On COVID-19 vaccine, ‘get as many shots in arms as possible, right away’: ex-FDA chief Q&A

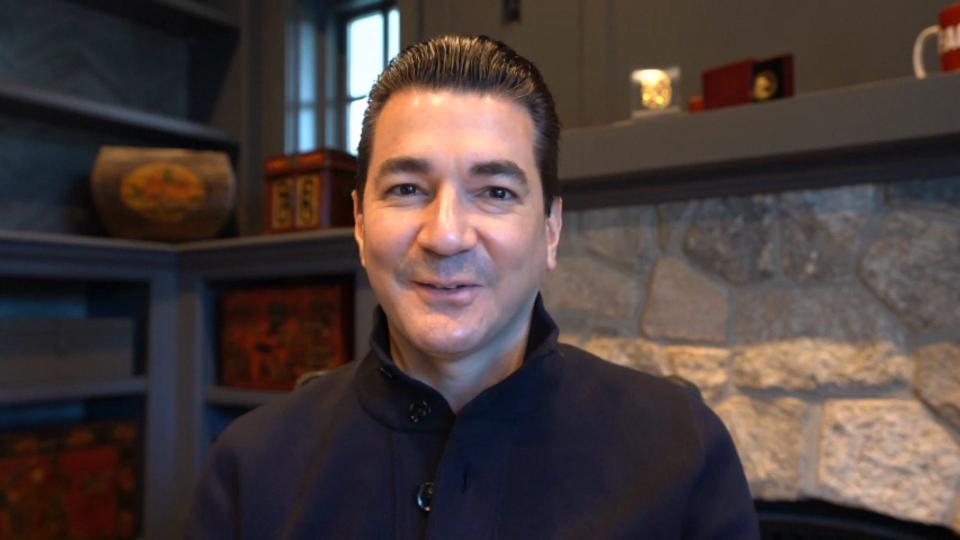

With the latest coronavirus wave producing record numbers of cases, hospitalizations and deaths across the United States, the USA TODAY Editorial Board spoke Monday with Dr. Scott Gottlieb, former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration. Gottlieb, 48, serves on the board of Pfizer, which is asking the FDA to authorize the company’s vaccine for emergency use. Questions and answers have been edited for length, clarity and flow:

Q: Even as the Pfizer vaccine could be approved as early as Thursday, we're in the midst of the worst surge yet of the coronavirus. How bad is this going to get before it gets better?

A: I think it's going to get a lot worse before things start to improve. The hardest four to six weeks are ahead of us. I think we're going to see daily new infections continue to increase for the next four weeks. And then we won't hit peak hospitalizations until probably six weeks, maybe mid-January. We could see upwards of 150,000 to 175,000 people hospitalized when we hit the peak and maybe upwards of 40,000 to 50,000 people in the ICU. That's going to really press the health care system.

Q. What about deaths?

A. By the end of this year, we'll probably be at around 300,000 Americans who have lost their lives as a result of COVID, and toward the end of January it could be around 400,000. So the most difficult period of this pandemic is ahead of us (before) things will get better. This is really, I think, the last surge of infection. That doesn’t mean coronavirus is going to go away altogether.

Q: Walk us through what you think 2021 might look like in terms of vaccine rollout and some sort of return to normalcy.

A: I'm optimistic about 2021. There's some disagreement about how quickly things will get better. I think things will get better very quickly, in part because probably 100 million Americans will have been infected by the end of January and in part because we're going to start rolling out a vaccine that seems to be very effective, based on the initial clinical studies.

Q. When should we start to see improvement?

A. As we get into probably February and certainly into March, I think you're likely to see the virus largely collapse. And I think that we're going to enter a period, over the spring and the summer, when it's going to be relatively quiescent. We'll see cases get reported, but we're not going to see major spread. There'll be sporadic outbreaks. I fully expect kids will be back in summer camp and people will be having barbecues again outdoors.

Q: What about the rest of 2021?

A: As we head into the fall, we face renewed risk that there's going to be outbreaks. But at that point, hopefully there's vaccines that are widely available. We'll be vaccinating the population for this before the fall COVID season. And we'll go into the winter with a population that's largely protected and has immunity. And so, while it will spread, it will spread far less.

Q: When do you see a return to large events like concerts, weddings and sports with fans in the stands?

A: If you have a vaccine that's effective and widely deployed, and a virus that has circulated through the population, I think we'll return to gatherings and indoor gatherings next year. There's going to be some precautions taken, and I don't think that we're going to do things next year like we did in 2018. Customs are going to change a little bit. I think you're going to see masks more generally worn in airports and public transportation, and it's not going to be something that's objectified or looked upon strangely.

