COVID-19 ‘vaccine hesitancy’ has scientists concerned about new survey results

Scientists are expressing concern over what they call “vaccine hesitancy” regarding the COVID-19 pandemic.

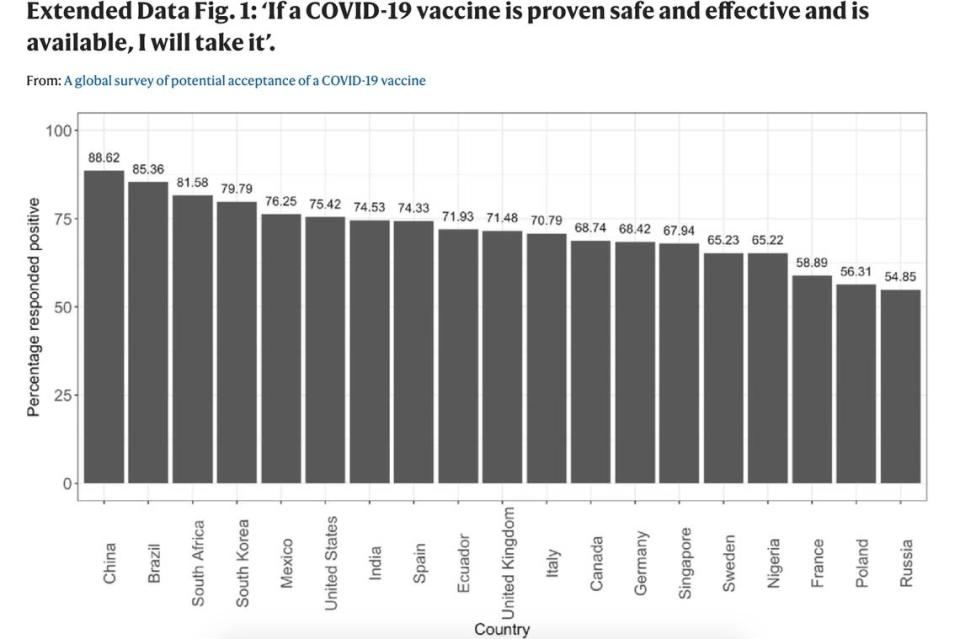

A survey of more than 13,000 people in 19 different countries most affected by the coronavirus found that about 72% of people said they are very or somewhat likely to get a vaccine when one proves safe and effective.

Although that’s over half, the group of international experts says the current levels of willingness are “insufficient to meet requirements for community immunity.”

Part of the blame goes to anti-vaccination activists who have been campaigning in several countries, as well as those who deny COVID-19’s existence altogether. But the survey showed a strong connection between trust in one’s government and trust in a vaccine, with those in Asian and middle-income countries showing greater acceptance.

And regardless of nationality, all respondents said they would be less likely to accept a coronavirus vaccine if their employers required them to get it. The findings, published Tuesday in the journal Nature Medicine, also reveal patterns involving age, income, education and history of coronavirus infection.

“The far-from-universal willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine is a cause for concern,” the scientists wrote in their study. “Unless and until the origins of such wide variation in willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine is better understood and addressed, differences in vaccine coverage between countries could potentially delay global control of the pandemic and the ensuing societal and economic recovery.”

The survey was conducted in June of 13,426 people in 19 countries from among the 35 hardest-hit regions in terms of cases per million people, including Brazil, Canada, China, Poland, Nigeria, South Korea, Spain, Singapore, Russia, the U.K. and the U.S.

Researchers wanted to capture what the World Health Organization coined in 2015 “vaccine hesitancy” — “a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services” — for the current pandemic. The WHO even identified it as one of the top 10 global health threats in 2019.

Trust in government made biggest impact on vaccine willingness

People in China who completed the survey gave the highest proportion of positive responses (89%) to questions asking if they will take a COVID-19 vaccine, while Russians gave the lowest proportion (55%).

About 75% of respondents from the U.S. said they will take it if proven safe.

This correlates with greater trust in central governments, the researchers said, such as those in China, South Korea and Singapore. People in middle-income countries such as Brazil, India and South Africa were also more willing than others to accept a vaccine.

The trend continued for other questions that explored demographics and employment.

About 32% reported they would accept their employer’s recommendation to take a coronavirus vaccine and about 18% said they would somewhat or completely disagree, with the most positive responses coming from China.

The researchers say requiring employees to get the vaccine “could fail if it is perceived as limiting employees’ freedom of choice or a manifestation of employers’ self-interest. ... A careful balance is required between educating the public about the necessity for universal vaccine coverage and avoiding any suggestion of coercion,” the study reads.

Will you need two COVID-19 shots? Many vaccines require multiple doses. Here’s why

In general, older people were more likely to say they would take a vaccine, while younger individuals were more likely to accept an employer’s vaccine recommendation.

Those with higher incomes, higher levels of education and those living in regions with “medium and high” levels of COVID-19 cases and mortality answered more positively toward getting a vaccine than others.

Women were also more likely to answer “yes” to getting vaccinated.

At the same time, people who said they had been infected with the coronavirus, or had a family member who got sick, “were no more likely to respond positively to the vaccine question than other respondents.”

“These data could help governments, policymakers, health professionals and international organizations to more effectively target messaging around COVID-19 vaccination programs,” the scientists said in their study.

‘Addressing vaccine hesitancy requires more than building trust’

The researchers say “clear and consistent communication by government officials is crucial to building public confidence in vaccine programs.”

It can be done by explaining how vaccines work, how they are developed and what the process that determines their safety and efficacy looks like.

As well, communication should address community-specific concerns or misconceptions, be sensitive to religious beliefs and confront historic issues that have given rise to distrust in vaccines.