cocktail of elements including heavy metals, and potentially elements that emit radiation. Each particle of coal ash can pose a different risk, making it hard to regulate to ensure the safety of communities like Claxton.

Six of the experts said they would want more information and assurance from the government before they would take their own children to play at the Claxton playground. One said they would not take their child to the playground at all.

All seven scientists became more concerned when they learned the playground wasn’t just on top of coal ash but was also in proximity to a coal pile and fly ash disposal site.

How did the playground get built on top of coal ash fill?

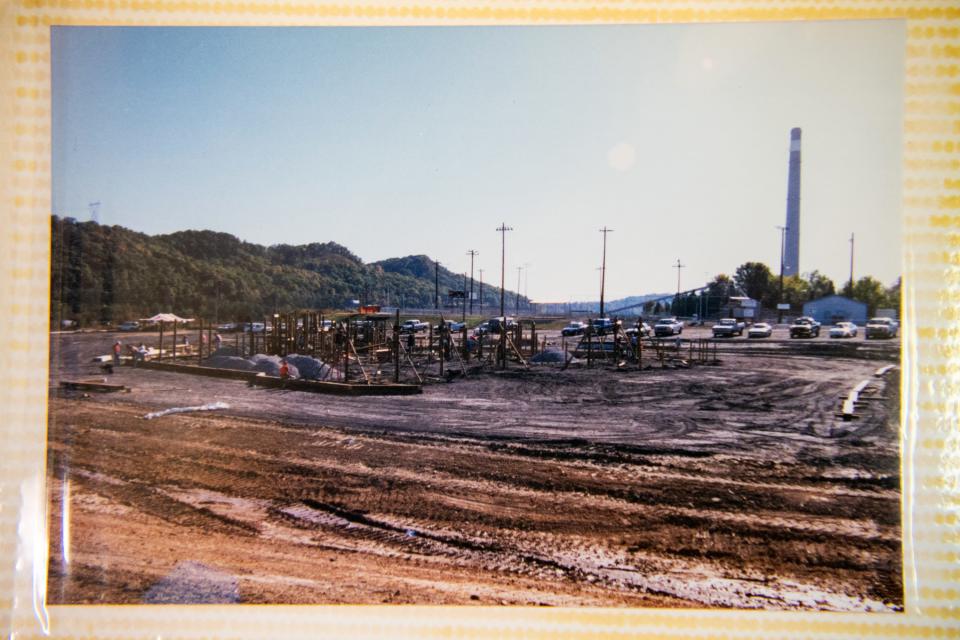

The playground was designed by the students at Claxton Elementary School, and was built in 2000 by the Claxton community with money donated by industries in the area, including Lockheed Martin, UT-Battelle and Bechtel Jacobs.

TVA provided the land and donated fill material to level the terrain on which the playground would sit.

TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks said the project required 11,000 cubic yards of fill material, 30% of which was coal bottom ash, a coarse type of coal ash with a consistency similar to sand and gravel.

The community “provided the remaining materials, including multiple layers of geofibers, gravel and mulch on top,” Brooks said.

TDEC does not have regulatory authority over the site. Instead, Anderson County government has the responsibility to decide how to mitigate any health, safety and financial risks.

In August 2021, Anderson County asked the state to assess whether the playground next to the Bull Run plant was safe. The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation and the Department of Health analyzed soil samples taken from the playground. The two departments produced a report last April.

What did the TDEC and Health Department report say?

TDEC collected soil samples on Dec. 1, 2021, through a contractor. The samples were tested for elements that TDEC associates specifically with identifying coal ash, such as arsenic, lead and mercury. The state produced a report on the findings on April 12, 2022.

Samples from under the swings - where kids’ feet dig into the ground and, over time, expose “deeper soils” below the geofiber layers and mulch - showed “a higher percentage of coal ash than surface soils and contain somewhat higher amounts of metals, metalloids and radionuclides,” the report said.

The report recommended the playground receive “proper maintenance” that would keep the coal ash particles below replaced geofiber and mulch layers, which would “ensure that there is no exposure.” The report also recommended Anderson County plan to inspect the playground regularly, repair damaged areas and add mulch as needed.