Q. Could continuing certain precautions have other benefits?

A. Remember, these mitigation steps — the social distancing, the mask wearing, all of the things we're doing — were really designed as a way to stop a flu pandemic. They weren't designed with coronavirus in mind. They seem to be much more effective at breaking chains of transmission of flu than even breaking chains of transmission of COVID. So whatever we do to try to mitigate the risk of COVID, we're probably going to see in terms of sharply decreased rates of flu. That’s going to have a very direct payoff in terms of not just improved health, but also productivity gains.

Q. Once vaccines are approved, what does the rollout look like?

A. It's very clear that the first people to get it are going to be health care workers and elderly people who live in congregate settings, such as nursing homes and long-term care facilities. Then there's some debate about what the next tranche of eligible people is going to be. This is going to feel to most Americans like a difficult process. For a time, demand is clearly going to outstrip supply.

Q. How long does that period last?

A. I think we're going to see an inflection point here at some point in the spring where, all of a sudden, a commodity that was very scarce and hard to get is going to become much more plentiful. I don't know where that inflection point is, when supply is suddenly going to really come online. But my guess is it's going to be sometime around March that we're going to see a lot more vaccine in the market. What seemed like a scarce commodity that was being very tightly rationed will suddenly become more generally available to most Americans.

Q: There's worldwide demand for the vaccine. How does Pfizer decide how much to give the United States, the United Kingdom and the other countries that are clamoring for it?

A: Well, it’s largely 50-50. Pfizer's production is split across two facilities, one in Europe and one in the United States. When the company said we'll have 50 million doses available in December — 25 million for the U.S. and 25 million for the non-U.S. markets — most of those doses have already been manufactured and are ready to go. So there shouldn't be any issue with getting that supply available for December.

Q: Why was the U.K. able to roll out the vaccine faster than the U.S.?

A: They deployed the vaccine quickly once the authorization was given. We're going to deploy the vaccine quickly once an authorization is given here in the U.S. So I don't think there's any difference there. The difference was that they authorized it before we did. But we made deliberate decisions about our regulatory process for understandable reasons, for prudent reasons, that ultimately delayed the authorization of this vaccine by a matter of (two, maybe three) weeks.

Q. If the FDA grants the emergency use authorization, how long will it be until vaccines are administered?

A. When the United Kingdom authorized the vaccine last week, there were trucks, Pfizer trucks, rolling into the United Kingdom through the Chunnel, delivering supplies into the U.K. And so those vaccines are prepositioned right now. The U.K. said they're going to start to vaccinate as early as (Tuesday) and may vaccinate upwards of 800,000 people this week. And the same thing is going to happen in the U.S. as soon as the company gets the authorization from the government that this vaccine is authorized to be made available. It will be shipped immediately to locations that have already been predetermined as vaccine distribution points. And so, it will be immediately available.

Q: For the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, each person is supposed to get two doses, three or four weeks apart. Between the two companies, 40 million doses are expected to be available in the U.S. this month. Is it better to give 20 million people two doses, one in December and one in January, or get all 40 million out there and then catch up to the second dose as supply increases?

A: I feel very strongly that we should get as many shots in arms as possible, right away. The reality is that one dose is partially protective. I just fundamentally disagree with (saving half the supply for January) because, the reality is, supply reacts very quickly in 2021. If something happened and we didn't have supply available in 2021 to give everyone who got the first dose in December their second dose, we're going to, quite frankly, have bigger issues. It's going to mean that there was something that went wrong with manufacturing, and we're not going to have enough supply for January and February and perhaps March. So I don't think we should be holding on to supply now, anticipating that something goes wrong that's going to cause a lot of other challenges.

Q. Isn’t that a gamble?

A. We should be taking some risk. This is an environment where there is a widespread pandemic causing immediate death and disease. This is the type of environment where you take some risk and try to get as many doses out as possible in December, recognizing that this is going to be over in a couple of months. What we do right now is going to determine how many lives we can save. Holding on to a shot now — so we can give it by the end of January when this epidemic across the U.S. has largely run its course and is starting to decline — that fundamentally doesn't make a lot of sense to me.

Q: Who ultimately will make that decision?

A: Well, it's going to be Health and Human Services and Moncef (Slaoui), who's head of Operation Warp Speed, and some of the logistics people who are managing that. They seem to be heading in the direction of making the decision that they're going to hold on to some supply and not deploy all the vaccines in December. I think it would be a shame to have stockpiled vaccine in December so you can have it on the shelf at the end of January, right as this epidemic has run its course and we're starting to see declines in the number of daily new cases.

