How COVID-19 Is Impacting the First Scheduled Federal Execution of a Woman in Nearly 70 Years

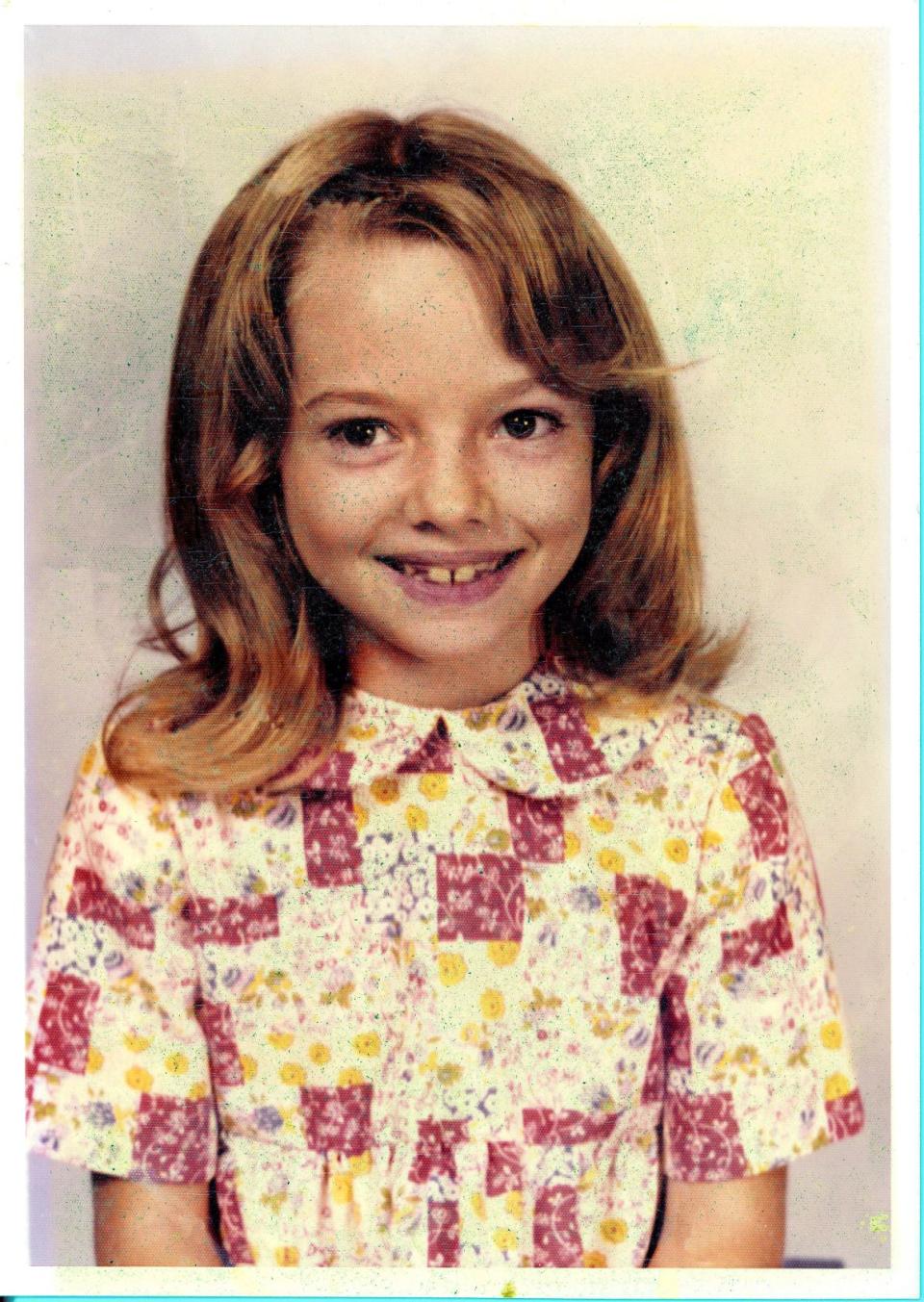

A photograph of Lisa Montgomery—the only woman on federal death row—taken in prison. Credit - Courtesy photo—Attorneys for Lisa Montgomery

Lisa Montgomery could be the first woman executed by the federal government in 67 years.

Montgomery, 52, has been the only woman on federal death row since 2008 after a Missouri jury found her guilty of federal kidnapping resulting in death and recommended the death penalty.

Since a date for her execution was first announced on Oct. 16, over 1,000 advocates have signed letters urging President Donald Trump to commute Montgomery’s death sentence to life without parole, pointing to her diagnoses of serious mental illnesses, which stem from a history of abuses that advocates argue are inextricable from her crime.