With those actions, the report concluded, “There is not a risk of children having harmful health effects from using the park and playground.”

In response, Anderson County plans to mulch the playground annually instead of every other year, as it has in the past, and to conduct routine inspections. The county has put down thick rubber mats under the swings and slides to prevent the kids’ feet from digging into spots on the ground and bringing up soil from underneath.

For subscribers: Coal ash could be reused anywhere. Here's how government does - and doesn't - regulate it

While it might sound all wrapped up, the seven experts below - who have studied coal ash from the perspectives of health, chemistry and geology - say more questions still need to be answered, especially whether this playground is going to stay where it is for the foreseeable future:

Grace Schwartz, assistant professor of chemistry at Wofford College.

Amrika Deonarine, assistant professor of environmental engineering at Texas Tech University.

Laura Ruhl, former assistant professor of environmental geochemistry and hydrology at University of Arkansas, Little Rock.

Alan Lockwood, emeritus professor of neurology at the University of Buffalo and past president of the Physicians for Social Responsibility.

Julia Kravchenko, an assistant professor in the department of surgery at Duke University School of Medicine.

Paul Terry, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Tennessee’s Department of Medicine.

Greg Nichols, a public health expert.

Why airborne particulate matter is a health concern

While the TDEC and health department report outlined different risks that elements in the ash could pose to children, it did not specifically address the risks airborne particles could pose, some of the experts noted.

Particulate matter is just what it sounds like: particles in the air that are small enough to be inhaled.

“Whether they contain toxic elements or not, just fine particulate matter can do a lot. It can cause issues with lungs and breathing,” Deonarine said. “So that's something that I don't think was evaluated in this report, and I think it's important.”

As coal ash is composed of such a variety of elements, any of its particles could contain those metals and potentially elements that emit radiation. The smaller the particle, the more concentrated the composition of the element in the particle.

TDEC’s contracted lab did not report the size of the particles of coal ash it found on the playground, “This information was not reported by the lab and was not a consideration of the sampling plan,” TDEC told Knox News.

Both Lockwood and Ruhl wanted to know the size of the particles found at the playground. The size can impact how easy it would be to inhale or ingest the coal ash particles, which can bring those elements into the lungs and bloodstream.

Fluids like stomach acid and lung fluid can cause the elements in coal ash to dissolve rather than simply passing through the body, Terry and Ruhl said. In order to find out how the coal ash particles would impact the children on the playground, Ruhl said she would have liked to see TDEC test how its samples interacted with those fluids, but those were not part of the report.

When asked, TDEC said, “Standard EPA methodologies were used to prepare the samples for analytical analysis.”

Fly ash versus bottom ash: What’s the difference?

The state’s report also did not address the risks posed by the dry fly ash disposal area located a little over 600 feet behind the playground and the coal pile located a little over 1,000 feet from the playground, on the other side of a baseball field.

When he heard about the proximity of the playground to the coal pile and fly ash disposal, Lockwood said, "It's a terrible idea actually” to have the playground where it is.

That location results in two potential sources of exposure to coal ash for kids playing on the playground:

The bottom ash under the playground, which has the consistency of sand and gravel.

The fly ash and coal pile, which have the potential to release fugitive dust, especially in dry weather.