Q. What makes you think that will happen?

A. We've seen these epidemic curves before. They are sharp up and they're a sharp trip down. At some point in January, this virus is going to start to decline very rapidly. And if we've stockpiled vaccines that we could have given to people who could have benefited from that in December, so that we could have it sitting on the shelf right at the time that the virus is declining, I don't see us maximizing the public health utility of this product that way.

Q: When does this decision have to be made?

A: This is a decision that is going to get made and play out over the month of December. This is a question of how many people do we get vaccinated in December. I think this is really borne of probably some hesitation that they don't have full visibility into the manufacturing supply chain. Look, I don't have any more visibility than they do. They probably have more proximity to it than I do, notwithstanding the fact that I'm on the board of Pfizer. But No. 1, I have confidence that things will go well. And No. 2, I think in a circumstance like this, you need to have that confidence. You need to take a little bit of risk and hope things go well, because if things don't go well, like I said, we're going to have bigger problems. It's not just going to be that we can't get everyone a second dose on time. It's going to be we can't get anyone new a first dose. And so, we need to kind of hope for the best and take a little bit of risk that things will work out well.

Q. How can you influence the decision?

A. I don't have any way to influence this other than speaking out publicly. I think it is a fundamental mistake to take a vaccine and put it in a warehouse somewhere on a shelf when people could potentially be benefiting from it right now. We have a very acute period where we're going to see a lot of death and disease. And they've said as much. They said the next six weeks are going to be the hardest period in the history of America. So during the hardest period in the history of America, you're going to take some vaccine that could potentially be better for some people and lock it in a drawer? Fundamentally, that doesn't make sense to me.

Q. How many people ultimately need to be vaccinated?

A. If you have a vaccine that continues to demonstrate the profile that these vaccines have shown, that's widely accessible and largely used, you don't need to vaccinate 80% of the public. I mean, if you get to 50%, that's going to be a pretty effective target. Anything above that, I think is just sort of additional benefit.

Q: When would we know whether that’s going to be enough?

A: Partly it's going to depend on what we learn about the vaccine. Does the vaccine just prevent signs and symptoms of COVID, or is it actually preventing infection? Is it reducing someone's likelihood of spreading the infection? Depending on what the answers are, that's going to influence how many people you need to vaccinate in order to achieve a level of immunity that really stops the circulation of the virus.

Q. What should Pfizer and the FDA be doing right now to build public trust in vaccines?

A. In terms of how to inspire public confidence, I think that we need to be doing everything we can to collect data about the safety profile of these vaccines and also answer these questions about the true benefit. Are they preventing infection? Are they preventing viral shedding?

Q. What else?

A. It is going to be important to get some people to vaccinate themselves publicly, to assure the public of their confidence in the vaccine. I know former presidents have talked about getting vaccinated in public. Find a few celebrities and a few influencers, people who other individuals trust. Get them vaccinated early, get them vaccinated on TV. I used to always get my flu vaccine on TV every year. I felt it was important that the FDA commissioner get vaccinated publicly for flu. So people saw me getting vaccinated and saw me expressing my confidence in the vaccine. We're going to need to do things like that with this vaccine.

Q. Won’t people complain if celebrities seem to be jumping the line?

A. I think the public interest is very well served if we could find some people who are willing to step out and make a public statement and vaccinate themselves regardless of where they fall in the queue. And I would put the former presidents at the top of the list, and probably some other social media influencers and celebrities.

Q: Is it going to be a big problem to deploy the vaccines, particularly when you think about the storage and the extremely low temperatures that are needed?

A: I don't think that the actual mechanics of the distribution is going to be the challenge. I think the bigger challenge is going to be, as long as we're in this rationing phase, trying to apportion it equitably. If we make decisions about which group should be eligible, making sure we can actually find those individuals and verify their "eligibility." The logistics of storing (the vaccine), creating the injection sites, I think that's largely been worked out. Nothing goes completely smoothly, but there's been a lot of thought put into this.

Q: Are you worried about the virus mutating each year like the flu? Will we need a new version of the vaccine next winter?

A: I'm not that worried about it. This virus is going to drift, and there are going to be mutations. But the idea that you're going to see a very rapid mutation, one that becomes the predominant form within one season and would just obviate the vaccine, is unlikely. That doesn't mean that you wouldn't be reformulating the vaccine every two or three years (based on) how the virus itself has evolved over time. You probably will, but that should be a relatively straightforward process. So I'm not worried about waking up one day and finding, all of a sudden, the vaccines don't work anymore.