All of Montgomery’s prior attempts at appealing her sentencing have been rejected, so clemency—the process by which a governor, president or administrative board uses their executive power to reduce a defendant’s sentence—is her only legal recourse available.

“Readers often confuse clemency with pardon in death penalty cases,” says Sandra Babcock, a clinical professor of law at Cornell Law School and faculty director of the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide, who is working to delay Montgomery’s execution so her lawyers can present a clemency petition. “[We are not asking] that she be absolved of guilt. What we’re asking is that she be extended mercy.”

Beyond being decried by advocates, the execution is mired in legal controversy. Montgomery’s execution was originally scheduled for Dec. 8, but has been enjoined by a judge until Dec. 31 after her longtime lawyers became ill with COVID-19, which a recent lawsuit alleges they contracted while traveling to visit her in prison. A lawsuit filed by the ACLU on Nov. 6 also alleges that Montgomery is currently being held in conditions that “amount to torture,” and demands an end to them.

The Department of Justice, the Bureau of Prisons and the two prisons named in the suit did not respond to TIME’s request for comment.

Here’s what to know about the case of Lisa Montgomery.

She’d be the first woman in 67 years to be executed by the federal government

The Trump administration announced it would resume federal executions after a 17-year hiatus this summer. Since then, the federal government has executed seven people, and scheduled three more executions to take place in the final weeks before Trump leaves office (including Montgomery’s.) For comparison, three people were executed by the federal government in the entire 2000s.

If the final three scheduled executions are carried out this winter, they will be the first executions under a “lame duck” president in over 100 years. President-elect Joe Biden has said he intends to end the use of capital punishment by the federal government while in office.

Read more: The Death of the Death Penalty

But every person killed so far this year in what advocates argue is a “spree” of federal executions has been a man. All the protocols released by the federal government on how executions should be handled use male pronouns, and refer to male grooming and detailed steps that must be taken at the all-male Federal Correctional Complex in Terre Haute, Ind., which houses the majority of the federal death row, Stubbs says.

“We haven’t seen protocols around women,” Stubbs says. “We haven’t seen a federal execution of a woman in 67 years. There is no precedent.”

Anti-gender violence advocates object to her execution

Gender also plays a central role in the facts of Montgomery’s case, advocates argue.

“Understanding her crime requires us to understand the trauma that she experienced,” says Leigh Goodmark, a professor of law at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law and the director of its Gender Violence Clinic. “They are inextricable from each other.”

Goodmark is one of 800 gender violence scholars, survivors, advocacy organizations and law clinics signing on to a Nov. 11 letter urging President Trump to commute Montgomery’s death sentence to life without parole.

The letter notes that Montgomery was born with brain damage as the result of her mother drinking while she was in utero, and was from a young age the victim of child-trafficking, rape, incest and domestic violence. She was pushed into marrying her step brother at the age of 18 and had four children before being sterilized against her will, the letter continues. As a result, she developed dissociative disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder.

“To have the kind of cumulative experiences of violence that Lisa had is unimaginable—except that it happened,” says Goodmark. “There’s no time in her life prior to the crime when Lisa Montgomery is not being subjected to some form of abuse.”

In 2004, Montgomery told her second husband that she was pregnant, despite having undergone a sterilization procedure, per court documents. That December she contacted 23-year-old Bobbie Jo Stinnett, who was eight months pregnant, killed her and kidnapped her unborn baby, who survived, according to the Department of Justice. Per court documents, Montgomery initially told her husband the baby was hers, but confessed to the crime shortly after.

“A history of being victimized is not an ‘abuse excuse’ as the jury was told at her trial,” a letter also sent to President Trump signed by 41 current and former prosecutors, reads. “We view this kind of evidence as critically relevant to determining the appropriate punishment for a serious crime.”

(In addition to the letter from prosecutors and anti-gender violence advocates, 100 organizations and individuals that work to stop human trafficking have sent their own letter to Trump, as have 40 child advocates, 80 formerly incarcerated people and three major mental health advocate organizations.)

“Lisa has taken full responsibility for her actions and expressed profound remorse for her crime,” the prosecutors’ letter continues. “We are persuaded that in light of all these factors, granting Lisa clemency will not only serve the interests of justice, it will further them.”

A judge delayed the execution because her lawyers contracted COVID-19

Montgomery’s execution was originally scheduled for Dec. 8, but a federal judge temporarily enjoined the execution on Nov. 19 after a lawsuit filed by Babcock’s Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide asked for an extension because Montgomery’s longtime lawyers are sick with COVID-19—which the suit alleges they contracted while traveling to visit Montgomery in prison—and are experiencing “debilitating” symptoms.