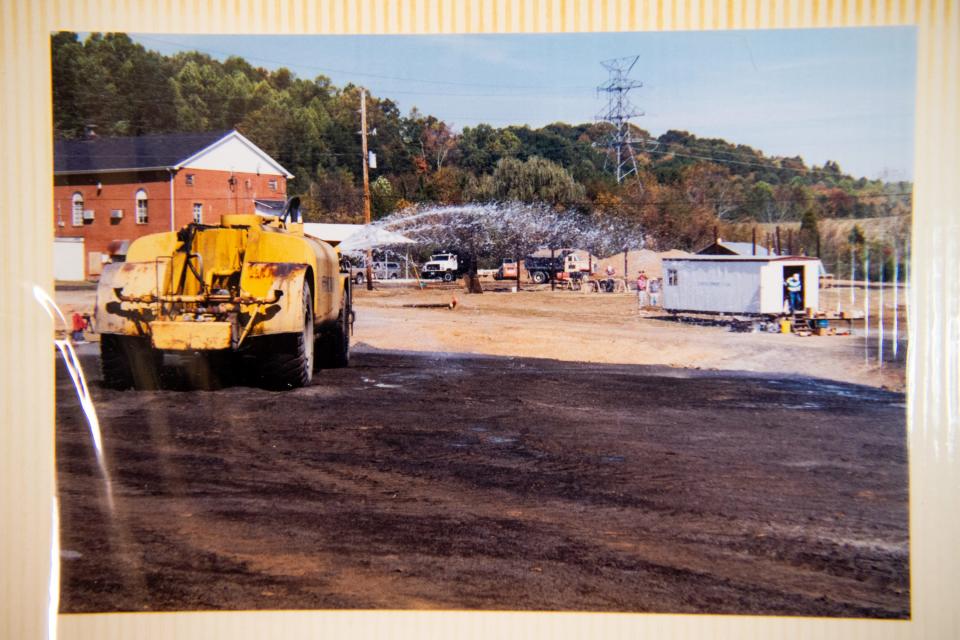

TVA sprays water on both the dry fly ash disposal site and the coal pile to mitigate dust, and has a dust suppression plan at the plant.

TVA has a complaint hotline (844-TVA-DUST) for community members who have concerns. Brooks said “No complaints or concerns have been submitted to the hotline by the public,” though TVA has investigated some cases when community members have voiced concerns by other means.

While TDEC tested the potential for exposure to the bottom ash underneath the playground, it did not conduct air monitoring to test for dust from the fly ash disposal site or coal pile being blown onto the playground.

Five of the experts recommend TDEC conduct air monitoring at the playground to see if the fly ash and coal pile pose a significant risk to the kids’ health.

However, Lockwood, Schwartz and Terry pointed out that air monitoring results still would depend on when and where the monitoring was conducted, what type of monitors were used, weather conditions and wind patterns.

If air monitoring yielded results below limits set by the Environmental Protection Agency but still showed something in the air, Schwartz said it would become a judgment call: how much risk are you willing to take?

Not all kids play the same way

A few of the experts brought up the fact that kids play in different ways. Terry specifically said that when he was a kid he would often play in the dirt at his playground, digging and throwing dirt, even getting into dirt fights.

“I'm ashamed to say it, but we would pick up a big handful of dirt and go up behind somebody who was playing or something and we would dump it on their head,” Terry said. “And it would be in their hair, their eyes, it would be in their mouth and nose. And then they would retaliate, of course. And before long, I was kicked out of the playground.”

In Claxton's case, digging in particular would be a concern because the state told the county to maintain the barriers at the playground, including mulch and geofiber layers, to prevent the coal ash from coming up.

The concern is that a child not only might breathe in the ash but also might ingest it if they put their hands in their mouth after playing on the playground, Ruhl said.

Kravchenko said kids often breathe through their mouths, inhaling large volumes of air unfiltered.

Schwartz suggested putting up signs or making parents aware to keep an eye on how their kids are playing such as making sure they aren’t digging.

“They [TDEC and TDH] assume that kids play in a certain way. And not all kids play in that way. I mean there are some kids out there who are gonna be covered in dirt and if they're covered in dirt that's 10% or higher coal ash, I'd say that's not good,” Terry said.

It’s hard to assess risk when it comes to coal ash

Everything we do in life comes with a risk, from using cleaning products to driving a car, but judging those risks is helped by years of studies and learning from past mistakes. With this playground and coal ash, however, the science can’t tell us yet how dangerous it is, Schwartz, Terry and Nichols said.

“We just don't have enough data. We just haven't studied it enough,” Nichols said.

Not all coal ash is the same. The composition of coal ash can vary from where the coal was mined, how it was burned and how the ash was processed before disposal.

As a result, creating regulations for coal ash is complicated because the risk factors can vary. One area of coal ash could be high in arsenic while another might not, in addition to any difference in size of coal ash particles.