Q: Did this outbreak in the U.S. unfold in an even worse way than you anticipated?

A: I think it's extending longer. The peak is going to be larger than we anticipated, in large part because we haven't taken any real policy response. When you think about these kinds of epidemics, you always expect there to be a compensatory change in behavior and policy. As things get worse, people start to stay home or they wear masks more. Businesses take more precautions. Policymakers step in. I think that the sort of response to this has been much slower than I would have anticipated.

Q. What else was surprising?

A. The other part of this that I think was unanticipated was the big wave of infection in the summer. What many of us didn't necessarily see was that in the South, people would be going indoors to get the benefit of air conditioning in the summertime and going into congregate settings, into high-risk settings, and that you would see that big wave of infection that swept Texas and Arizona and Florida. So we never really had a period where there wasn't a lot of infection somewhere in the United States. That set us up for a much more dangerous fall where the country was already heavily seeded. Then you had (the big motorcycle rally in Sturgis, South Dakota), which was a superspreading event. And so the Midwest got very heavily seeded. Now you have sort of infection everywhere. It's really a confluent epidemic across the whole United States.

Q: Do we have a two-tier medical system where some patients have better access to treatments, such as monoclonal antibodies, than others?

A: The antibodies are definitely being rationed right now, and they're not widely accessible. Where you present for care and how aggressive your physician is in advocating for you is going to probably impact on the margins of your ability to get access to those drugs, unfortunately. There is, I think, an element of truthfulness in the fact that, where you go, who your doctor is, how strongly they advocate for you is going to have some impact on your ability to get access to these scarce antibodies, at least over the next couple of months while they're still in short supply. There'll be ample supply at some point in 2021.

Q. Did it have to be this way?

A. These didn't need to be in short supply. Many of us, including myself, were writing and advocating back in April and May that we should start trying to requisition biologics manufacturing capacity, recognizing that the antibodies were going to be available at some point in the fall. They were the most likely therapeutics to be available that would have an impact on the disease. This was a foreseeable problem. There's things we could still do now to try to increase manufacturing capacity, have more of these drugs heading into next year. We just didn't do it.

Q. What happened?

A. The companies themselves went through a lot of steps, really extraordinary steps, to increase their manufacturing capacity. Regeneron literally moved products that they manufactured in the U.S. out of the U.S. to free up domestic manufacturing capacity just to make these antibody drugs. But, ultimately, we needed to have the government step in and try to pay some companies probably to turn over their manufacturing capacity for other drugs to the U.S. government to manufacture these antibodies and also potentially build new facilities.

Q. How long would that have taken?

A. Building a biologic facility would typically take two years. If you really crash it, maybe you can get it done in a year. (If we) started this right at the outset in March or April, there's a chance we could have had some facilities coming online right now, if we really would have put a concerted effort into doing this and it would have made a difference. So these didn't need to be in short supply. I think we need to rethink in the future how we approach these kinds of problems, because there's things we could have done here.

Q: There still seems to be a lot of confusion about airborne transmission of the virus versus surface transmission from things like packages or serving utensils or doorknobs.

A: As far as touching a contaminated surface and getting a virus, that seems to be far less of a risk than we initially thought. That doesn't mean it's not a risk. You can still get the virus through touching contaminated surfaces and then rubbing your eyes. So good hand hygiene is still something that's simple and prudent. But it seems that most of the spread, and maybe the vast majority, is through droplet transmission and maybe some aerosolization of the virus.

Q: President-elect Joe Biden plans to nominate former congressman Xavier Becerra for HHS secretary. Under the circumstances, should he have picked someone with more of a public health and science background?

A: I don't really have an opinion, to be perfectly frank. I don't know the congressman other than by reputation. Above all else, HHS is really a management challenge. It's a political job. It's a management job. And so I think having someone with a pedigree where they have political experience, where they have management experience, probably are the two most important variables. Public health experience is certainly important, being able to speak the language, but a lot of people who don't have a clinical background or don't come out of a deep public health background can speak the language.

Q: Would you be interested in serving in the Biden administration?

A: I’ve had a couple of discussions with the transition team just to give them some advice. They've reached out to me. I've not had any discussions with the administration about any role. I've tried to make myself accessible to the governors and be helpful to the states. I don't foresee a future in politics right now or serving in any kind of government capacity for myself. I really don't. But I'm available. I pick up the phone, I call people back, and I try to be helpful to whoever I can.

MORE Q&As: Coronavirus experts on what to do and U.S. response to the pandemic

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: COVID-19 vaccine: ‘Get as many shots in arms as possible, right away’