“Mrs. Montgomery’s lawyers cannot represent her because they are seriously ill, through no fault of their own,” the motion argued. “On the contrary, they are sick because [Attorney General] Barr recklessly scheduled Mrs. Montgomery’s execution in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.” In response, District Judge Randolph Moss ruled that the federal government cannot execute Montgomery until Dec. 31, giving her legal team more time to complete her clemency application. It is unclear if the federal government will attempt to appeal the ruling.

“[The] public’s interest in seeing justice done lies not only in carrying out the sentence imposed years ago but also in the lawful process leading to possible execution,” Moss wrote in his opinion.

Clemency is the process in which a defendant appeals to a governor, president or administrative board to pardon or reduce their sentence, after all appeals have been exhausted. The reasons can range from concerns about a defendant being wrongly convicted, a co-defendant receiving a lesser sentence, or concerns about a defendant’s mental illnesses, per the non-profit the Death Penalty Information Center. While rare, clemency has been granted in past death penalty cases; in January, the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles granted defendant Jimmy Meders clemency just hours before his scheduled execution.

“In a death penalty case, clemency is everything,” explains Babcock. “It is the one chance that lawyers have to put everything before a decision maker and to say, you know, ‘look at the person’s entire life.”

Read more: Here’s Why Death Penalty Opponents Say Resuming Federal Executions Is the Wrong Move

So when Montgomery’s attorneys were told her clemency application was due on Nov. 15, just 30 days after her execution was scheduled, they went to visit her where she’s currently imprisoned—Federal Medical Center, Carswell in Texas, which has reportedly recently experienced a COVID-19 outbreak.

Montgomery’s attorneys visited her on Oct. 19, Oct. 26 and Nov. 2, per Babcock’s lawsuit. They began experiencing COVID-19 symptoms on Nov. 5 and tested positive shortly afterwards, Babcock says.

Many advocates argue that carrying out executions amid the COVID-19 pandemic is dangerous. In September, the ACLU released a report based on Bureau of Prison data that they argue shows that the federal executions over the summer likely caused a spike in COVID-19 numbers. On Nov. 17, the Congressional Black Caucus called for Barr to put a stay on all upcoming executions for this very reason, arguing that spikes in COVID-19 infringe upon defendants’ constitutional rights to have “every available legal recourse in the days before their execution.”

The ACLU filed a lawsuit over the “torturous” conditions she’s being held in

A separate suit was also filed by the ACLU on Nov. 6 in response to the conditions Montgomery is allegedly being held under. When her execution was scheduled, the suit alleges that Montgomery was stripped of all her belongings, moved to a cell with 24/7 bright light and put under 24/7 surveillance by guards, including male guards, and including when she uses the bathroom. She was only given a “loose-fitting gown with Velcro straps” to wear, the suit continues, and allegedly was only provided underwear after “some days and numerous requests;” The suit also alleges that, after guards gave her underwear, they told her to “be a good girl, now.”

“Our experts say that this is directly reminiscent of the kind of control [and] the kind of language that her abusers used,” says Cassandra Stubbs, director of the ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project, whose suit argues the conditions “amount to torture” given Montgomery’s history of gender-based violence.

The suit—which was filed against Attorney General Barr, the federal Bureau of Prisons, the Federal Medical Center Carswell and the wardens of the Federal Correctional Complex, Terre Haute, where Montgomery is scheduled to be executed—asks for an end to those conditions, arguing they’re “fair harsher” than what men are subjected to. Babcock also tells TIME that Montgomery has been “deteriorating by the minute since she learned about her execution date,” but mental health experts cannot get in to see her given the ongoing pandemic.

The ACLU’s suit also requests that Montgomery not be transferred to the all-male Terre Haute prison for her execution, pointing out that she breaks out in hives “when in the presence of men, particularly strangers.”

And all these conditions are “exacerbating” her underlying mental health conditions and making it more likely that she’s going to “dissociate and lose touch with reality,” Stubbs adds. “This is inhumane treatment.”

Advocates likewise maintain that Montgomery does not match the “worst of the worst” profile that the death penalty is supposedly reserved for.

In an essay published Nov. 19 in Newsweek, her sister, Diane Mattingly, stressed this point, urging President Trump to commute Montgomery’s sentence. “[The] federal government plans to execute her for a crime she committed in the grip of severe mental illness after a lifetime of living hell,” Mattingly wrote. “She does not deserve to die.”