Terry said that if you look at the individual elements that can be found in coal ash, each of them poses its own risk. When they’re combined the total risk is likely greater than exposure to the sum of the individual elements on their own.

Right now, science can’t tell us how dangerous coal ash is. But at one point, it couldn’t tell us about the dangers of asbestos, Terry pointed out. We're on the edge of realizing that coal ash is likely more dangerous than we think, he said.

One of the biggest examples we have of what coal ash exposure can do to people is from the lawsuits by former workers who cleaned up the Kingston coal ash spill, Schwartz said. A 2018 verdict in the cases linked the ash at the spill site and the working conditions to about 10 different health conditions and diseases that the workers experienced since the cleanup.

But the workers’ exposure is not the same as children playing on the Claxton playground. The Kingston workers experienced an occupational exposure to the ash, breathing it in for long periods of time while working at the spill site.

The kids at the playground, on the other hand, might be experiencing lower doses of the ash but over a longer period of time depending on how they are playing, how often they go to the playground, the climate at the playground and other factors.

“It's likely not something that's an acute risk, right? You're [not] going to go to this playground one time and be poisoned or something, but there's something to be concerned about the cumulative risk over time of years and years and years, and what that does to you,” Schwartz said.

For Kravchenko, the report from last year isn’t enough to assure the location is safe specifically for kids, who are the most vulnerable to environmental health impacts because their systems and bodies are just developing, which could lead to health problems down the road.

“That means further increased risk of many, many diseases like diabetes, arterial hypertension, asthma and many, many neurological disorders, many, many others that could appear like 10, 20 or even 30 years later,” Kravchenko said.

Kids who have preexisting conditions, such as asthma or diabetes, might be even more at risk of negative impacts when exposed to coal ash, Terry said.

Should the Claxton playground be moved?

One way to eliminate both the risk of the bottom ash underneath the playground and the fly ash disposal site next door would be for the playground to move, which might be the best option, the seven experts said.

“In lieu of greater certainty it’s the most prudent thing to do,” Terry said.

“I don't think that it's reasonable to keep this playground here,” Kravchenko said. “I think it's reasonable [to] try to find another place and organize it from the very beginning, first, with as clean as possible in this area.”

What can be done if the playground stays where it is?

The Claxton playground has been there for more than 20 years. If it’s going to stay where it is for the next 20 years, the community will need to consider how to protect the kids.

“But now there's a lot of questions about how to move ahead. And I think it's important that the community continue to be involved,” Nichols said.

At least five of the experts said that the county should continue to keep a maintenance plan, as it now does. Schwartz and Lockwood suggested that the more barriers the community can place between the ash and the children, the better.

Schwartz suggested the community could remove the coal ash from underneath the playground and replace it with new soil, potentially adding gravel.

Deonarine and Nichols suggested maybe capping off the coal ash, a practice that is done commonly on contaminated land or land where coal ash is disposed of. Caps can contain a certain number of liners and soil, basically creating more barriers. Nichols suggested a concrete cap could be installed.

With respect to the partially open fly ash pile and coal pile next door, Lockwood suggested the two should be removed or at least covered. TVA plans to remove what’s left of the coal pile after the Bull Run Fossil Plant retires, which is set to happen by December 2023.

The fly ash disposal site is part of TDEC’s investigation of the coal ash at all of TVA’s plants, which could require TVA to remove the coal ash at Bull Run, but there has not been a decision yet.

In the interim, the same dust control measures that are in place now would still apply, Brooks said.

Deonarine, Ruhl and Schwartz would like to see continuous periodic testing of both air and soil. Schwartz specifically suggested testing annually for the next five years. Terry agreed that more testing could help to better understand exposure potential.

All of these suggestions would cost money, a point the experts acknowledged especially when discussing the topic of more testing and monitoring. Testing cost TDEC about $66,054.23 from August 2021 to the end of May 2022.

“This cost included planning, sampling, laboratory analysis, report development and review activities. Funds came from TDEC’s Bureau of Environment, not a standalone grant. This figure does not include any potential expenses that the Tennessee Department of Health may have also incurred,” TDEC said in an email to Knox News.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Scientists suggest ways to deal with coal ash at Claxton's playground